9 Tolkāppiyam

The Tolkāppiyam1 represents much more than just the most ancient Tamil grammar extant. It is not only one of the finest monuments of human intelligence and intellect preserved in the Indian tradition; it is also the first literary expression of the indigenous, pre-Aryan Indian civilization; it represents the essence and the summary of classical Tamil culture.

1 The name Tolkāppiyam is an attribute-head construction which means “ancient (tol) book (kāppiyam < Skt. kāvya-)”. However, this Indo-Aryan etymology (which is not absolutely water-proof) was unacceptable for some Tamil purists, and so we may read such curious statements as the following: “tol means ancient and ‘Kāppiyam’ means Kāppu iyaṉṟatu that which deals with protection. The main function of grammar is to protect the language from deterioration and the word kāppiyam…” etc. (vide J. M. Somasundaram Pillai, A History of Tamil Literature, 1967, p. 50). Whether the book gave the name to the author or vice-versa is a disputed question. The first alternative is of course the more plausible one. The attribute tol “ancient, old” (cf. DED 2899; the word occurs in the oldest literature, cf. Puṟam 24.21, 32.7, 91.7, 203.2 etc.) is used here with the connotation “aged, hoary, venerable”.

2 Unfortunately, there exists no full, critical and exact translation of this extraordinary work into English (or, for that matter, into any Western language). The present writer is engaged in translating the text in full including the seven commentaries now available. As far as the overall atmosphere and the general context of Tolkāppiyam is concerned, I can hardly add anything to what M. B. Emeneau says about “Hindu higher culture” in his paper “India and Linguistics”, Collected Papers, Annamalainagar (1967) 187-188: “Intellectual thoroughness and an urge toward ratiocination, intellection, and learned classification for their own sakes should surely be recognized as characteristic of the Hindu higher culture”.

For the evaluation of Indian linguistic thought, it is probably as important and crucial as the grammar which goes under the name of Pāṇini. To the field of general linguistics, it would add, if sufficiently known, some new important insights on a number of phonetic, etymological, morphological and syntactic problems.2

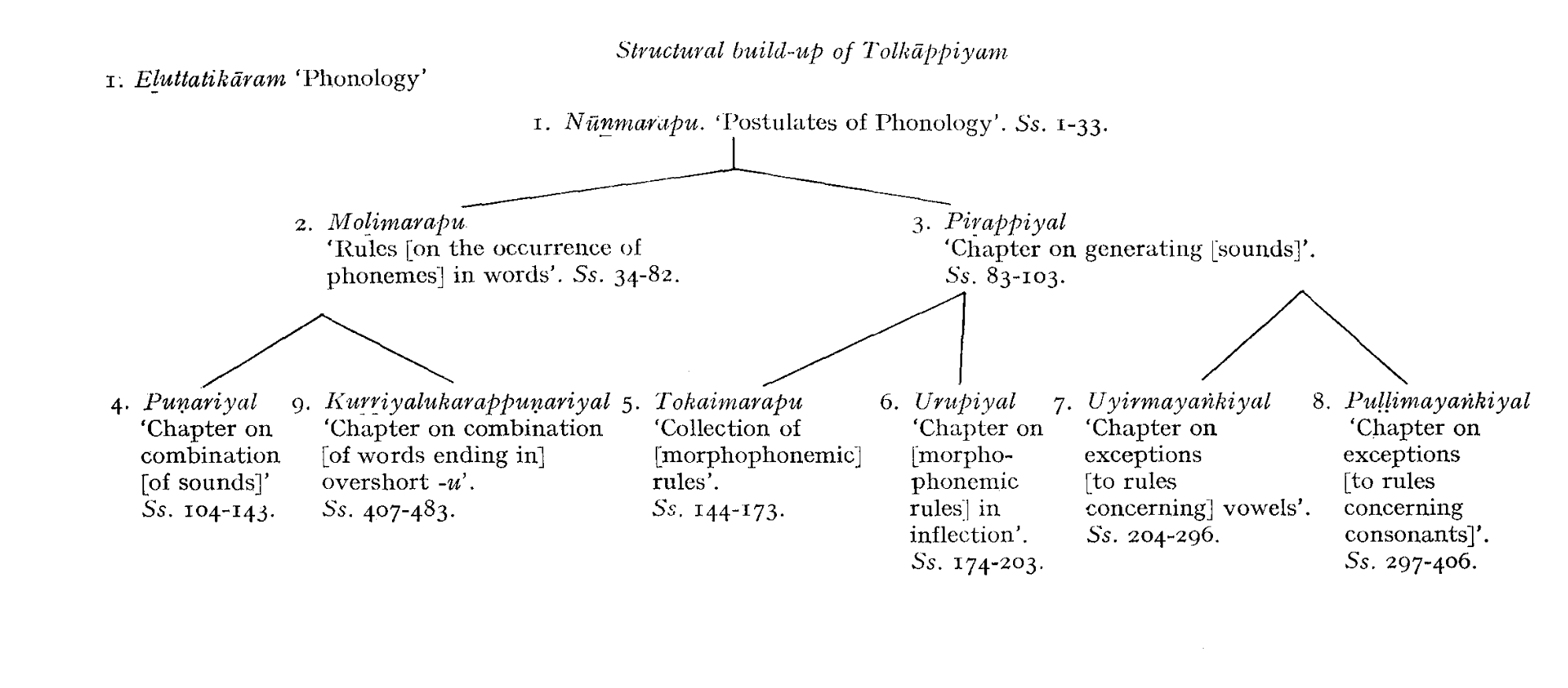

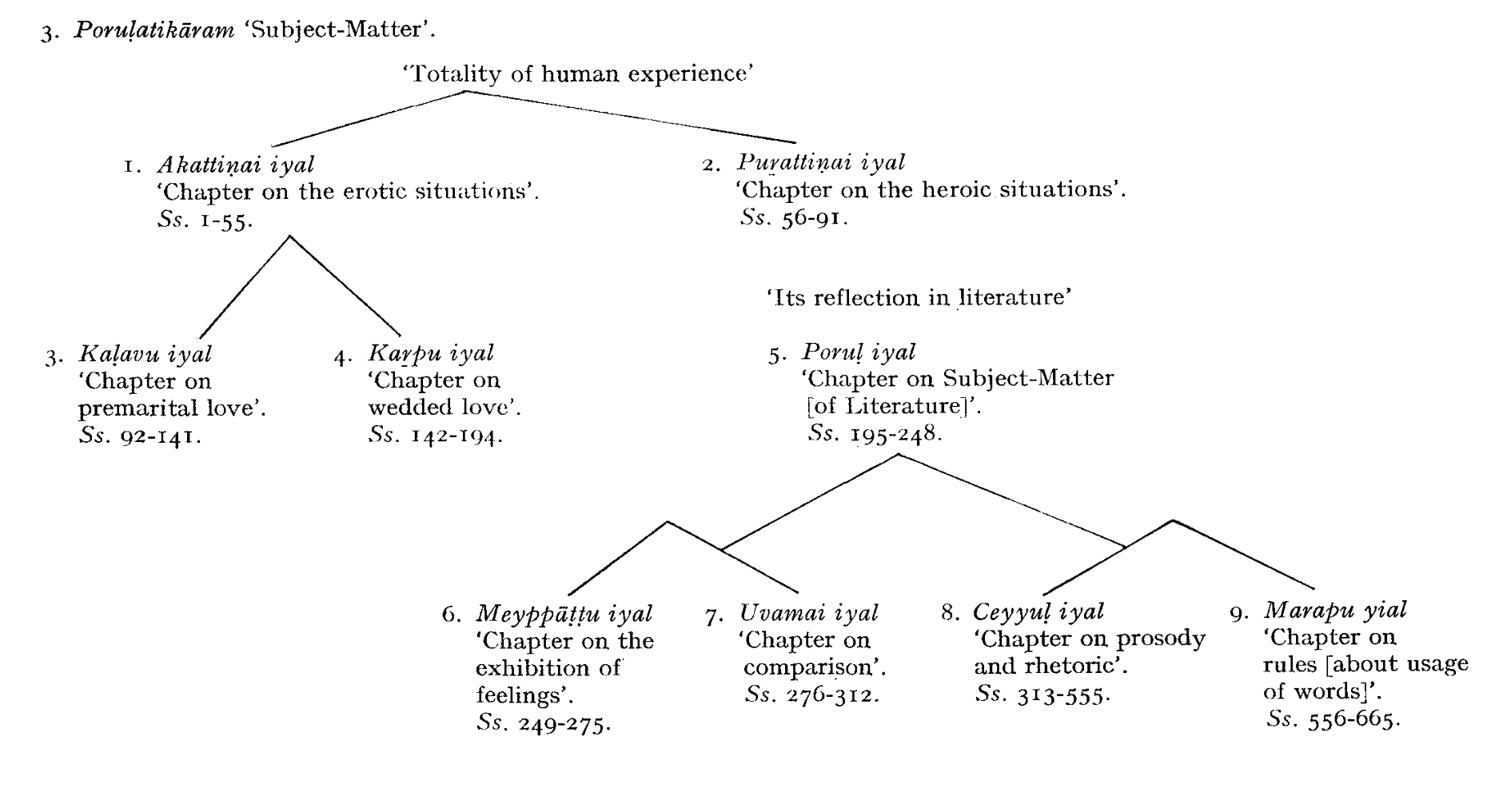

The Tolkāppiyam, as we have it today, consists of three books (atikāram). Each book has nine chapters (iyal), and the whole has 1612 sūtras3 of unequal length in 27 chapters.4

3 When we use the term sūtras here, it is not quite exact; the rules are actually composed in a metre which resembles the akaval and is called nūrpā (< nūl + pā “the stanza / appropriate for / eruditory literature”); it is functionally equivalent to the sūtra in Sanskrit culture. Tamil nūl, like Sanskr. sūtra-, means 1) “thread, string, cord”, 2) “rule”, 3) “book”, especially “book of rules”, “eruditory book”.

4 There are nūṟpās of one line only; but quite a number of stanzas have as many as 9 lines and more. Most nūṟpās in the grammar have 2-3 verses. There are “nūl stanzas” which have as many as 46 lines. Like the akaval, a nūṟpā is composed of 4 feet; but unlike akavalpā it may have only one or two lines, and some other properties, which make it a different metre altogether.

Roughly speaking, the grammar deals with orthography and phonology, etymology and morphology, semantics, sentence structure, prosody, and with the subject-matter of literature.

In the nine chapters of the first section, Tolkāppiyam deals with the sounds of the language and their production, with combination of sounds (puṇarcci, “joining, copulation”), with orthography, and with some questions which we would today designate as graphemic and phonological problems. One may say that the first book “on eḻuttu” (this term may mean, in various contexts, “sound”, “phoneme” or “letter”) is dedicated to phonetics, phonology and graphemics of Old Literary Tamil. The treatment of the arrangement of consonants, and the description of the production of sounds is interesting.5

5 Highly interesting is the metaphor describing vowels as uyir “life, lifebreath”, consonants as mey “body” and the group consonant + vowel, in other words, the “most primitive”, open syllable, the basic unit of the syllabic script, as uyirmey “life-endowed body”. There is a number of other engaging problems, concerning, e.g., the āytam, or the sandhi, but a discussion of these questions is indeed beyond the scope and purpose of this book.

6 These paṉṉiru nilam or “twelve regions” were the source of “dialectisms” (ticaiccol, ticai < prob. Skt. diśā, instr. of diś “region, place”). The author or authors of Tolkāppiyam do not describe the dialectal regions in detail. The medieval commentators, though, tell us the names of the twelve regions, and denote the dialects by a common term, koṭuntamiḻ, lit. “crude, vulgar Tamil”. Also, the author of the prefatory stanza to the grammar was well aware of the stylistic distinction: he speaks, as of two distinct styles of one language, of vaḻakku “spoken, colloquial (style)” and ceyyuḷ “poetic, literary (style)”.

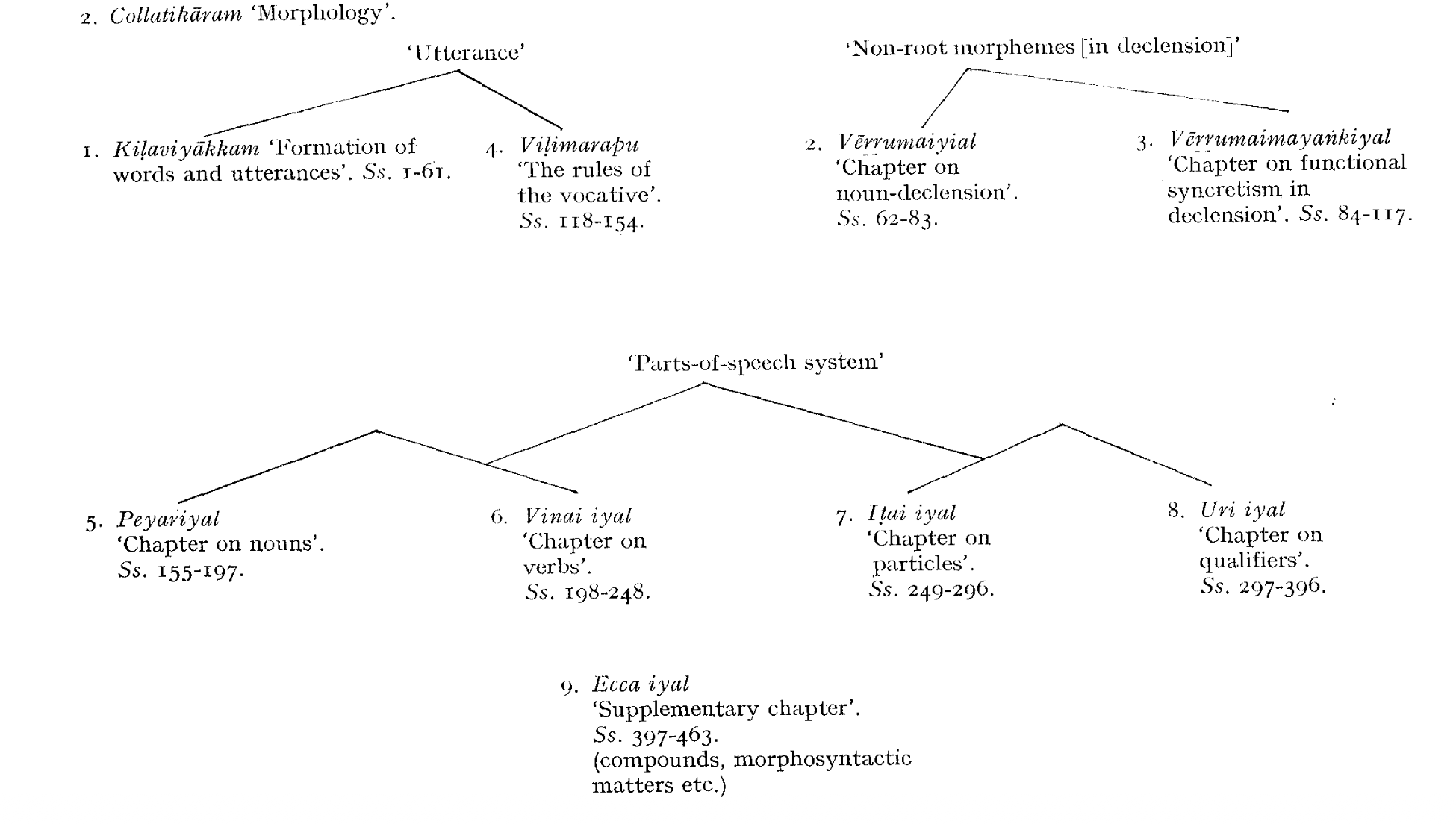

The second section is called Collatikāram, “The book about words”, and deals with etymology, morphology, semantics and syntax. Among the exciting problems emerging from the study of this book are questions of word-classes, of compounds, semantic problems, and rich lexical data. The author (or authors) had also some idea about linguistic geography of the Tamil land: standard Tamil was spoken in the centamiḻ land, and adjoining this area were the twelve dialectal regions.6

Poruḷatikāram, or the book dealing with “subject-matter” is, in short, the prosody and rhetoric of classical Tamil. In addition, it contains a wealth of sociological and cultural material.

The first two chapters of this atikāram (the akattiṇai iyal and the puṟattiiṇai iyal) contain a detailed treatment of literary conventions of both basic genres of classical literature, akam and puṟam. The next two iyals deal with the two kinds of love, pre-marital (kaḷavu) and marital (kaṟpu) and with extramarital relations, and in the subsequent parts, prosody (yāppu) and rhetoric (aṇi) are treated in detail.

The whole book on poetics is planned as follows:

- Treating of mutual love.

- Treating of war and non-love themes.

- Treating of secret or premarital love.

- Dealing with open wedded love.

- Treating of further aspects of love situations.

- Dealing with dramaturgy.

- Dealing with simile.

- Dealing with prosody and the art of composition.

- Treating of tradition and literary usage.

It may be seen from this outline, that the work, and, in particular, its third book, grew around a core which was intended as a bardic grammar, as a guide to bards as to how to compose their songs in accord with tradition and conventions.7

7 Cf. K. Kailasapathy, Tamil Heroic Poetry (1968) 48 ff.

8 “Grammar”, ilakkaṇam (< Skt. lakṣaṇa-) has a very broad sense here. The semantic field of the term ilakkaṇam comprises the nucleus, which is “prescriptive rules about the use of (literary) language”, further “description of the structure and function of the (literary) language”, and still further “description of the structure and functioning of any cultural phenomenon”. In this sense, one speaks of “the grammar of dance” as well as of “the grammar of war-poetry”. Ultimately, ilakkaṇam means treatment of the structure and function of any structured and conventionalized phenomenon: in this broadest sense, one speaks about “the grammar of love” (the patterned and conventionalized “reality” underlying love-poetry) or “the grammar of bhakti”.

In traditional terms, Tolkāppiyam deals with the total subject-matter of grammar (ilakkaṇam)8; with eḻuttu (basic “signs” of language; sounds and letters), col (“words”), poruḷ (subject-matter of poetry), yāppu (“prosody”), and aṇi (“rhetoric”).

No wonder that the grammar became enormously influential in the entire subsequent development of Tamil culture; its authority goes unquestioned to the present day.

Tolkāppiyam obviously contemplates a literature very much like that of the early classical (Caṅkam) age. However, it also gives a picture of an earlier literature. There are, according to the “ancient book”, two basic kinds of compositions: one which is governed by restrictions concerning lines and metres, the other which has no restrictions.9 The grammar seems to suggest also the existence of narrative poems.10 In these literary forms, six kinds of metres were employed: veṇpā, āciriyam, kali, vañci, maruḷ and paripāṭal.11

9 Tolk. Poruḷ. 476.

10 Tolk. Poruḷ. 549-553.

11 Tolk. Poruḷ. 433, 450, 472.

Under the second type (compositions with no line restrictions), the grammar quotes grammatical treatises, commentaries on grammars, compositions intermixed with prose, fables, humourous hits, riddles, proverbs, magical incantations and “suggestive imaginative statements”. It is obvious that much literature must have existed before the time of Tolkāppiyam, as we have it, and that the author(s) of the grammar made use of earlier grammatical works.

As a single integrated work, the Tolkāppiyam was first mentioned in Nakkīrar’s commentary on Iṟaiyaṉār’s Akapporuḷ (prob. 7th-8th Cent. A.D.).

Some of the nūṟpās are ambiguous. Also, as already stressed, the authority of Tolkāppiyam has always been supreme. These facts lead to the existence of a number of commentaries on the “grammar of grammars”, of which at least seven have been (partly) preserved.

The first, and probably the best commentary is that of Iḷampūraṇar. He fully deserves the title of uraiyāciriyar, i.e. “The Commentator”. His commentary has fortunately reached us in full. He was probably a Jaina scholar, living in the 11th or 12th Cent.

Iḷampūraṇar’s commentary shows a great deal of common sense and critical acumen. He obviously distrusted the tales connecting the mythical Akattiyar (Agastya) and the author of Tolkāppiyam. There might have been other, earlier, pre-Iḷampūraṇar commentaries in existence (probably in oral grammatical tradition, cf. Iḷampūraṇar’s hints to this in his comm. to Collatikāram 44, 57, 122, 421, 408, 68, 447 and elsewhere). One of the most pleasing features of Iḷampūraṇar’s commentary is its clear, simple, lucid prose, written in comparatively pure Tamil.

Cēṉāvaraiyar’s12 commentary pertains only to Collatikāram. His name occurs in several epigraphs, and it seems that the one which is dateable in 1275 A.D. has in mind our author.13 The commentary is detailed and precise, and very learned. It is interesting that its author contests the views of Pavaṇanti, and also questions some conclusions of Iḷampūraṇar.

12 Which means “general of the army”: cēnai (Skt. senā-) + araiyar (< Indo-Aryan rāya, rāa).

13 A place-name, Māṟōkkam, occurs both in the commentary and in the inscription. For the dating of Cēṉāvaraiyar in the reign of Māravarman Kulacēkara Pāṇṭiyaṉ (1268-1311) cf. M. Raghava Aiyangar, Cāsanat tamiḻ- kkavi caritam (Ramnad, 1947) 108-144.

- Pērāciriyar is heavily indebted to Naṉṉūl14 in his grammatical thought (besides quoting frequently from Taṇṭiyalaṅkāram and Yapparuṅkalam, the first being the standard medieval rhetoric, the second the most detailed treatise on prosody in Tamil). It seems that he wrote his commentary—of which only the portion pertaining to the greater part of Poruḷatikāram is available—sometime at the end of the 12th or rather in the 13th Cent., if not later.

14 According to tradition, Pavaṇanti composed his Naṉṉūl, the standard medieval grammar of literary Tamil, on the model of Ilampūraṇar’s commentary. Pavaṇanti lived in the first half of the 13th Cent.

Nacciṉārkkiṉiyar’s commentary is available to the whole text of the first and second book, and to five chapters of the third book of the grammar. He quotes the three previous commentators, often refuting their views. This great commentator, who was equally learned in Tamil and Sanskrit, quotes, too, in some of his commentaries, his famous colleague Parimēlaḻakar; and this shows that he lived probably in the 14th, if not in the 15th-16th Century.

Teyvaccilaiyār composed his commentary to the second book on col “word”. He is later than the four previously mentioned commentators. It seems that he was a learned Brahmin, very well versed in Sanskrit and in Aryan traditions. His date is probably the 16th Century A.D.

Kallāṭar seems to be the latest of the available commentators. His work refers to the second book only, to Collatikaram. He belongs very probably to the 16th-17th Cent. A.D.

Apart from the six commentaries, there is yet another anonymous commentary to the three chapters of Collatikāram,15 which seems to be more recent than any of the six commentaries mentioned above.16

15 To kiḷaviyākkam, vēṟṟumaiyiyal and veṟṟumaimayaṅkiyal.

16 The editors of an excellent and careful edition of Collatikāram, A. Arulappan and V. I. Subramoniam (Tirunelveli-Palayamkottai, 1963), designate this text as aracu (since they published it according to a manuscript obtained from the Aracāṅka nūl nilaiyam, “The Government Library”).

After this brief description of the text and the available commentaries, three rather tangled problems must be discussed: the person of the author, the date of the work, and its integrity.

In the commentary to the preface of the grammar, Nacciṉārkkiṉiyar identifies the author of the grammar with Tiraṇatūmākkiṉi, son of Camatakkiṉi, a Brahmin ṛṣi.17 The boy became one of the disciples of the sage Akattiyar (Agastya), and turned out to be a first-class grammarian. He wrote a grammar called Tolkāppiyam which, together with the work of his master, Akattiyam (now lost), is said to have been the grammar (nul) of the “second Caṅkam”.

17 These names are of course Aryan: Triṇadhūmāgni, son of Jamadagni, a ṛṣi mentioned in the Ṛgveda, in the Rāmāyaṇa and the Mahābhārata.

18 According to tradition (found fixed, e.g., in the prefatory stanza to Puṟapporuḷveṇpāmālai), Tolkāppiyaṉ and these fellow students of his were responsible for the production of another grammatical work, the Paṉṉirupaṭalam. This work on puṟapporuḷ is now lost but a few sūtras are preserved in Iḷampūraṇar’s comm. to Tolkāppiyam.

According to Pērāciriyar (ca. 1250-1300 A.D.), some scholars held that Tolkāppiyaṉār composed his work on principles other than those of Akattiyam, following some grammars no longer extant. The commentator refutes this theory and maintains that Akattiyaṉ was the founder of Tamil grammatical tradition, that Tolkāppiyaṉ was the most celebrated of the twelve pupils18 of the great sage and that he followed Agastya’s teachings in his own grammar. According to K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, the opposite party which denied Tolkāppiyaṉ’s indebtedness to Agastya “postulated hostility between teacher and pupil arising out of Agastya’s jealousy and hot temper”. The whole story is recorded by Nacciṉārkkiṉiyar. After Agastya left the Himalyas for the South, he sent his pupil Triṇadhūmāgni (Tolkāppiyaṉ) to fetch his wife Lopāmudrā from the North. He, however, prescribed a certain distance to be maintained between the pupil and the lady during the journey (“four rods”). While crossing the river Vaikai, a rapid current threatened to drown Lopāmudrā, and Tolkāppiyaṉ approached too close, holding out to her a bamboo stick with the aid of which she was able to reach the shore safely. This displeased the master and Agastya cursed them saying that they would never enter heaven; to which Tolkāppiyaṉ replied with a similar curse on his master.

As K. A. Nilakanta Sastri says, “this silly legend represents the last phase of a controversy, longstanding, significant, and by no means near its end even in our time”.19 However, the truth is that there is no mention of Agastya or Akattiyam in the Tolkāppiyam or in the preface to by Paṉampāraṉār. The earliest reference to the Akattiyam occurs only in the 8th or 9th Cent. A.D.

19 A History of South India (3rd ed., 1966) 77.

As we shall see later, Tolkāppiyam, the core of which may be assigned to the pre-Christian era, consists perhaps of many layers, some of which may be much earlier than others. We do not know of any definite data concerning the original author or authors. It seems that Tolkāppiyaṉ was a Jaina scholar, well versed in a pre-Pāṇinīan grammatical system called aintiram, and that he lived in Southern Kerala sometime in the 3rd-1st Cent. B.C.

A few data support the tradition which maintains that Tolkāppiyaṉ was a Jain. First, the pāyiram (preface) uses the term paṭimaiyōṉ which is derived from a Jaina Prakrit word and signifies a Jaina ascetic.20 There are further indications within the text corroborating this hypothesis: the classification of lives (jīva) and non-lives (ajīva) in Tolk. Marapiyal 27-33 appears to agree fully with the Jaina classification. The description of a mātrā (prosodic unit) as being equivalent in duration to kaṇṇimaittal “closing and opening of the eyelid” and to kainnoṭi “snapping of the finger” is supposedly of Jaina origin; the allusion to muṉṉitiṉ uṇarntōr (Eḻutt. 7) in connection with that description is obviously to Jaina ācāryas. According to the opinion of S. Vaiyapuri Pillai, Tolkāppiyaṉ belonged to a heterodox Jaina grammatical tradition called aintiram.21

20 Cf. S. Vaiyapuri Pillai, Tamiḻc cuṭar maṇikaḷ (3rd ed., 1959, p. 26), quoting Sinclair Stevenson’s The Heart of Jainism.

21 In the prefatory stanza, Paṇampāraṇār qualifies Tolkāppiyaṉ as aintiram niṟainta, i.e. “full of”, “well-versed in” aintiram.

22 The forms in question manifest a morph, -attu, e.g. paṉiyattu, maḻaiyattu, veyilattu, which does not occur with this distribution in literary Tamil of any period. S. Vaiyapuri quotes Malayalam utterances like paṉiyattu pōkarute, maḻaiyattu pōkarute. In Tamil, especially in Early Middle Tamil and subsequent stages, -attu occurs as a locative suffix with stems anding in -am in the nominative (this is an “impressionistic” statement). However, the extension of -a-ttu to other types of bases, like Malayalam teruvattu (cf. L. V. Ramaswami Aiyar, Evolution of Malayalam Morphology, 1936, 12) is definitely a Malayalam development, and a “Malayalamism” in Tamil.

23 There still exists a village by name of Ataṅkōṭu in South Travancore. The prefatory stanza says that the merits of the grammar were approved by Ataṅkōṭṭācāṉ (< ataṅkōṭṭu ācāṉ) i.e., “the teacher of Ataṅkōṭu”, a member of the learned assembly of king Nilantaru Tiruviṟ Pānṭiyan; who this Pāṇṭiyaṉ was we have no idea. The author of the prefatory stanza, Paṉampāraṉār, is probably identical with the grammarian whose work (Paṉampāraṉam) was preserved very fragmentarily in a few sūtras in the commentaries to Yāpparuṅkalam and Naṉṉūl.

As for his South Travancorian origin: It was again S. Vaiyapuri Pillai—probably the most critical of modern Tamil scholars—who has shown that Tolk. Eḻutt. 241, 287 and 378 quote grammatical forms which do not occur in literary Tamil texts, but which exist in Malayalam22. This fact supports the tradition which makes Tolkāppiyaṉ a native of Tiruvatāṅkōṭu in today’s Kerala.23

The problem of the dating of Tolkāppiyam is an extremely difficult one. It has to be attacked, though, since we would like to have at least an approximate chronology of the work which manifests the first conceptual framework and the earliest noetic system of a culture which is part of the world’s great classical civilizations.

The basic issues of this problem may be formulated as the following points:

- The relation of the language described in Tolkāppiyam (specifically in the Eḻuttatikāram), and of Tolkāppiyam’s metalanguage, to the graphemic and phonological system of the earliest Tamil inscriptions in Brāhmī.

- Is Tolkāppiyam earlier or later than the bulk of the “Caṅkam” poems? Is it a “pre-Caṅkam” or a “post-Caṅkam” work?

- The identity of the political and social background of the Tolkāppiyam and early Tamil classical poetry.

- The references (if any), in the Tolkāppiyam, to a. Patañjali, b. Pāṇini, c. Mānavadharmaśāstra, d. Kauṭilya’s Arthaśāstra, e. Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra, f. Kāmasūtra.

- Inconsistencies among the sūtras of the text.

Also, we have to start our investigation of this problem with a few presumptions, the most important of which are: 1) the existence of a body of literature24 before Tolkāppiyam, 2) relative (and an attempted absolute) chronology of the linguistic evolution of the earliest stages of Tamil.

24 Needless to say that by “literature” we do not necessarily mean “written literature”. Just as the term “text” does not necessarily mean anything written or recorded, so “literature” refers merely to a body of adopted, accepted compositions, which fulfil certain aestetic and social functions. The same when we speak about “literary” language of this early period: what we have in mind is a language different from the day-to-day colloquial, a language used in that body of compositions, a “higher” language which gained prestige and esteem (probably connected with its mantic usage), a language which would have had the function of literary language proper in a society with predominantly written (as against oral) cultural transmission.

25 With regard to the Tolkāppiyam, this fact was stressed long ago by Robert Caldwell: “Whatever antiquity may be attributed to the Tolkāppiyam, it must have been preceded by many centuries of literary culture. It lays down rules for different kinds of poetical compositions which must have been deduced from the examples furnished by the best authors whose works were then in existence” (quoted by B. Kannappa Mudaliyar, Tamiḻ nūl varalāṟu, 1962, p. 54). Tamil pandits have a saying which states the fact briefly and succintly: ilakkaṇattukku muṉ ilakkiyam “Before grammar—literature” (personal communication, S. Kokilam). In a more elegant form, the opinion that literature always precedes grammar, is expressed in the text of Akattiyam: ilakki yattiṉiṉ ṟeṭuppaṭu milakkaṇam “literature yields grammar”; cf. further Naṉṉūl s. 140: ilakkiyaṅ kaṇṭataṟ kilakkaṇa miyampal, “the utterance(s) of grammar are based on literature”. Tamil grammarians had also a clear conception of the principle of change in language; according to Tolk., usage sanctifies new words (kaṭico lillaik kālattuppaṭinē, Tolk. s. 935), and according to Naṉṉūl, it is in the order of things for the old to give place to the new: paḻaiyaṉa kaḻitalum putiyaṉa pukutalum / vaḻuvala kāla vakaiyi ṉāṉē (s. 461). We cannot but admire these insightful utterances of the ancient savants.

That some literature had existed before even the Urtext of the Tolkāppiyam was written is not only a reasonable assumption, but is supported by hints given in the text itself. As already mentioned, the grammar refers to earlier compositions of two basic types (e.g. Poruḷ. 476 et seq.) and from a great number of lines it is clear that earlier grammatical works have been made use of by Tolkāppiyaṉ (he constantly refers to his predecessors in grammar and learning with utterances like eṉmaṉar “they-honorific say”, eṉpa, collupa, moḻipa, “they say”: all this of course in the sense “it has been said, it is said” i.e. “it is the established scholarly tradition to say that…”). Before even the basic text of the grammar could at all have been composed, a period of development of a literary language (probably used in a body of bardic poetry) must have preceded the final stages of the standardization and normalization of early old Tamil. Never, in none but a very artificial situation, is literature preceded by grammar; it is always the other way round. First there is a body of texts, of literature (which, let me stress again, does not always mean written literature, recorded texts!), then a grammar.25

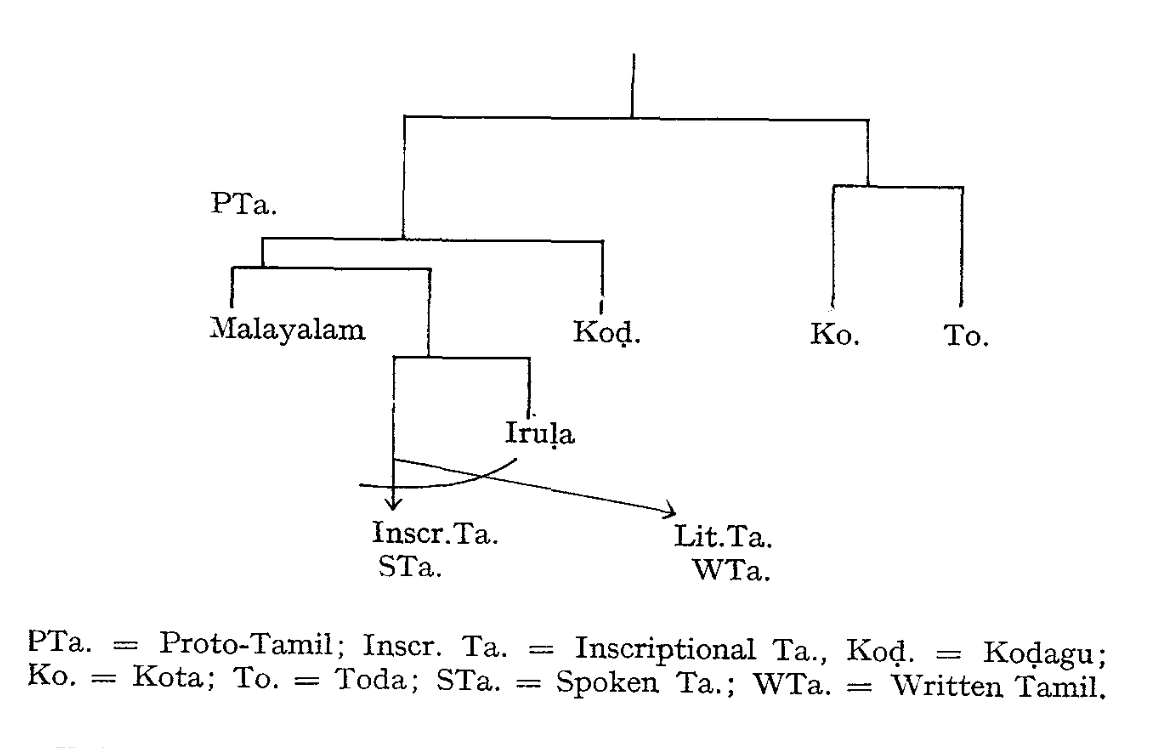

The linguistic situation in the extreme South of India, as it might have prevailed (simplified, of course, very considerably) sometime between the 4th-2nd Cent. B.C., can be represented by the following diagram:

This was probably the period when the first bardic poetry was composed in the Tamil language. About 250 B.C. or slightly later, Aśoka’s (272-232 B.C.) Southern Brāhmī script was adapted to the Tamil phonological system. And between 200-100 B.C., the earliest Tamil-Brāhmi inscriptions (about 50 in number) were produced by Jaina and/or Buddhist monks living in natural caves of the Southern country.26

26 I. Mahadevan, Tamil-Brahmi Inscriptions of the Sangam Age, preprint, II International Conference-Seminar of Tamil Studies, Madras, 1968. For the discussion of the two types of Old Tamil, cf. also K. Zvelebil “The Brahmi Hybrid Inscriptions”, Archiv Orientální (1964) 545-575, and id., From Proto-South Dravidian to Old Tamil and Malayalam, preprint, II International Conference-Seminar of Tamil Studies, Madras, 1968.

In a somewhat different language, and in a very different style, the earliest bardic poetry, now developed, refined and transformed into bardic court-poetry, enjoyed and acclaimed, began to crystalize around certain nuclei which later became the core of the “Caṅkam” Anthologies (cca 100 B.C.-200 A.D.).

The problem is how to fit, chronologically, the Tolkāppiyam or its basic layer into this picture.

As far as the mutual relation of the language described in the Tolkāppiyam, and the language of the early Tamil-Brāhmī inscriptions, is concerned, one point is quite clear: the two represent two different types, two different “styles” of language. (This is indicated on the diagram by the curved line cutting across the arrow-head lines representing the evolution of the two basic styles of Tamil, Written and Spoken.) According to I. Mahadevan, “the orthography of written Tamil was experimental during the first two centuries of its existence … the inscriptions emerge in simple, intelligible Tamil, not very different in its matrix (that is, the phonological, morphological and lexical structure) from the Tamil of the Southern period”. In other words, the differences between the Tamil of the inscriptions (Prakritization of their vocabulary, some of which looks “archaic” and different from forms found in literary texts, etc.) and the Tamil of the ancient literature, almost contemporaneous with the inscriptions, may be accounted for by the fact that those inscriptions represent probably a spoken variety of Tamil used by the (most probably bilingual) Jaina and/or Buddhist monks, while the bardic corpus represents a literary language, which was at that period in the stage of “crystallization” and standardization. Basically, then, the language of these epigraphs, and the language described by Tolkāppiyam, are two styles, two varieties of one language—Old Tamil. Therefore, nothing prevents us from regarding them as contemporaneous or almost contemporaneous, just like, in our own days, the Tamil used by—let us say—an Iyengar Brahmin from Triplicane, Madras, discussing the arrangements for the day’s dinner with his wife, represents a different style from that employed by the authors of the Tamil Encyclopaedia preparing an article on the use of contraceptives.

A number of scholars (like R. Raghava Ayyangar, M. Raghava Ayyangar,27 V. Ventakarajulu Reddiar,28 S. Vaiyapuri Pillai, T. P. Meenakshisundaran29 and others) have clearly pointed out that there are differences between the rules in Tolkāppiyam, and the actual linguistic usage in the so-called Caṅkam texts. Since the type and style of the language are identical (standardized literary Tamil of bardic court-poetry), the Tolkāppiyam and the bardic poetry are, obviously, not quite of the same age. Was the grammar composed earlier than the bulk of “Caṅkam” poetry, or later? Let us point out first some of the more striking differences.

27 E.g. R. Raghava Ayyangar, Tamiḻ varalāṟu (Annamalai, 1941), 268273; M. Raghava Ayyangar, Ārāyccit tokuti, 306-9.

28 Cf. Vēṅkaṭarājulu Reṭṭiyār, Kapilar, 104-105.

29 Cf. T. P. Meenakshisundaran, A History of Tamil Language (1965), 51; C. and H. Jesudasan, A History of Tamil Literature (1961), 3-4.

Phonemic shapes, which may be considered earlier, occur in the grammar; the same words appear in what may be considered later phonemic shapes in the bardic poetry, e.g. Tolk. viyar: Porunar. 80 vēr “sweat”; Tolk. yāṭu: Puṟ. 229 āṭu “goat, sheep”; Tolk. yāru: Neṭunal. 30 āṟu “river”.

There is a restriction on the occurrence of the palatals in the Tolk.; according to sūtras 62, 64, 65, the palatal c, ñ and y cannot be followed by a; but this restriction is no more valid for the bardic poems, in which a number of words occur with the palatals followed by a (cf. Puṟ. 14.9, 56.18, 74.3 and elsewhere).30 Honorific plurals, allowed by Tolk. Col. 27 only in the spoken language, occur in the literary texts of the “Caṅkam” age (Aiṅk. 431-440). The restrictions on the use of the verb vā* “to come” and tā* “to give” (used only with the first two persons), cel “to go” and koṭu “to give” (used only with the third person, cf. Tolk. 512, 513) are no longer valid in the “Caṅkam” period. The usage of the particles of comparison, prescribed in Tolk., is relaxed in “Caṅkam” works. The restriction of the viyaṅkōl. “implied command”, to the third person, is not valid for bardic texts (Tolk. 711). There had also been some semantic shift, e.g. tuñcal in Tolk. Poruḷ. 260 means “to sleep”, while in Patiṟ. 72 it means “to die”; kavarvu “to desire” (Tolk. Col. 362) means “to eat” in Paṭṭiṉap. 22. According to Tolk. Col. 269, el means “light”, in Malaipaṭuk. 416 it means “night”.

30 Cf. items like caṭai (Puṟ. I), camam (Puṟ. 14), cakaṭam (Puṟ. 102), cavatṭi (Perumpāṇ. 217), calam (Maturaik. 112), cantu (Malaipaṭuk. 392), cavaṭṭum (Patiṟṟup. 84), camam (Tirukkuṟaḷ 99), camaṉ (ib. 112), which show that the rule of Tolk. Elutt. 62 must have preceded these forms and, hence, these texts.

These and other differences between the language, described in the Tolkāppiyam, and the language used by the bards in their heroic and erotic poems argue rather for an earlier date of the grammar, since a literature following a grammar may “add” its own “rules” (and it usually does so), while the reverse procedure is highly improbable. Since, however, the general political, social and cultural conditions as reflected by the Tolkāppiyam and the classical bardic poetry are more or less the same, and—more important—the deep structure and the stage of evolution of the language of the bardic poetry and the metalanguage of Tolkāppiyam are, too, almost identical, there could hardly have been a wide gap of time between the two.

Our first conclusion: the earliest, original version of the Tolkāppiyam belongs to the “pre-Caṅkam“ period; the oldest layer of the grammar is somewhat earlier in time than the majority of extant classical Tamil poems.

The relations between Patañjali, an early Sanskrit grammarian, and the Tolkāppiyam, seems to be well established. It looks as if Tolk. Col. 419 is indeed indebted to Patañjali’s classification of compounds into pūrvapadārtha-, uttarapadārtha-, Ianyapadārtha-* and ubhayapadārtha-. In fact, Tolk. Col. 419 seems to be almost a translation of Patañjali’s Sanskrit text.31

31 This is the Tamil version: avai tām / muṉmoḻi nilaiyalum piṉmoḻi nilaiyalum irumoḻi mēlum oruṅku taṉ nilaiyalum / ammoḻi nilaiyātu aṉmoḻi nilaiyalum annāṉku eṉpa poruḷnilai marapē (Col. 419).

Cf. this with the Sanskrit text: iha kaścit samāsāḥ / pūrvapadārtha pradhānaḥ kaścit uttarapadārtha pradhānaḥ / kaścit anyapadārtha pradhānaḥ / kaścit ubhayapadārtha pradhānaḥ. I think S. Vaiyapuri rightly stressed the fact that neither Pāṇini nor Kātyāyana divide compounds according to this fourfold scheme; it seems that this division is characteristic for Patañjali, and hence there is a special connection between Patañjali’s Mahābhāṣya and the Tamil Tolkāppiyam (Mahābhāṣya is the “great commentary” of Patañjali on the sūtras of Pāṇini and the vārttikas of Kātyāyana).

32 Cf. Tolk. Col. 27. Before Patañjali, only the term vyākaraṇa- was used to denote “grammar”. Cf. also Tolkāppiyaṉ’s use of the loan-translation kuṟi “sign” (cf. Skt. lakṣaṇa- in the same meaning) to denote “grammar” in Tolk. Poruḷ. 50. These points are discussed at length in Tamil by S. Vaiyapuri in his Tamiḻc cuṭar maṇikaḷ (ed. 1959) p. 50.

S. Vaiyapuri Pillai also points to Tolkāppiyaṉ using the term ilakkaṇam <Pkt. lakhana-, Skt. lakṣaṇa- in the sense of “grammar”; this, he says, was first introduced by Patañjali (cf. HTLL, p. 49).32

The date of Patañjali’s Mahābhāṣya is given as approximately 150 B.C.33

33 A. B. Keith, History of Sanskrit Literature, p. 5.

34 Tamiḻc cuṭar maṇikaḷ, 3rd ed., 46-48 and HTLL p. 13.

It also seems that Tolkāppiyaṉ knew Pāṇini. S. Vaiyapuri Pillai quotes a few instances of this. Thus, the “four-parts-of-speech” system of Tolkāppiyam (Col. 158, 159: noun, verb, particle, qualifier) seems to correspond to the fourfold system of Pāṇini (nāma- “noun”, ākhyāta- “finite verb”, upasarga- “dependent determinative word”, nipāta- “particle”), though Tolkāppiyaṉ’s division is first and foremost based on the actual state of affairs in Tamil and agrees admirably with modern linguistics (the Tamil system is noun, adjective, verb, particle). We may probably also connect Tolk. Elutt. 83 with Pāṇini.34

Granting the indebtedness to Pāṇini, this would give us the 4th-5th Cent. B.C. as the lower limit for Tolkāppiyam. Since, however, we consider the Tolkāppiyam, even in its original form anyhow much later than that date, this lower limit is not so very important.35

35 For the date of Pāṇini, cf. M. B. Emeneau, Collected Papers, p. 188, ftn. 3: “Probably not earlier than the sixth century B.C. nor later than the fourth (so Franklin Edgerton, Word Study, vol. xxvii / 1952 /, b. 3, p. 3), perhaps even to be pinned down to the fifth century B.C. (M. Winternitz, op. cit., p. 42), even to the middle of that century (V. S. Agravala, India as known to Panini / Univ. of Lucknow, 1953, p. 475)”.

Much more important is the fact that some of the nūṟpās of the Tamil grammar seem to have been directly influenced by much later Sanskrit texts.

The possible agreement between Mānavadharmaśāstra III.46, 47 and Tolk. Poruḷ. 185 would immediately raise our lower limit to about 200 A.D.

A very possible agreement between the enumeration of the 32 uktis in Kauṭilya’s Arthaśāstra and Tolkāppyaṉ’s 32 uttikaḷ would raise the lower limit further, to about 300 A.D.36

36 M. Winternitz, Geschichte der indischen Literatur, III, 523.

37 P. R. Bhandarkar, Indian Antiquary 41 (1912) 158. The two texts in question run as follows:

śṛngāra hāsya karuṇā raudra vīra bhayānakāḥ

bībhatsādbhuta saṃjñau cētya nāṭyerasāḥ smṛtāḥ

(Nāṭyaś. VI. 15)

nakaiyē yaḻukai yiḷivaraṉ maruṭkai

yaccam perumitam vekuḷi yuvakaiyeṉ

ṟappā leṭṭē meyppā ṭeṉpa

(Tolk. Poruḷ. Meyp. 3)

The equivalents are, obviously, Ta. nakai = Skt. hāsya “fun; laughter”; Ta. aḻukai Skt. karuṇā “compassion; weeping”; Ta. iḷivaral bībhatsa “ridicule, disgust”; Ta. maruṭkai Skt. adbhuta “wonder, confusion”; Ta. accam = Skt. bhaya “fear”; Ta. perumitam = Skt. vīra “conceit, arrogance; heroism”; Ta. vekuḷi Skt. raudra “wrath, anger”; Ta. uvakai = Skt. śṛngāra “pleasure”.

In Tolk. Poruḷ. 251, the eight feelings (moods) and/or their physical manifestations are enumerated; and these, according to S. Vaiyapuri Pillai, clearly agree with the eight rasas or “moods” of Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra VI.15. I am very much convinced that in this point, Tolk. Poruḷ. is indebted to the Sanskrit source (or sources) beyond any doubt whatsoever. Bharata’s date is usually given as 4th Cent. A.D., so that Tolk. Poruḷatikāram would be later than the 4th Cent. A.D., if the Tamil grammar indeed imitated the Sanskrit treatise.37

The ten avattai, “states”, described by Tolkāppiyaṉ in Poruḷ. 100 correspond clearly to the daśāvasthāḥ of Kāmasūtra 5.1. This would, again, give us a later date than the 4th Cent. A.D. for Tolk. Poruḷatikāram.38

38 M. Winternitz, Geschichte der indischen Literatur, III, 540.

One can of course always object that, before all these cultural matters became fixed in dateable texts, they might have been and probably were current in the cultural traditions of the “Sanskritic” people; hence, allusions to them are no real help in dating. Also, lines containing these allusions might be considered as later interpolations.

According to S. Vaiyapuri, there is yet another additional proof for a rather late date of the grammar in the use of the word ōrai,39 which seems to be most probably a Greek word (hōrā) borrowed into Sanskrit astrological texts about the 3rd-4th Cent. A.D. (A. B. Keith).40

39 maṟainta oḻukkattu ōraiyum nāḷum, Kaḷaviyal 45.

40 Tamiḻc cuṭar maṇikaḷ, p. 54.

Last but not least, Tolk. Poruḷ. 53 shows familiarity with the dramatic idiom and the common usage portrayed in the rather late, “post-Caṅkam” texts of Kalittokai and Paripāṭal.

Before reaching a conclusion—or even before expressing our agreement (or disagreement) with S. Vaiyapuri Pillai’s conclusion—we must, however, observe one fact: all the correspondences between later (post-Christian era) Sanskrit texts and the Tamil grammar occur in the Poruḷatikāram, in the third book of Tolkāppiyam. In other words, there are a few lines in the Poruḷatikāram which are almost certainly of very late origin, not earlier than the 5th Cent. A.D. Ruling out a transfer of cultural materia through channels other than direct influence of Sanskrit texts, and ruling out later interpolations and additions of precisely these lines, this fact would give us approximately the 5th Cent. A.D. as the earliest possible date of Poruḷatikāram, and as the date of the final redaction of the Tolkāppiyam. This is our second, but not our final conclusion.

The question is now: Should we accept S. Vaiyapuri Pillai’s conclusion that Tolkāppiyar “must have lived in the 5th Cent. A.D.”? Or, in other words, that the whole of Tolkāppiyam was written as late as the 5th Cent. A.D.?

There is a certain amount of inconsistency between some of the sūtras of the grammar. It also seems that some of the sūtras have been “tampered with” and rearranged. This would suggest that certain sūtras are later interpolations. On the other hand, there are some gaps in the treatment of a few topics, which would suggest that the grammar has not reached us in absolute integrity.41

41 Cf. T. P. Meenakshisundaran, A History of Tamil Language (1965), pp. 51-52. E.g. in Tolk. 1503, 1510, 1573, the word piḷḷai “young one” is said never to occur with reference to “human child”; but in Tolk. 1106 the same word means “human child”. Or: the last few sūtras in the last chapter of the 3rd book seem to be unnecessary repetitions of statements about nūl “book” made already in the previous chapters on prosody. Such sūtras may be considered later additions.

42 In the prefatory stanza, Paṇampāraṇār qualifies Tolkāppiyaṉ as aintiram niṟainta, i.e. “full of”, “well-versed in” aintiram.

43 Cf. Belvalkar, Systems of Sanskrit Grammar, p. 11. “As for the diversity and extent of Indian grammatical work: about twelve different schools of grammatical theory have been recognized in the Indian tradition (most, if not all, to some degree dependent on Pāṇini), and there are about a thousand separate grammatical works preserved” (J. Lyons, Introduction to Theoretical Linguistics, 1968, p. 19).

It is suggested here, therefore, that the present text of the Tolkāppiyam, which underwent final editing and redaction sometime in the 5th Cent. A.D. or later, is rather the work of a grammatical school than of an individual author. The school in question was probably called aintiram, a pre-Pāṇinian grammatical system ascribed to Indra.42 The term aintiram (<aindra-) itself is post-Pāṇinīan, and Pāṇini does not mention it. This aindra system of grammar continued to exist, however, long after Pāṇini and was followed mainly by Jains (its representant being, e.g., Kātantra of the 3rd-4th Cent. A.D.).43 It is probable that the author(s) of the bulk of the grammatical sūtras which became known as Tolkāppiyam belonged to the group of Jaina scholars, following this aindra grammatical tradition. However, the organization of the grammar, and some other features of the text indicate that, apart from a possible number of authors involved there probably was a single master-mind who grasped with exceptional insight and intuition the deep grammatical structure of Tamil; who observed the emergence of Tamil as a full-fledged literary language, distinct from other closely related speeches like Kannada; who helped to institutionalize and standardize this vehicle of literature, and made explicit, in a highly formalized way, the rules of that language and its particular style. Thus, the nuclear portions of Tolkāppiyam were probably born sometime in the 2nd or 1st Cent. B.C., but hardly before 150 B.C.

Later generations of grammarians and prosodists added to this core and developed its ideas from time to time, and it is not ruled out that the third part of the grammar, the one which deals with the subject-matter of poetry, is in toto (or in greater part) later than the first two parts. The final redaction of the Tolkāppiyam as we know it today did not very probably take place before the 5th Cent. A.D., so that the ultimate shape of the sūtras as we have them before us is probably not earlier than the middle of the first millennium of our era.

The intellectual achievement of the author(s) of Tolkāppiyam—in spite of the lack of utmost brevity and economy—is indeed enormous. As already said, it is a vision of an entire civilization, highly formalized and made very explicit. All the three books show a mind of extraordinary depth, a rare inwardness, a brilliant expository power, and an ability of crystal-clear formulation.44

44 S. Vaiyapuri Pillai, HTLL, p. 71.

In general approach, Tolkāppiyam, like the work of Pāṇini, is a descriptive, strictly synchronic grammar, dealing with one style of the language, the Early Old Literary Tamil. Like Pāṇini, Tolkāppiyaṉ gives much attention to phonetics, and to the internal structure of words. His statements seem to be based on observation and experiment. Though well organised, very consistent, and very exhaustive, the Tolkāppiyam has not surpassed or even reached the level of Pāṇini in economy, expliciteness, consistency and terseness. On the other hand, the field of experience the Tolkāppiyam—as a total text in its final shape—describes, is much wider and even deeper than that of Pāṇini. To illustrate this point, let us analyse a few of the nūṟpās occurring at the beginning of Akattiṇaiyiyal (the first chapter of the 3rd book of the grammar), since the reader is already familiar with the basic concepts occurring in this text from Chapter 6 (The Theory of “Interior Landscape”). However, while in the previous chapter the literary implications were considered, here we shall deal with the basic conceptual framework of Tolkāppiyam, with the gnoseological attitude of the first and most ancient of great Tamil intellects.

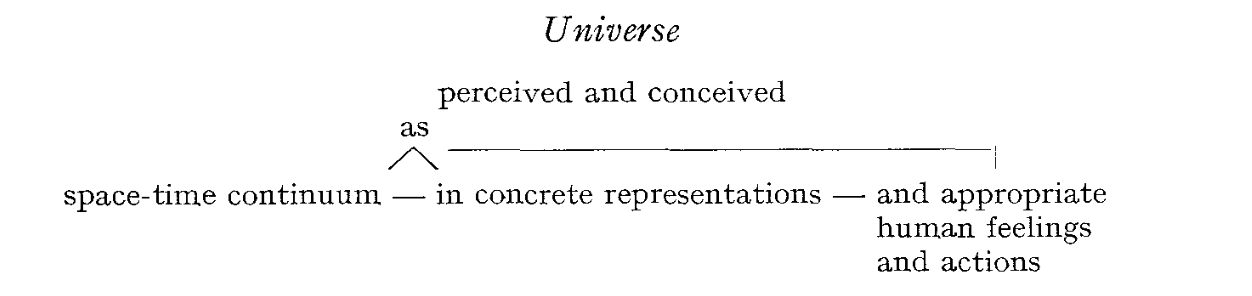

True to the characteristic intellectual thoroughness, and obeying a basic urge toward learned classification, the author of these lines observes the entire universe, all objects in the world which appears to him as perceived―kāṭci45—and conceived—karuttu46—in terms of three categories of entities (poruḷ): mutal, karu and uri.47 Mutal, 48 or Mutaṟporuḷ, or the basic, first entities, in terms of which the phenomenal world may be described, are TIME (poḻutu) and SPACE (nilam). That is, the time-space continuum, the dimensions of space and time; space and time are indispensable; everything must be perceived and conceived within its time-space coordinates. Karu49 (lit. “foetus, embryo, egg, germ”, cf. DED 1074) are things (poruḷ) “born, native”, i.e. entities which appear as concrete, natural, “inborn”, “native” representations of the time-space coordinates. Uri (lit. “own, related, suitable, proper; essential”, DED 563) are “essential, appropriate” entities, i.e. human feelings and situations “proper, appropriate” to the various time-space divisions. Schematically:

45 kāṭci, DED 1209 “sight, vision of a deity, view, appearance”; in this connection, “perception, vision”.

46 karuttu, DED 1078 “design, purpose, opinion, attention, desire, judgement, mind, will”; in this connection, “conception”.

47 Tolk. Poruḷ. Akat. 3: mutalkaru vuripporu ḷeṉṟa mūnrē etc. “the three (types of) entities: the basic (or first), the germinal (or womb-like) [and] the proper (or own)”.

48 ib. 2: mutaleṉa paṭuvatu nilampoḻu tiraṇṭiṉ / iyalp(u) …

49 Accord. to Poruḷ. Akat. 18, “gods, food, beasts, trees, birds, drums, occupations, melody-types etc.” and the commentator adds, under the “etc.”, (tribal or generic) name of the hero and the heroine, the waters, the habitat, the flowers, and the (tribal) designation of the people.

For the subdivision of time (polutu, kālam), the reader may consult chapter 6. The space, the stage set for humans to “fight and mate”, was “perceived and conceived” by Tolkāppiyaṉ in terms of the cultural regions, of the landscapes, of the physiographic divisions. These regions had their concrete manifestations in the karu paradigm, and, under the uri or “appropriate entities”, each of the landscapes had a corresponding human physical and psychological situation.50 Nature and man were conceived as different (nature under mutal-nilam, and man typically under uri), but, at the same time, as being in one-to-one correspondence, in striking parallelism, and, above all, in “harmony” and unity. Natural phenomena, behaviour of beasts and birds, and descriptions of natural scenery, were frequently used as symbolic, indicative and inferential for human feelings and actions. There was no strict division between “nature” and “art”, between “natural” as nonhuman, and “art-ificial”, “civilized”, “cultural” as human.51

50 This being what A. K. Ramanujan so happily termed “interior landscape”.

51 Which does not mean that there was no distinction between “beast” and “man”. On the contrary; the language, and its grammatical description, make a sharp distinction between rational ( human and divine, uyartiṇai), and the ir-rational (= animal, vegetative and inanimate, aẖṟiṇai).

The very first nūṟpā of Tolk. Poruḷ. Akatt. speaks about seven behaviour-patterns or tiṇai; it says that, beginning with “one-sided love” and ending with “excessive love”, there are seven tiṇais. The details have been discussed in Chapter 6. Here we would like to add one point: in TP Akatt. 5, Tolkāppiyaṉ calls these regions ulakam (< Skt. loka- “world”), i.e. “worlds”, since, indeed, these regions constituted miniature worlds with their own characteristic cultures. It is also significant that the same nūrpā enumerates only the four regions (pasture lands, mountains, agricultural tracts, littoral regions) which are constantly inhabited and “cultivated”, i.e. cultured, leaving pālai “wasteland, desert” unmentioned. The world is called characteristically nāṉilam in classical Tamil, i.e. “four-fold region”. Nūrpā 14 of TP Akatt. gives the five behaviour-patterns, the five psychosomatic situations: puṇartal “sexual union”, pirital “separation”, iruttal “patient waiting”, iraṅkal “pining” and ūṭal “sulking”.

It can hardly be claimed that this “intellection” and classification of the world and of human beings was the “invention” of Tolkāppiyaṉ. However, since Tolkāppiyam has given it its final shape, this categorization and these conventions went under its author’s name and, as pointed out above, exerted a lasting influence upon the Tamil mind.

9.1 Appendix

The translation of the beginning of the Tolkāppiyam (Eluttatikāram) is given here so that the reader may have an idea of the highly technical nature of the work.

The eḻuttu are said to be

thirty in number

beginning with a

[and] ending with ṉ

except the three the occurrence of which

depends upon others.They [the three] are

the over-short i, the over-short u,

and the three dots

called āytam, similar to a eḻuttu.

Among them,

the five sounds

a, i, u, e, o

have each one measure

[and] are called short sounds.The seven sounds

ā, ī, ū, ē, ai, ō, au

have two measures each

[and] are called long sounds.One [single] sound has never three measures.

Learned men say that if lengthening is needed, the [sound]

of that measure should be produced and added.According to the view of those who have

understood accurately,

one māttirai is the time taken by a wink of the eyes

[or] a snap of the fingers.The twelve phonemes ending with au

are called vowels.The eighteen phonemes ending with ṉ

are called consonants.The nature of vowels is not altered

even when pronounced with consonants.The measure of a consonant is said

to be half [of a māttirai].The other three also remain of that nature.

The sound m has [its] half measure shortened when pronounced with [another consonant].

Considered carefully, this is rare.[Its] shape will be a dot obtained within.

The nature of the consonant

is to be provided with a dot.