1 Introductory

Let me right at the beginning posit a problem: are we at all entitled to speak about Dravidian literatures (or even about South Indian literatures) as an entity separate from other literatures of India? In other words: is there a complex set of features which are characteristic for the literatures written in Dravidian languages and shared only by them and not by other Indian literatures?

The criteria, setting apart “Dravidian” literatures from the other literatures of India, are either linguistic or geopolitical.

“Dravidian literatures” means nothing more and nothing less than just literatures written in the formal style of the Dravidian languages, “South Indian literatures” means, by definition, literatures which originated and flourished in South India (including Sanskrit literary works, produced in the South).

The answer to this question whether there are some specific, unique features shared exclusively and contrastively by the literatures written in Dravidian languages is negative. There are no such features—apart from the incidental (for our purposes and from our point of view) fact that they are written in Dravidian languages. It is impossible to point out specific literary features of works composed, e.g., in classical Telugu, and designate them as Dravidian. It is equally impossible to select any particular feature which we could term Dravidian as such and would apply to all Dravidian literatures alike and only to them.

Conclusion: there are no “Dravidian” literatures per se.

It is, however, an entirely different matter if we consider carefully just one of the great literatures of the South: the Tamil literature. There, and only there, we are able to point out a whole complex set of features so to say a bundle of diagnostic isoglosses—separating this Dravidian literature not only from other Indian literatures but from other Dravidian literatures as well. It is of course only the earliest period of the Tamil literature which shows these unique features. But the early Tamil poetry was rather unique not only by virtue of the fact that some of its features were so unlike everything else in India, but by virtue of its literary excellence; those 26,350 lines of poetry promote Tamil to the rank of one of the great classical languages of the world—though the world at large only just about begins to realise it.

All other Dravidian literatures—with the exception of Tamilbegin by adopting a model—in subject—matter, themes, forms, in prosody, poetics, metaphors etc.—only the language is different; in spite of the attempts of some Indian scholars to prove that there were that there must have been—indigenous, “Dravidian”, pre-Aryan traditions, literary traditions, in the great languages of the South, it is extremely hard to find traces of these traditions, and such attempts are more speculative than strictly scientific. It is of course quite natural that in all these great languages oral literature preceded written literature, and there is an immense wealth of folk literature in all Dravidian literary as well as non-literary languages.

But in Telugu, Kannada, and Malayalam, the beginnings of written literatures are beyond any dispute so intimately connected with the Sanskrit models that the first literary output in these languages is, strictly speaking, imitative and derived, the first literary works in these languages being no doubt adaptations and/or straight translations of Sanskrit models. The process of Sanskritization, with all its implications, must have begun in these communities before any attempt was made among the Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam peoples to produce written literature, and probably even before great oral literature was composed.1 About Kannada, Telugu and Malayalam literatures we may say with K. A. Nilakanta Sastri (HSI, 3rd ed. p. 340): “All these literatures owed a great deal to Sanskrit, the magic wand of whose touch alone raised each of the Dravidian languages (but here I would most definitely add: with the exception of Tamil, K.Z.) from the level of a patois to that of a literary idiom”. Whoever has written so far on the history of Kannada, Telugu, and Malayalam literatures take refuge in a formulation which is characteristic for speculative conclusions; cf. “the beginnings of Kannada literature are not clearly traceable, but a considerable volume of prose and poetry must have come into existence before the date of Nṛpatunga’s Kavirājamārga (850 A.D.), the earliest extant work on rhetoric in Kannada”; or “beyond doubt there must have existed much unwritten literature (in Telugu) of popular character …….” etc. The facts are different.

1 Incidentally, a community which has totally escaped the type of diffusion that had been identified by the term “Sanskritization” (cf. the writings of M. N. Srinivas and Milton Singer for the introduction and elaboration of this term), at least in South India, has yet to be found. As M. B. Emeneau pointed out, one can enumerate a number of important traits even in such isolated groups as the Todas and Kotas of the Nilgiris, which may be called Sanskritic (even the Toda word töw “god” is ultimately derived from Sanskrit, cf. DBIA 219 Skt. daiva- “divine” > Pkt. devva- > Ka. devva, devvu “demon” whence probably To. töw; cf. “Toda Verbal Art and Sanskritization”, Journal of the Orient. Institute, Baroda, XVI, 3-4, March-June, 1965). What is important for our problem is that, according to Emeneau’s opinion, these Sanskritic traits in the Nilgiris are very old; they can hardly be considered as a recent acquirement.

The beginnings of Kannada literature were almost totally inspired by Jainism. The first extant work of narrative literature is Śivakōṭi’s Vaḍḍārādhane (cca 900 A.D.) on the lives of the Jaina saints. The fundamental work on rhetoric in Kannada, and the first theoretical treatise of Kannada culture, is based on Dandin’s Kāvyādarśa—that is Nṛpatunga’s Kavirājamārga. Pampa, the first great poet of Kannada literature—and one who is traditionally considered the most eminent among Kannada classical poets—is, again, indebted entirely to Sanskrit and Prakrit sources in his two compositions, in his version of the Mahābhārata story, and in his Ādipurāṇa, dealing with the life of the first Jaina Tīrthankara. The beginnings of Kannada literature are, thus, anchored firmly in traditions which were originally alien to non-Aryan South India. Quite the same is true of Telugu literature. Telugu literature as we know it begins with Nannaya’s translation of the Mahābhārata (11th Cent.). The vocabulary of Nannaya is completely dominated by Sanskrit. And again: the first theoretical work in Telugu culture, fragments of which have recently been discovered, Janāśrayachandas, an early work on prosody, is itself written in a language which is more Sanskrit than Telugu; it contains traces of metres peculiar to Telugu and unknown to Sanskrit, and only this fact indicates that there had probably existed some compositions previous to the overwhelming impact of Sanskritization. In Malayalam, too, the beginnings of literature are essentially and intrinsically connected with high Sanskrit literature: the Uṇṇunīli Sandēśam, an anonymous poem of the 14th Century, is based on the models of sandeśa or dūta poems (the best known representative of which is Kālidāsa’s Meghadūta); its very language is a true maṇipravāḷam which is defined, in the earliest Malayalam grammar (the Līlātilakam of the 15th Cent.), as bhāṣāsamskṛtayogam, i.e. the union of bhāṣā (the indigenous language, Malayalam) and Sanskrit.

An entirely different situation prevails in Tamil literature. The earliest literature in Tamil is a model unto itself—it is absolutely unique in the sense that, in subject-matter, thought-content, language and form, it is entirely and fully indigenous, that is, Tamil, or, if we want (though I dislike this term when talking about literature), Dravidian. And not only that: it is only the Tamil culture that has produced—uniquely so in India—an independent, indigenous literary theory of a very high standard, including metrics and prosody, poetics and rhetoric.

There is yet another important difference between Tamil and other Dravidian literary languages: the metalanguage of Tamil has always been Tamil, never Sanskrit. As A. K. Ramanujan says (in Language and Modernization, p. 31): “In most Indian languages, the technical gobbledygook is Sanskrit; in Tamil, the gobbledygook is ultra-Tamil”.2

2 This may be illustrated by comparisons of grammatical or philosophical terms. In Telugu, e.g., the gender categories of “higher” and “lower” classes are termed mahat: amahat ( < Sanskrit); in Tamil, the corresponding terms are uyar-tiņai and ahṟiṇai (< al tiṇai), which is pure Tamil. Most Indian languages use for “vowel” and “consonant” the Sanskrit terms svara and vyañjana; in Tamil, the terms uyir (Ta. “breath”) and mey (Ta. “body”) have always been used (with the exception of a rather “pro-Sanskrit”, “Aryan-oriented” Buddhist grammar Viracōḻiyam which introduced Sanskritized grammatical terminology into Tamil; but the usage has not spread at all). Even such philosophical terms as “meaning”, “form”, “soul”, karma etc., have always been preferably expressed in “pure” Tamil, cf. resp. poruḷ DED 3711, uru DED 566, uyir DED 554, viṉai or ūḻ DED 4473, 2258.

There is an obvious historical explanation of the fact: the earliest vigorous bloom of Tamil culture began before the Sanskritization of the South could have had any strong impact on Tamil society. It is now an admitted fact by scholars in historical Dravidian linguistics that the Proto-South Dravidian linguistic unity disintegrated sometime between the 8th-6th Cent. B.C., and it seems that Tamil began to be cultivated as a literary language sometime about the 4th or 3rd Cent. B.C. During this period, the development began of pre-literary Tamil (a stage of the development in the history of the language which may be rather precisely characterised by important and diagnostic phonological changes) into the next stage, Old Tamil, the first recorded stage of any Dravidian language. The final stages of the Tamil-Kannada split, and the beginnings of ancient Tamil literature, were accompanied by conscious efforts of grammarians and a body of bardic poets to set up a kind of norm, a literary standard, which was called ceyyuḷ—or the refined, poetic language or alternatively centamiḻ—the elegant, polished, high Tamil. The final outcome of these events—the creation of a literature of very high standard and of a rich and refined linguistic medium—found expression in the excellent descriptive grammar Tolkāppiyam, one of the most brilliant achievements of human intellect in India.

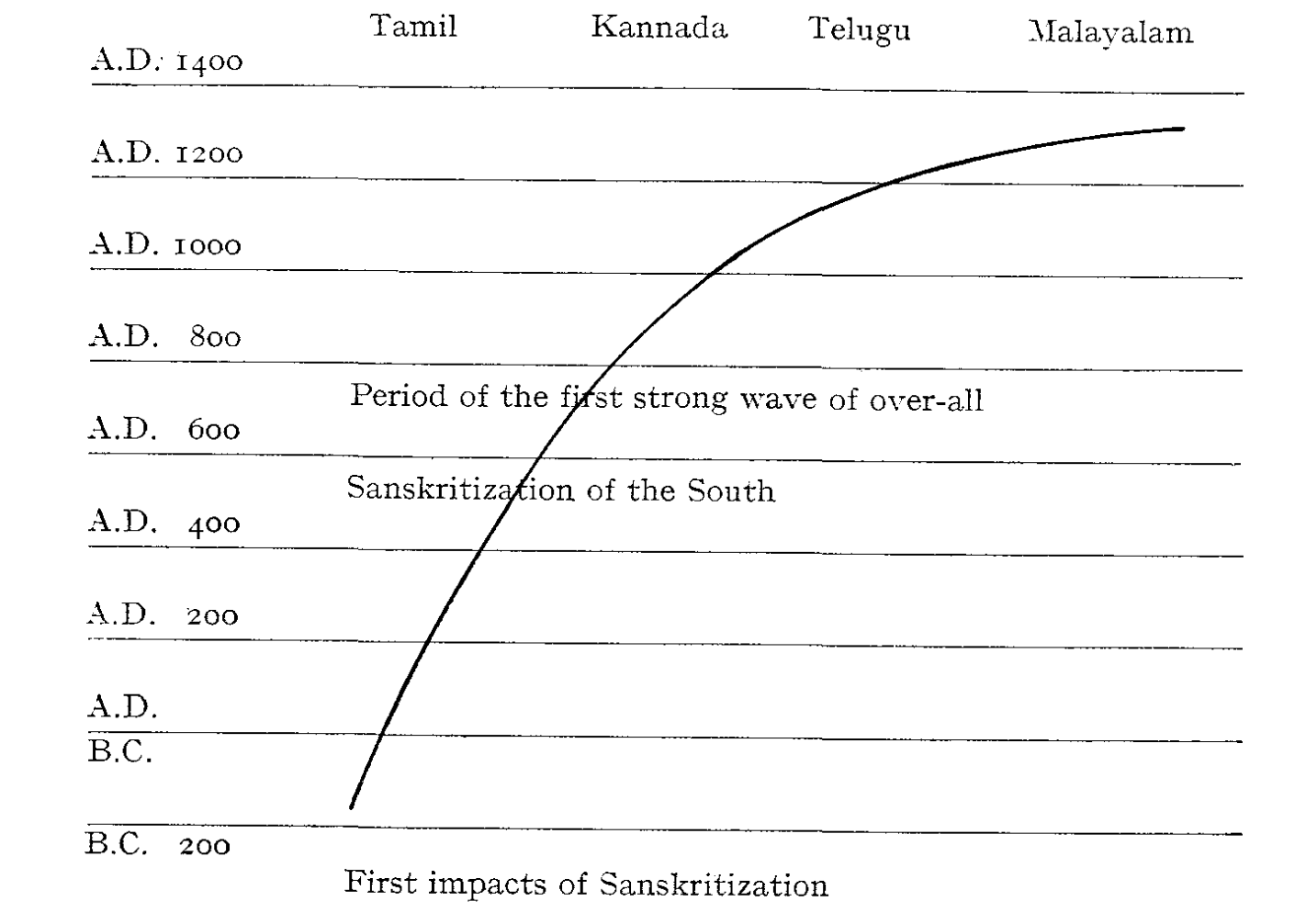

Table 1.1 and Figure 1.1 give the data for the first extant literary works and epigraphic monuments of the four South Indian languages, and a kind of graph which shows a sharply rising curve indicating the tremendous time-gap between the beginnings of Tamil written literature on the one hand, and the other Dravidian literatures on the other hand. These data are self-explanatory and need no commentary.

The influence which the various South Indian literatures exercised on one another was, at certain periods, not inconsiderable: thus, e.g., a certain very early school of Malayalam poetry was obviously strongly influenced by Tamil; or, to quote another example, Kampaṉ’s Tamil Rāmāyaṇa seems to have had an influence on some other South Indian Rāmāyaṇas. On the other hand, this mutual interaction has never been decisive or even very important. Apart from the earliest period of the development of Malayalam literature, South Indian literatures seem to have developed more or less independently of each other. There was one very good and simple reason for this: the one language which was almost equally spread over the South Indian territory as the language of highest learning and culture was Sanskrit. The intellectual exchange very probably took place through the medium of Sanskrit and the Prakrits; Sanskrit literature composed in the South was of a very high quality and of a considerable volume.

A fact which tends to be overlooked: so many outstanding Sanskrit authors were Southerners-Tamil, Kanarese or Kerala Brahmins, who in many cases could not help but let themselves be enriched and influenced by indigeneous traditions, conventions etc. A typical case is that of the great Rāmānuja, the founder of the Viśiṣṭādvaita system. Though an exact and final proof of a direct connection between the Tamil Vaiṣṇava Āḻvārs and Śrī Rāmānuja is yet to be submitted, there is more than ample external evidence to show that the traditions and the emotional and intellectual background of Śrī Rāmānuja were identical with the environments which produced the great Tamil Vaiṣṇava Āḻvārs. Rāmānuja was a Tamil Brahmin born at Śrīperumpūtūr near Madras in 1018, and had his early philosophical training at Kāñcipuram, but built up his philosophy of qualified monism in Śrīraṅkam, and travelled throughout India to propagate his ideas. The important fact is that Rāmānuja followed, in the evolvement of his philosophy, Yamunācārya (b. 917) who was the grandson of Ranganāthamuni (824-924), the first of the great Ācāryas of Vaiṣṇavism who followed directly the Tamil Āḻvārs; Ranganāthamuni actually became the final redactor of the Vaiṣṇava Tamil canon; and the grandson and direct spiritual inheritor of this man, Yamunācārya, who also went under his Tamil name Āḷavantār, became the guru of Rāmānuja. Thus, a direct and uninterrupted line leads back from Rāmānuja to the greatest of Āḻvārs and one of the greatest Tamil poets, Nammāḻvār, who was the guru of Ranganāthamuni.

Without going into details, it is proper at least to mention by name the most important Sanskrit poets, commentators, philosophers and Sanskrit literary works, intimately connected with the South. It is well-known that, under the patronage of early Vijayanagara kings, notably Bukka I, a large body of scholars headed by Sāyaṇa undertook and completed the enormous task of producing a commentary upon the Saṃhitās of all the four Vedas, and many of the Brāhmaṇas and Āraṇyakas.

It is not always stressed, however, that the Bhāvagatapurāṇa was composed somewhere in South India about the beginning of the 10th Cent., and that it summed up the outlooks and beliefs of typical South Indian bhakti; it is a fact that the Bhāgavatapurāṇa combines a simple emotional bhakti to Kṛṣṇa with the advaita of Śaṅkara in a manner that (to quote K. A. Nilakanta Sastri) “has been considered possible only in the Tamil country of that period”. Among the most interesting dramatic compositions coming from the Tamil South are the two unique farces (prahasanas), Mattavilāsa and Bhagavadajjuka, written by that immensely attractive figure in South Indian history, the “curious-minded” Mahendravarman the First of Kāñci.

In the domain of Vedānta, all the three major schools had their origin in the South: Śaṅkara (born in 788 at Kaladi in North Travancore) was a Kerala Brahmin. One may go on enumerating hundreds of Sanskrit works in the field of belles-lettres, rhetoric, grammar, lexicography, commentatorial literature, philosophy etc., all of them written in the South. This we will not do, naturally; it is important, however, to appreciate the fact that Sanskrit literary works are an integral and intrinsic part of the literary heritage of the South and that Sanskrit was the language of learning and higher culture throughout South India, though, of course, to a different degree in different parts of the South, and in different periods.

| Tamil | Kannada | Telugu | Malayalam | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| inscriptions | literature | inscriptions | literature | inscriptions | literature | inscriptions | literature |

| Early Tamil Brāhmī (“Damilī”) inscriptions, 3.-1. Cent. B.C. (Aśokan / 272-232 B.C. / Brāhmī introduced ca. 250 B.C. into the Tamil country and adapted between 250-200 B.C. to Tamil |

|

ca. 450 A.D. | beginnings in the 6.-7. Cent. A.D. (lost), Nṛpatunga’s Kavirājamārga (ca. 850 A.D.) | 633 A.D. | beginnings in the 7.-9. Cent. (lost), Nannaya’s translation Mahābhārata (11. Cent.) | Close of 9. Cent. (Kōṭṭayam plates of Sthāṇu Ravi), Chokur inscriptions ca. 925 A.D. | Rāmacaritam of Cīrāman Tamil literature Unnunili Sandēśam (anonym.), (14. Cent.) |