7 Themes, Motives, Formulae

K. Kailasapathy has shown, in his excellent book Tamil Heroic Poetry (1968), that the most important structural element in the Tamil classical (heroic and erotic) poem was the formula.1 The oral bard, reciting his themes, had to work rather fast in the midst of an enthusiastic, thrilled and demanding audience; he could hardly hold his audience in permanent attention. That is why the formulae had so great functional value for both the audience and the minstrels (Kailasapathy, op. cit. p. 138).

1 A recurrent element in narration or description, restricted by metrical considerations, as a rule an exact repetition “of a group of words expressing a given essential idea” (K. Kailasapathy, M. Parry).

Kailasapathy quotes a number of formulae occurring again and again in the classical corpus of the poems, e.g. naṉantalai yulakam (metric pattern = = / = -) “wide-placed world”, cf. Puṟ. 221.11; Patiṟ. 63. 18, Kalit. 6.3, Mullaip. 1; or ciṟukaṇyāṉai “the small-eyed elephant” (metric pattern = - / - -), occurring in Ak. 314.3, 327.2, 24.13, 179.4, Naṟ. 232. 1, Puṟ. 6.13, 316.12, 395.18 etc.

Some formulae show absolutely identical structure and exponents, save for one “synonym” used for another, like in aravu vekuṇṭaṉṉa tēṟal (Pur. 376.14): pāmpu vekuṇṭaṉṉa tēṟal (Cirupāṇ. 237) “toddy that stupefies like (poison of) the snake”.

Apart from such formulae, occurring in the midst of the text, there are many set beginnings and endings of poems, e.g. “I laugh whenever I think of it” (Naṟ. 110.1, 107.1) or amma vāḻi tōḻi “Listen, o friend” (Kuṟ. 77.1, 134.1, 146.1 etc.).

To Kailasapathy’s rich material, contained on pp. 147-170 of his book, I should like to add the following akam examples based on one collection of poems, the Kuṟuntokai (to show that Kailasapathy’s conclusions concerning the occurrence and function of formulae in Tamil bardic poetry are generally valid for the whole corpus, for the erotic genre as well as for the heroic). The formulae can be just simple attribute-head constructions, like e.g. val vil “mighty bow”, in Kuṟ. 100.5, Aiṅk. 373.5, 390.3, Kalit. 7.6, 104.58, Ak. 120.12, 152.15, 281.5, Puṟ. 150.7, 152.6 etc., or karuṅkāl vēṅkai “black-stemmed vēṅkai”, in Kuṟ. 26.1, 47.1, 343.5, Naṟ. 151.8-9, 168.1, 257.5, Aiṅk. 219.1, or taḻaiyaṇi yalkul “the venus’ mound, adorned by leaf-garment” in Kuṟ. 172.2, 195.2, 391.6, cf. Tolk. Kaḷavu 23, Nacciṉārk. comm., or neṭu meṉ paṇait tōḷ “large, soft, broad shoulders” in Kuṟ. 185.2, 268.6.

Quite frequently such simple formulae reappear in slight variation: either the order of the words is changed, or the exponents are substituted for each other, cf. aruvikaṉ mukai (Kuṟ. 95.1-2), lit. “waterfall(s)—rock(s)—cave”: kaṉmukai aruvi (Pur. 147.1), lit. “rock(s)—cave(s)—waterfall(s)”.

More or less elaborate similes enter very often into the stock of the formulae, like pūppōluṇkaṇ “darkened eyes similar to blossoms” in Kuṟ. 101.4, Naṟ. 20.6, 325.7, Aiṅk. 16.4, 101.4, Mullaip. 23, cf. malarēruṅkaṉ “id.” in Kuṟ. 377.1. This utterance actually forms the first half of a verse (Kuṟ. 101.4) which is composed of a double formula (the prosodic shape of the line is — — / — — // — — / — — ): pūppōluṇkaṇ poṉpōṉmēṉi; the second formula, which means “gold-like figure”, reappears in Kuṟ. 319.6 (poṉṉēr mēṉi) and in Naṟ. 10.2, Aiṅk. 230.4, Ak. 212.1-2.

The fact that the formulae are often metrically equivalent means that they are structurally interchangeable. Thus e.g. a formula like uḷḷi ṉuḷḷam vēmē (Kuṟ. 102.1) “when (I) think (on it, my) heart burns”, can be readily substituted for uḷḷi nuṇṇōy malkum (Kuṟ. 150.4) when (I) think (on it), the heart-ache grows”: both have identical prosodic pattern ( — — / — — / — — ).

The substitution of larger or smaller portions, or of entire formulae, and the variation which thus arises, play an all-important role in the bard’s skill of improvisation.

K. Kailasapathy quotes a number of such cases; some formulae show absolutely identical structure and exponents save for one synonym used for another, like in Kailasapathy’s quoted example Puṟ. 376.14: Ciṟupāṇ. 237; cf. a similar case from my material: pacu veṇ ṭiṅkaḷ (Kuṟ. 129.4): pacu veṇ ṇilavu (ib. 359.2, Naṟ. 196.2) “young/green/white moon”.

Sometimes, though, the underlying formula is changed to such an extent that we should rather talk of variation, as in Kailasapathy’s examples “the ships come with gold and return with pepper” (Ak. 149.10) and “the waves come with shrimps and recede with garlands” (Ak. 123.12).

A formula may sometimes be followed through whole centuries of literary texts of this nature is, for instance, a beautiful metaphor which has its origin probably in Kuṟuntokai 91.5: māri vaṇ kai “the strong hand of the monsoon-rain” may be recognized in Ciṟupāṇ. 124 peyaṉ maḻait taṭak kai “the strong hand of the great rain”, in Maturaik. 442 (vāṉa vaṇ kai), in citations in commentaries (Tolk. Uvam. 11 and 14, Pērāciriyar’s comm., cf. also Puṟ. 54.6-7), and even in such medieval texts like Cīvakacintāmaṇi 2779 (maḻai taḻīiya kaiyāy). Or, the formula uḷḷi ṉuḷḷam vēmē (Kuṟ. 102.1, and elsewhere) reappears in Tirukkuṟaḷ 1207 uḷḷiņu muḷḷañ cuṭum and much later in Kampaṇ’s Rām. Tāṭakaip. 5 (karutin vēm uḷḷamum).

Some of the formulae seem to be echoes of colloquial utterances, like yāṉ evaṉ ceykō “what should I do?” (Kuṟ. 25.2, 96.2, Aiṅk. 154.4) or utukkāṇ “there, look” (Kuṟ. 191.1, 81.11. Aiṅk. 101, 453, Kalit. 108.39, Puṟ. 307.3). The utterance uḷḷin uḷḷam vēmē (Kuṟ. 102.1 etc.) may probably also be regarded as a colloquialism.

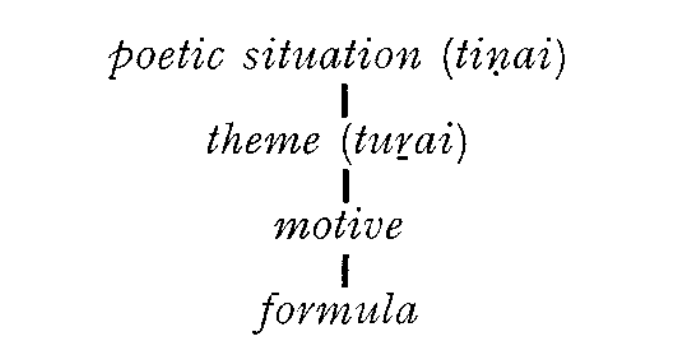

Apart from purely formal structural properties (metrical pattern, other patterned prosodical features like alliteration, “rhyme” etc.), every stanza is hierarchically organized in terms of form-meaning composites. This hierarchy may be set up as follows:

The basic and least inclusive element in this structure is the formula (in its shortest shape composed of two exponents, e.g. valvil, an Attribute-Head construction, “strong bow”), the most inclusive (since it encloses the whole stanza) is the tiṇai or poetic situation (there are hundreds and hundreds of formulae but only fourteen basic poetic situations accord. to Tolk. Poruḷ.). To quote an instance: in Kuṟ. 190, the poetic situation (tiṇai) can be characterized as mullai “separation and patient waiting”, mixed with kuṟiñci “desire”. Next in the hierarchy comes the theme (tuṟai) (also enclosing the entire stanza; but, under each tiṇai there are several decades of themes)2 which is, in our particular instance, “what the heroine, unable to bear separation, said to her girl-friend”. On the next lower level, there are several motives, e.g. the motive of the snake and the thunder, occurring quite frequently (thunderstorm as destroyer of snakes), e.g. in Kuṟ. 158.1-2, Patiṟ. 51.25-28, Ak. 92.11, 323.10-11, Puṟ. 17.38-9, 37.1-4, 58.6-7. 126.19, 366.3. The motives are different from the formulae; motives are recurring reflexes of experience, not necessarily clad in identical or nearly identical linguistic material. Formulae, on the other hand, are structures which apart from a full or almost full semantic identity show a high degree of formal identity (including prosodic structure), such as, in our particular example, neṟiyiruṅkatuppu “tightened black tresses” which reappears in Ak. 35.17 and 269.2 in identical structure and exponents, and in Kuṟ. 199.4. in the variation neripaṭukūntal “tightly combed hair”. A motive is as a rule more expanded and more inclusive than the formula: thus, e.g., it is a recurrent theme in both heroic and love poetry to describe the flourishing sea-port of Toṇṭi (known well to Graeco-Roman sources as Tyndis); this theme “occurs at least twenty-two times in the Anthology poems” (Kailasapathy, op. cit. 212). It is a recurring motive in the love poems to compare Toṇṭi with the heroine (Ak. 171.4, 173.3-4. 174.1-2, 175.4, 176.1-3, 177.4, 180.4, 60.7-8). The descriptions of Toņṭi are often recurrent formulae, e.g. “Tonṭi of seaside groves” (Pur. 48.4, Naṟ. 18.4, 195.5).

2 Thus, e.g. under the puṟam poetic situation called veṭci “cattle-raid”, there come 14 themes, according to TP. According to PVM, the 13 “heroic” situations comprise as many as 327 themes (see K. Kailasapathy, op. cit. 194).

3 As Kailasapathy rightly observes, “the itinerant life of the bards … spread the bardic language. The evolution of standard Tamil was an inevitable concomitant of bardic literature”.

These basic hierarchically structured components—the poetic situation, the theme, the motive and the formula—are parts of given traditional material; the bardic practice is dependent upon this traditional material. As already said, a tension arises between this traditional materia and the bard’s ability to improvise. The language of the poetry, is, too, stereotyped, conventionalized, traditional. Because of the traditional situations, themes, motives and formulae, and because of the language stereotype, there is an underlying unity of though-content, diction, style and form of the classical poetry.3

This brings us to the problem of the individuality of the poet, and of his originality; also, to the problem of imitation within the corpus. According to Tolkāppiyam and its commentator Iḷampūraṇar, in a good poem, unity should prevail among the details of a theme, and the theme itself should be in harmony with tradition. In these traditional and greatly stylized poems it is almost impossible to point out individual authorship. The problem of an independent, original creative personality is alien to the bard; the bard is, consciously, “effectively traditional” (Kailasapathy), exploring all potentialities of the tradition. Therefore, the question of imitation does not at all arise, as there is no question of plagiarism or copyright (Bowra, cited by Kailasapathy, op. cit. p. 185).4

4 Long before Kailasapathy made the theme and the formula subjects of an explicit analytic treatment, M. S. Purnalingam Pillai (in 1904) wrote: “The recurrence of certain ideas and images in some of these idyls by different authors bespeak the stock-in-trade and no literary theft. Broad streets are river-like, rice stalks finger-like, women’s soft soles the gasping dog’s tongue-like etc.”.

However, there are a few distinct and strong personalities of poets who have been acclaimed as the best among the bards. Paraṇar, Kapilar and Nakkīrar are probably the three classical Tamil poets who should be mentioned by name in this connection.

Paraṇar is the one of the great trio who is probably the least “original”. He is very disciplined and follows the conventions closely. However, some of his similes and metaphors are truly exquisite. Probably the most beautiful one is to be found in Kuṟ. 399, where the pallor of the beloved is compared to the persistent moss on the surface of a pool, which “with every thouch gives way / and spreads back with each estrangement”.5 It is significant that this picture is not part of any formula, and reappears only later in clear imitation (Kalit. 130.20-21).

5 uruṅ kēṇi yuṇṭuṟait tokka / pāci yaṟṟē pacalai kātalar / toṭuvuḻit toṭuvuḻi niṅki / vituvuḻi vituvuḻip paratta lāṉē.

The technique of suggestion was also exploited effectively by this great poet: when trying e.g. to describe the behaviour and character of a faithless lover he says:

“To eat the silver fish, the stork, as though

Afraid its steps were audible,

Moves soft—

burglar entering

A guarded house”

—

(Akam 276).

Nakkīrar is probably a stronger creative personality than Paraṇar. He is, above all, the author of one of the “Ten Lays”, the Neṭunalvāṭai, probably the best of them. In short lyrical poems, he seems to have preferred the pālai situation. He seems to have been “the most conscious craftsman”6 among the great poets of the classical age: cf. e.g. Kuṟ. 143 with the elaborate alliteration and assonance patterns, or the beautiful Kuṟ. 161 with a very intricate phonic structure (listen to the music in the opening lines of his Kuṟ. 368 melliya lōyē melliya lōyē “O you whose nature is so gentle”).

6 C. and H. Jesudasan, op. cit. 32.

The tradition is unanimous in regarding Kapilar as the greatest of all classical Tamil poets. He is represented in all anthologies, being the author of 206 songs. His puṟam pieces throw some interesting light on his life. His Kuṛiñcippāṭṭu was written to instruct an Aryan prince in Tamil poetic conventions and may be regarded as a model creation. A whole one fifth of Aiṅkuṟunūṟu is ascribed to him. In these poems we recognize in him a master of condensation and an original author of lovely images. Probably the most beautiful of his love-poems is Kuṟ. 25 (the one which begins with yārum illait tānē kaḷvaṉ):

“None else was there but he, the thief,

If he denies it, what shall I do?

Only a heron stood by,

its thin gold legs like millet-stalks

eyeing the āral-fish

in the gliding water

on the day

he took me”.

Kapilar’s interest and genius was concentrated on nature of the hills. His descriptions of nature and his comparisons and metaphors, apt and daring, have probably no match in the whole bardic corpus. Cf. Naṟ. 13: “the vēṅkai scatters its blossoms like sparks of fire flying in the smithy”. Or, from Ak. 292:

“A small stone

sped from the woodman’s catapult

shot like an arrow

scattering vēṅkai flowers,

and spilled the honey from the comb

before it reached

the sweet fruit of the jack”.

Another question, connected with the problem of linguistic and stylistic stereotype, is the problem of relative internal chronology within the earliest corpus. Is it at all possible to discern among different chronological strata within the early anthologies? It is basically true what Kailasapathy says on p. 47 of his book: “… to arrange them (the poems, K.Z.) in strict chronological order is to force on them a pattern of linear development which does not appear in the poems. The question of imitation is as incongruous as that of authorship in the context of an oral tradition”.

No detailed and exact chronological stratification has as yet been performed with regard to this corpus. However, the answer to the question posed above may be, very probably, in principle positive, though a great deal of the results would be based on rather speculative procedure.

First of all, we may exclude from the earliest corpus Kalittokai, Paripāṭal and Tirumurukāṟṟuppaṭai as compositions which are positively later in origin. Being left with the 15 remaining texts (6 Anthologies and 9 Lays) we may set up a few theoretical and methodological principles which can help us as guide-lines while investigating the corpus from the point of view of relative chronology:

Historical allusions within the poems themselves. The clustering of bardic songs round certain personages and certain events in their lives enables us to set up relative sequence of events, and, hence, relative sequence of texts about the events (though this inference is speculative and not too safe). The same is true about allusions concerning the lives of some of the poets. Thus e.g. it is very probable that the historical sequence of the three great poets mentioned above was Paraṇar—Kapilar—Nakkīrar (e.g. Nakkīrar mentions Kapilar as living in the past in Ak. 78). The historical or near-historical (or even quasi-historical) data receive, in some cases, corroboration from external sources (inscriptions and the like).

A great deal of speculation as to the chronological order of the poems may be based on formal criteria:

- The simpler the metre and other prosodic properties, the older the poem (since there exists undoubtedly a tendency of formal complexity to increase steadily with the passage of time);

- affinity with folk-songs and echoes of colloquial utterances may probably be also regarded as indications of relative antiquity;

- it is probable that a relative chronology of motives and formulae could be set up: within one and the same motive and formula, the movement is from a simpler to a more involved and complicated pattern.

- Language:

- in the development of linguistic forms, we may discern (though with difficulty) certain innovations vis-à-vis certain retentions;

- the more Aryan loanwords, the younger (later) the text;

- loanwords from Prakrit and Pali are very probably older than Sanskrit loanwords.

- There is a development in thought-content:

- poems showing traces of Jainism and Buddhism are probably earlier than poems showing Brahmanic influence;

- straightforward descriptions of fighting, mating, nature etc. are probably older than poems which bear traces or elements of reflection and philosophy;

- didactic and philosophical poems with an undertone of pessimism are probably rather late;

- certain situations and themes (like kāñci and vākai in the puṟam genre and kaikkiḷai and peruntiṇai in the akam genre) are probably later.

It might be worthwile to apply these general considerations to the earliest bardic corpus and try to establish a relative chronology of poems within the fifteen texts, however much speculative and slender they may seem.

Finally, a remark on the intelligibility of early classical Tamil poetry is probably not out of place here; the early classical poetry is not intelligible to a modern Tamil speaker without special training and study. Formal Tamil of today is more conservative than the informal style and hence closer to earlier Tamil. But even an educated modern Tamil reader does not understand early classical texts unless he has made a special study of them. As A. K. Ramanujan says (in The Interior Landscape, p. 98): “The development of verb and noun-endings, losses and gains in vocabulary, and the influence of other languages like Sanskrit and English have widened the distance between ancient and modern Tamil”. But, though the gap between ancient Tamil poetry and its modern Tamil reader is very wide indeed, it does not matter much; it is more important that—as any classical literature—Tamil classical poetry belongs to the great literary heritage of the whole world.