10 The Book Of Lofty Wisdom

“there hardly exists in the literature of the world a collection of maxims in which we find so much lofty wisdom” (A. Schweitzer, Indian Thought and Its Development, 1960, p. 199).

The facts about the Tirukkuṟaḷ, formulated as briefly as possible, are as follows: It is a comprehensive manual on ethics, polity and love, consisting of 1330 distichs divided into 133 sections of 10 distichs each; the first 38 on ethics (aṟam), the next 70 on political and economic matters (poruḷ), and the rest on love (kāmam). The author was probably a learned Jain with eclectic leanings and intimate acquaintance with the early works of Tamil classical period, as well as with some knowledge of the Sanskrit legal and didactic texts. We have almost no authentic information on his life. As the best date of the Kuṟaḷ one may suggest 450-550 A.D.

This chapter will deal with the Tirukkuṟaḷ exclusively from the point of view of its structure: structure of content, structure of metre, structure of language. By structure we understand a set of interrelated items which have no validity independently of the relations which hold among them.

Thus, this chapter will not entirely ignore, but deal only with utmost brevity, with such problems as the author’s person, the date of the work, and its “ideology”.

The Tirukkuṟaḷ has always been in the highest esteem among the Tamil people. This great reverence for the author and his work is reflected by the nine different names under which the book goes:1 1. Tirukkuṟaḷ, lit. “The sacred kuṟaḷ”, 2. Uttaravētam “The ultimate Veda”, 3. Tiruvaḷḷuvar (= the author’s name, “Saint Vaḷḷuvar”), 4. Poyyāmoḻi “The falseless word”, 5. Vāyuṟai vāḻttu “Truthful praise”, 6. Teyvanūl “The divine book”, 7. Potumaṟai “The common Veda”, 8. Muppāl “The three-fold path”, 9. Tamiḻmaṟai “The Tamil Veda”.

1 In addition to these traditional names, three more titles occur (Tiruvaḷḷuvappayaṉ in Yāpparuṅkalakāvikai 40 urai, Tamiḻmuṉunūl in Parimēlaḻakar’s Commentary, and Tiruvaḷḷuvamālai, cf. S. Vaiyapuri Pillai, Tamiḻc cuṭar maṇikaḷ 101). According to S. Vaiyapuri, Nos 1, 4, 5 and 8 are taken from Tiruvaḷḷuvamālai, a later eulogy, a collection of stanzas in praise of the poet and his work, ascribed to gods and poets of the Maturai academy. The name Tamiḻmaṟai is also based on ideas occurring in the eulogy, stanzas 24, 28, 37, 42. No. 7 occurs in Kallāṭar’s and Veḷḷivītiyar’s stanzas. According to the same scholar (Tamiḻc cuṭar maṇikaḷ 101-102), the original name of the book, given by the author himself, had most probably been Muppāl, or (in analogy with Nālaṭiyār) simply Kuṟaḷ. Though purely a speculative conclusion, it is not improbable.

2 Cf. Es. Vaiyāpurip Pillai, Tamiḻc cuṭar maṇikaḷ, 3rd ed., 1959, Pāri Nilaiyam, Madras, pp. 77-96.; S. Vaiyapuri Pillai, History of Tamil Language and Literature, 1st ed., 1956, Madras, pp. 79 ff.; C. and H. Jesudasan, op. cit., pp. 41 ff.

The historical problem of the date of the Tirukkuṟaḷ is rather complicated, and it has been thrashed out in a number of papers and books, published in Tamil as well as in Western languages. The internal evidence (the language of the work, allusions to earlier works, indebtedness of the Kuṟaḷ to some Sanskrit treatises, etc.) all points to a date which is considerably later than the early classical poetry (and in this respect the Kuṟaḷ does certainly not belong to the “Caṅkam” age), but earlier than the beginnings of bhakti in Tamilnad. The 5th Cent. A.D., probably sometime between 450-550 A.D., is the best date that can be suggested.2

There are, as usual, a number of conflicting traditions about the author. One tradition says that he was an outcaste by birth, the issue of an union between a Brahmin and a Pariah woman. Some think that he was a weaver by caste,3 others say that he “must have been” a vēḷāḷa since he praised agriculture, the traditional occupation of the caste, so highly. A scholar equates vaḷḷuva with vallabha and takes the term to mean a superintendent, an officer of the king.4 Another, and a more probable opinion was expressed by S. Vaiyapuri Pillai (HTLL, p. 80) that Vaḷḷuvar was “the chief of the proclaiming boys analogous to a trumpet-major of an army”.5

3 Cf. Pope’s translation, 1886, i: “The weaver of Mayilâpûr”.

4 M. Raghava Iyengar, Ārāyccittokuti, 1964, 206-209.

5 cf. DED 4353 Ta. vaḷḷuvaṉ a Pariah caste, the members of which are royal drummers, and priests for Paraiyas. Ma. vaḷḷuvaṉ a priest of the Parayas, a low-caste sage, a caste of slaves.

6 Pope began his missionary life in 1840 in Mayilāpur. The 19th Century Christian-oriented morality was responsible for the standpoint of early translators of the Kuṟaḷ towards its third book on kāmam “pleasure”. Of this book Drew said that “it could not be translated into any European language without exposing the translator to infamy”. And Pope adds: “But this is only true in regard to certain of the commentaries upon it, which are simply detestable … Kâman is the Hindû Cupid … This prejudice kept me from reading the third part of the Kurraḷ for some years” (Introd. xii-xiii).

Almost every religious group in India has claimed the Tirukkuṟaļ for itself, including the Christians. G. U. Pope sees the poet as an eclectic, who came, in Mayilāpur, into contact with Christian teachers (like Pantaenus of Alexandria), “imbibing Christian ideas, tinged with the peculiarities of the Alexandrian school, and day by day working them into his own wonderful Kurraḷ”. It is Pope who speaks of the book as an”echo of the ‘Sermon on the Mount’ “. Pope, himself a Christian missionary,6 was rather overenthusiastic in discovering strong traces of Christianity in Tiruvaḷḷuvar’s work.”I cannot feel any hesitation in saying that the Christian Scriptures were among the sources from which the poet derived his inspiration” (Introduction, iv). However, whatever may remind us of the Sermon on the Mount belongs rather to the sphere of “natural law”; and the ethics of the Kuṟaḷ rather a reflection of the Jaina moral code than of Christian ethics (cf. e.g. Tiruk. 251-260 on vegetarianism, Tiruk. 321-333 on “not killing”, kollāmai).

While the hypothesis of Christian influence is based on vague impressions, it is a fact that we find in the text several purely Jaina technical terms; and it seems that Tiruvaḷḷuvar had been “cognizant of the latest developments” of the Jaina system.

The Kuṟaḷ’s epithets for God are very much Jaina-like: cf. malarmicaiyēkiṉāṉ (Tiruk. 3) “he who walked upon the (lotus) flower”; aṟavāḻiyantaṇaṉ (ib. 8) “the Brahmin (who had) the wheel of dharma”; eṇkuṇattāṉ (ib. 9) “the one of eight-fold qualities” (kuṇam < Skt. guṇa-). These epithets of God (besides ātipakavaṉ “the Primeval Lord”, cf. Manu 1.6, and iṟaivaṉ “the King, the Monarch”) are very well applicable to the Jaina Arhat (e.g. “standing on a lotus flower”) and to none else; this even the orthodox Hindu commentator Parimēlaḻakar had to admit. Two of the other attributes, given by Vaḷḷuvar to his God, have a strong ascetic flavour, and suggest, too, Jaina atmosphere. In Tiruk. 4 we find vēṇṭutal vēṇṭāmai ilāṉ “he who has neiter desire nor aversion”, in 6 poṟivāyil aintavittāṉ “he who has destroyed the gates of the five senses”. So, if there is at all any reflection of a particular doctrine in the work, it is rather the Jaina terminology and the Jaina atmosphere (cf. Tiruk. 251-260, 321-330) which we find in the text.

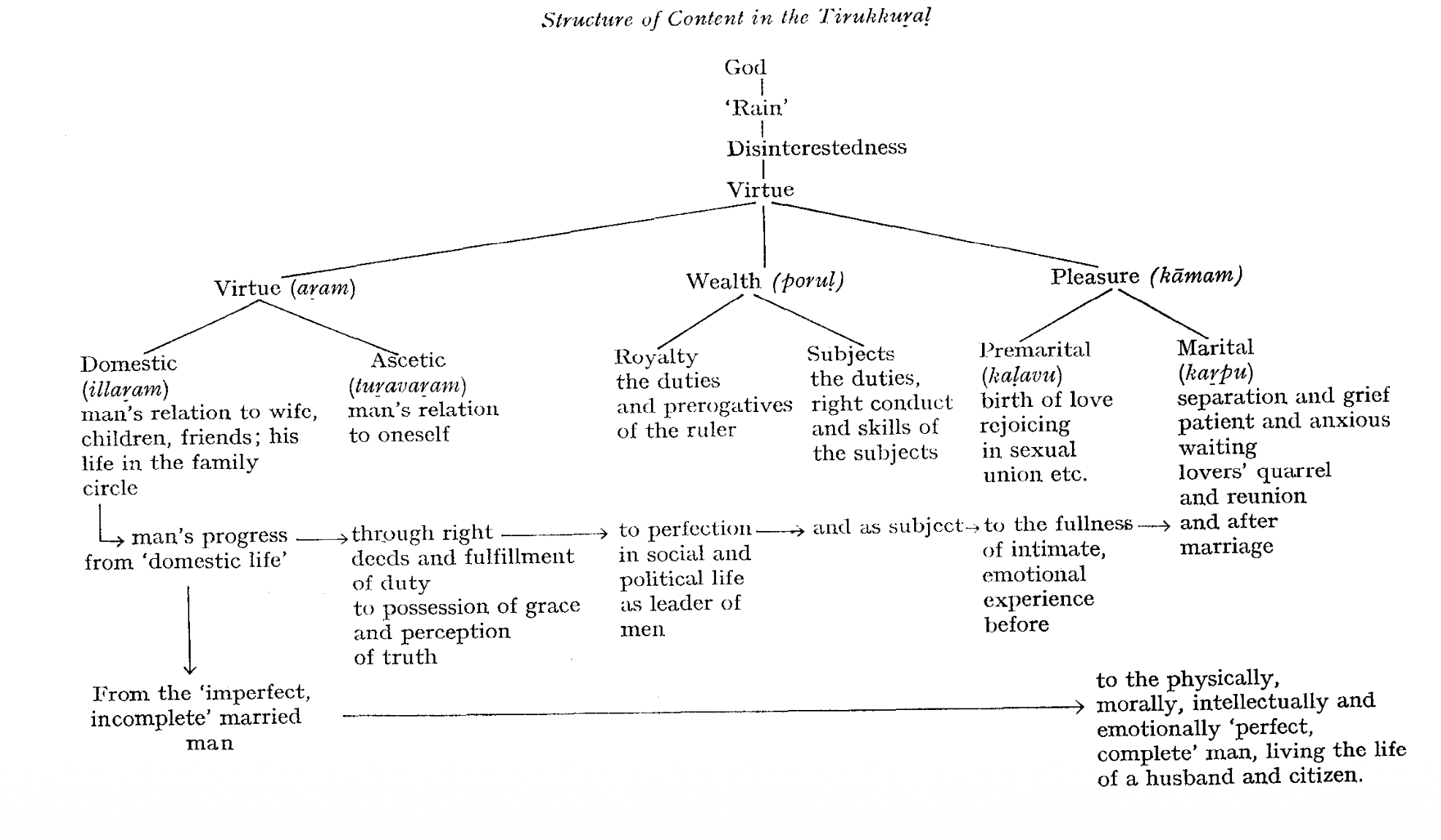

Aram (dharma “virtue”), poruḷ (artha “wealth”) and kāmam (kāma “pleasure”) are dealt with in the work. There is no specific portion allotted to the fourth and “highest” objective of life, to vīṭu (mokṣa “deliverance”). It is not because Vaḷḷuvar had left his work incomplete. Not because “he thought his people were not prepared for the higher teaching”.7 But simply because Vaḷḷuvar’s moral code was eminently empirical, practical, pragmatic: this life, this world, man in his relation to this material world, to society and state, to his beloved, his children and family, and to his own inner life—that was what thrilled Vaḷḷuvar; not “heaven” (vīṭu). That this interpretation is valid may also be seen from the schematic representation of the content-structure which shows that the progression, the movement is from the “imperfect”, “incomplete” married man, husband and lover, through subsequent steps of perfection, to the “perfect”, “complete” family-man, husband and lover, and not towards an ascetic, a recluse. God and virtue as such, and “disinterestedness” of those “who, way of both worlds weighed / In this world take their stand, in virtue’s robe arrayed” (23), is common to all spheres and stages of life, just like rain (vāṉ, maḻai) falls upon all.

7 That a wise and knowledgeable man like Pope could make such a judgement is hardly credible.

It seems that, as far as its language, formal structure and content-structure is concerned, the Kuṟaḷ is the work of a single author.

The very division into the three major parts—the aṟattuppāl (the part on virtue), poruṭpāl (the part on wealth) and kāmattuppāl (the part on pleasure)—may be and probably is the author’s. The name Muppāl, “(A work) of three parts”, and the fact that all commentators agree with this basic three-fold division, support this conclusion. However, any further division of the text beyond that seems to be later, since the commentators and scholiasts differ: thus, the first book is divided, by Parimēlaḻakar, into two parts, illaṟam (“domestic virtue”) and tuṟavaṟam (“ascetic virtue”) plus four chapters as payiram or “introduction”. But there are others who divide the first book into four portions. As far as the second book is concerned, there is even more variation. Parimēlaḻakar divides it into three portions, other scholiasts into five or even six parts. It seems, though, that the poet himself was responsible for the basic structure of the book and for the sequence of individual couplets; the content seems to be organized dichotomously. Also, there do not seem to be any later additions to the text.8 The Tirukkuṟaḷ is certainly not an anthology. It is the work of one poet, revealing a single structural plan. 9 The structure of the content is given schematically on the pertinent Chart (Figure 10.1). The contents of the work in detail is as follows:

8 Mrs. S. Kokilam makes me aware of the interesting fact that the number seven played obviously some role in the structural build-up of the book. Every veṇpā (couplet) has seven feet (4 + 3); the total number of couplets in the book is 1330, which, as 1 + 3 + 3 + 0, equals 7. The number of graphemic units in the author’s name is also seven: ti-ru-va-ḷ-ḷu-va-r.

9 “… the perfect and most elaborate work of one master” (Pope, Preface, iv).

Book I. Virtue (aṟam). Aṟattuppāl.

- In praise of God (pakavaṉ, iraivaṉ).

- The excellence of rain (vāṉ, maḻai).

- The greatness of those who have renounced.

- Assertion of the strength of virtue.

- Domestic life (ilvāḻkkai).

- The goodness of wife (= vāḻkkaittuņai ‘the life’s help’).

- The obtaining of sons (putalvar).

- The possession of affection (aṉpu).

- Hospitality.

- Kindly speech.

- Gratitude.

- Impartiality.

- Self-control.

- Decorous conduct.

- Not coveting another’s wife.

- Forbearance.

- Absence of envy.

- Absence of covetousness.

- Not speaking evil of the absent.

- Not speaking senseless words.

- Dread of evil deeds.

- Recognition of duty.

- Giving.

- Fame (pukaḻ).

- Possession of grace (aruḷ).

- Abstinence from flesh (vegetarianism).

- Penance (tavam).

- Inconsistent conduct.

- Absence of fraud.

- Truthfulness.

- Absence of anger.

- Inflicting no pain.

- Not killing (kollāmai).

- Instability of earthly things.

- Renunciation (tuṟavu).

- Perception of truth (mey).

- Extirpation of desire (avā).

- Past deeds (ūḻ = karma).

Book II. Wealth (poruḷ). Poruṭpāl.

- The greatness of a king.

- Learning.

- Ignorance.

- Learning through hearing.

- Possession of knowledge.

- Correction of faults.

- Seeking the help of the great.

- Avoiding mean association.

- Acting after right consideration.

- Recognition of power.

- Recognition of opportunity.

- Recognition of place.

- Selection and confidence.

- Selection and employment.

- Cherishing one’s kin.

- Unforgetfulness.

- The right sceptre.

- The cruel sceptre (tyranny).

- Absence of tyranny.

- Benignity.

- Spies.

- Energy.

- Unsluggishness.

- Manly effort.

- Not despairing in trouble.

- Ministry.

- Power in speech.

- Firmness in deeds.

- Method of action.

- The envoy.

- Conduct in the presence of king.

- Knowledge of signs.

- Knowledge in the council chamber.

- Not to fear the council.

- The land.

- The fort.

- Way of accumulating wealth.

- Greatness of the army.

- Military spirit.

- Friendship.

- Scrutiny of friendship.

- Familiarity.

- Evil friendship.

- Faithless friendship.

- Folly.

- Ignorance.

- Hostility.

- The excellence of hate.

- Skill in the conduct of quarrels.

- Secret enmity.

- Not offending the great.

- Being led by women.

- Wanton women.

- Abstinence from liquor.

- Gaming.

- Medicine.

- Nobility.

- Honour.

- Greatness.

- Perfect excellence.

- Courtesy.

- Useless wealth.

- Shame.

- How to sustain the family.

- Agriculture.

- Poverty.

- Mendicancy.

- The dread of mendicancy.

- Vileness.

Book III. Pleasure (kāmam). Kāmattuppāl.

- Mental disturbance caused by the lady’s beauty.

- Recognition of the signs.

- Rejoicing in the sexual union.

- In praise of her beauty.

- Declaration of love’s excellence.

- Abandonment of reserve.

- Rumour.

- Separation is unendurable.

- Complaining of absence.

- Eyes concerned with grief.

- Grief’s pallor.

- Solitary anguish.

- Sad memories.

- Visions of night.

- Laments at evening.

- Wasting away.

- Soliloquies.

- Reserve destroyed.

- Longing for return.

- Reading of the signs.

- Desire for reunion.

- Arguing with one’s heart.

- Lovers’ quarrel.

- Petty jealousies.

- Pleasures of temporary variance.

The content of the Tirukkuṟaḷ is undoubtedly patterned. In fact, it is structured very carefully, so that no “structural gaps” occur in the text. Every single couplet is indispensable for the structured whole. Every distich has, so to say, two kinds of meaning: if isolated and thus removed from the content-structure, the couplets lose a very important meaning—component—their “structural meaning”. An isolated couplet may be charming and interesting in itself, but it is just a “wise saying”, a moral maxim, a “literary proverb” in perfect form, possessing, in varying degree, the prosodic and rhetoric qualities of gnomic poetry. It acquires a “structural meaning” only in relation to other couplets, forming higher patterns, and, finally, in relation to the entire text, which forms a perfect total structure. This fact is in sharp contrast with the early classical poetry, where each stanza was a perfectly self-contained unit; various stanzas were gathered in anthologies; while, as already stressed, the Tirukkuṟaḷ is not an anthology.

Man in the totality of his relationships is the sujet of the Kuṟaḷ. After a “cosmic” introduction, which praises God, rain, supermen and virtue, the author of the book turns towards man, whose personality is gradually unfolded in “ever expanding concentric cycles” within the family with his wife and children, within the community with his friends, and within his country, in his relationship towards the ruler and the state. Man is shown not in a static state but in development, and the force that is behind this dynamism is sympathy, even love, manifesting itself through kind thought, sweet words, and right actions. At the end of the first part, in Chapter 24, this stage of one’s development ends by attaining true fame (pukaḻ). However, the gradual unfolding of man’s personality goes on on a higher level: through benevolence, through the grace of universal love (aruḷ, Chapter 25). Abstaining from all injury, fraud, anger, falsehood and, above all, from killing,10 the mind becomes pure, and the man becomes wise. He attains real knowledge11 and universal love; there is, for him, no distinction between “you” and “I”12; he is free.13

10 E.g. 322: “Let those that need partake your meal; guard everything that lives: this is the chief and sum of lore that hoarded wisdom gives”.

323: “Alone, first of good things, is”not to slay”; / The second is, “no untrue word to say”.

11 E.g. 352: “Darkness departs, and rapture springs to men who see / The mystic vision pure, from all delusion free”.

12 E.g. 346: “Who kills conceit that utters”I” and “mine”, / Shall enter realms above the powers divine”.

13 E.g. 365: “Men freed from bonds of strong desire are free; / None other share such perfect liberty”.

But man’s relationship to himself, to his own soul, and his private, intimate life, is only one aspect of human life on this earth. There is also man’s relationship towards society, towards the state, his place in the hierarchies and orders, his relationship towards the king; the material and social basis of his existence; his public life; in short—man, the zoon politikon.

It is in this second book on “Wealth” (poruḷ) that the Tirukkuṟaḷ is not only a book of noble, “lofty” wisdom, but also a book of shrewd cunning. Here, the moral is very empirical, very pragmatic. It is true that Tiruvaḷḷuvar approaches even these worldly matters from the aspects of friendship, kindness, justice:

“Search out, to no one favour show, with heart that justice loves.

Consult, then act, this is the rule that right approves”

—

(Pope, 541).

It is true that the Tirukkuṟaḷ despises tyranny and that his monarchy has many features of “modern democracy”14 (if that is to be considered a compliment). But we also read such couplets as e.g.

14 Cf. T. P. Meenakshisundaran, HTL, p. 58. Cf. e.g. 566: “The tyrant, harsh in speech and hard of eye, / His ample joy, swift fading, soon shall die”.

“Make money! Foeman’s insolence o’ergrown

To lop away no keener steel is known”

—

(Pope, 759).

Or,

“Destroy the thorn, while tender point can work thee no offence.

Matured by time, ’twill pierce the hand that plucks it thence”

—

(Pope, 879).

However, one should never contemplate the couplets in isolation. We must again and again stress that they have true validity and meaning only in their patterned relations to other couplets, and to the whole. And when read and contemplated in this way, Tiruvaḷḷuvar’s ethics is never that of a Cāṇakya or a Macchiavelli. Even in single couplets, kindness and friendship will show as an unavoidable accompaniment of other qualities:

“Fierceness in hour of strife heroic greatness shows:

Its edge is kindness to our suffering foes”

—

(Pope, 773).

What is, however, even more important is the fact that the public life of man, man as a political being, is discussed only after his inner, moral growth had been described; only a cultured, a civilized man, a man who is morally and spiritually ripe, is ready to enter public, political life. This is the basic “structural” meaning of the whole second part of the book.

It is the third part of the work, the Kāmattuppāl, which contains some of the most “poetic” couplets. The reason is clear; it is in this part dealing with “pleasure” that the traditions of early classical literature, of the “Caṅkam” poetry, are still strong. Every couplet in the third part may be considered a”dramatic monologue of the akam variety”15. The man who has unfolded his personality in the moral and spiritual order and who is taking part in the social and political life, is also entitled to pleasure, and to strictly private life. In fact, only a meaningful relationship with woman, physical and emotional, makes him “whole”. After spiritual treasures and moral wealth, there is emotional richesse; after exercising his intelligence and knowledge, there is the heart which must not be neglected. The hypertrophy of virtue, as well as the hypertrophy of skills and prowess, would be catastrophic; beauty, leisure, feelings and emotions are indispensable parts of human life. And in the Kāmattuppāl, we have the lover and his sweetheart in physical and emotional rapture, described in about 250 charming couplets:

15 Cf. T. P. Meenakshisundaran, HTL, p. 53.

“Shall I draw back, or yield myself, or shall both mingled be,

When he returns, my spouse, dear as these eyes to me”

—

(Pope, 1267).

“Withdraw, it burns; approach, it soothes the pain;

Whence did the maid this wondrous fire obtain ?”

—

(Pope, 1104).

“A double witchery have glances of her liquid eyes;

One glance is glance that brings me pain; the other heals again”

—

(Pope, 1091).

If there is true poetry anywhere in the Tirukkuṟaḷ, it is here, in the erotic couplets of the third book. Because here, the teacher, the preacher in Vaḷḷuvar has stepped aside, and Vaḷḷuvar speaks here almost the language of the superb love-poetry of the classical age.16

16 Tiruvaḷḷuvar’s Kāmattuppāl is utterly different from any of the Sanskrit Kāmaśāstras. While Vātsyāyana’s work (and all later Sanskrit erotology) is śāstra, that is, objective and scientific analysis of sex, the third part of the Kuṟaḷ is a poetic picture of eros, of ideal love, of its dramatic situations.

As far as the prosodic form of the work is concerned, a perfect unity prevails throughout the entire text in that it employs one kind of metre which is eminently suitable to gnomic poetry. The veṇpā is the most difficult, and the most highly esteemed of stanzaic structures of classical Tamil literature. There are five different kinds of this stanza. The Tirukkuṟaļ uses just one of them, the kuraļveṇpā. Here are its structural properties:

- Only feet of three or two metrical units may be employed.

- The stanza must always end in a foot of the following type: —, =, — ◡, = ◡ .

- Strict rules of consonance of lines must be observed (so-called veṇṭoṭai).

- The number of feet is seven, the number of lines two: the first line contains four feet, the second three feet.

As an instance, a typical kuraḷveṇpā (393) is quoted here:

kaṇṇutaiya reṉpavar kaṟṟōr mukattiraṇṭu

puṇṇuṭaiyar kallā tavar

“The learned men alone are said to have eyes:

the unlearned have but a pair of sores in their face”.

Its metric structure is:

Observe, how the above-said rules are strictly adhered to: the couplet has four feet in the first, three feet in the second line. The feet are of two (— =, — —) or three (— = —, = = —) metric units only. The couplet ends with a foot of the so-called malar (=) shape. The “rhyme” occurs in the coda of the first syllable: kaṇṇ- / puṇṇ-. Observe, too, how closely and intimately the formal properties and the content are connected: kaṇ “eye(s)” and puṇ “sore(s)” are placed in the most prominent, most “functional” slots in the lines; they bear the “rhyme” (etukai); because, semantically, these two words express the contrast between learning (“having eyes”) and ignorance (“having sores instead of eyes”).

No wonder that this perfect form which is so closely connected with the structural properties of the Tamil language, and which is a marvel of brevity and condensation, has proved an insurmountable obstacle for all translators of the work. What H. A. Popley said about this problem is unfortunately very true: “It is impossible in any translation to do justice to the beauty and force of the original”.17

17 H. A. Popley, The Sacred Kuṟaḷ. Calcutta and London, 1931, p. x.

It is precisely this perfect form which—apart from the structural properties and the “structural” meaning discussed above—adds to the sometime rather banal sounding “sayings” the “beauty and force” these couplets undoubtedly possess in the original. This brings us to the discussion of another, rather delicate, matter.

The question posited by some (notably the old iconoclast K. N. Subrahmanyam) whether the Tirukkuṟaḷ is at all poetry, is not so senseless and unwise as some scholars have indicated.18 I would not at all hesitate to raise the question, but I would certainly hesitate to answer it positively without much thought. Is Tiruvaḷḷuvar to be regarded as a (great) poet or not?

18 Cf. T. P. Meenakshisundaran, HTL, p. 59: “… his work cannot be denied the title of poetry”.

Tirukkuṟaḷ is a great work; and its author must have been a great man, and a great genius; “the venerated sage and lawgiver of the Tamil people”, as Pope says. But only occasionally, only rarely is he a great poet. True and great poetry appears in brief flashes here and there in the text (notably in the third book) in a few forceful metaphors and happy similes. The author’s supreme skill in handling the metre is of course undeniable.

However, quite obviously, the aestetic function, the evoking of rasa, i.e. poetry, art as such and in itself, had not been the main aim of Tiruvaḷḷuvar.

He was not a poet but a teacher; not art, but wisdom, justice, ethics is the basis of his work; his aims are gnomic, didactic, instructive. And he is great precisely because in spite of these basic goals, he also attains perfection of form and he, too, occasionally appears as a great poet.19 “That which above all is wonderful in the Kuṟaḷ is the fact that its author addresses himself, without regard to castes, peoples or beliefs, to the whole community of mankind; the fact that he formulates sovereign morality and absolute reason; that he proclaims in their very essence, in their eternal abstractedness, virtue and truth; that he presents, as it were, in one group the highest laws of domestic and social life”.20 Tiruvaḷḷuvar is “the great ‘Master of the Sentences’” (Pope). But this “bard of universal man” is emphatically not “the greatest poet of South India” as Pope calls him.21 It is also not true that “Tiruvaḷḷuvar has made every maxim a beautiful verse of wonderful poetry”.22 There are couplets in the text which are just skillful veṇpās containing some platitude or even banality, and not the slightest attempt has been made by their author to even strife after poetic greatness.23

19 Cf. such sweet and charming similes as in 1121 “The dew on her white teeth, whose voice is soft and low, / Is as when milk and honey mingled flow”. Or 1289: “Love is more tender than an opening flower”. Or such striking comparisons as in 552: “As ‘Give’ the robber cries with lance uplift, / So kings with sceptred hand implore a gift”. Or 1078: “The base, like sugarcane, will profit those who bruise”, or 80: “Bodies of loveless men are bony framework clad with skin”. Cf. metaphors like in 853 “the grievous plague of enmity”, 1221 “thou art not evening, but a spear that does devour the soul of brides”, 1166 “a happy love is a sea of joy”, 1227 “This grief is a bud in the morning, all day an opening flower, a full-blown blossom in the evening”, 1232 “eye wet with dew of tears”. Or such pregnant and forceful lines as 1075 accamē kīḻkaḷa tācāram “Fear is the base man’s virtue”.

20 M. Ariel, in a letter to E. Burnouf, published in Journal Asiatique (Nov.-Dec. 1848), quoted by Pope (Introd. i).

21 What of Kampaṉ, and Iḷaṅkōvaṭikaḷ, and the early classical poets like Kapilar and Paraṇar, and the great epic poets in Telugu and Kannaḍa? According to Pope, “in value it (= the Kuṟaḷ) far outweighs the whole of the remaining Tamil literature” (Introd. iii)! We can naturally never agree with Pope on this point.

22 T. P. Meenakshisundaran, The Pageant of Tamil Literature (1966) 19.

23 E.g. 582: “Each day, of every subject every deed, / ’Tis duty of the king to learn with speed”. Or 584: “His officers, his friends, his enemies, / All these who watch are trusty spies”. Or 616: “Effort brings fortune’s sure increase, Its absence brings to nothingness”. (The original is equally banal and poor as the translation, but for a pun upon the word inmai: muyarci tiruvinai yākku / muyarcinmai yinmai pukutti viṭum).

But, on the whole, taken as an integrated vision of man and his development, one can understand why such reader of the Kuṟaḷ as G. U. Pope composed a sonnet on the poet; and, cum grano salis, one may agree with Pope when he says that Tiruvaḷḷuvar touched “all things with poetic grace”.

Let it be said in conclusion that it is almost impossible to truly appreciate the maxims of the Kuṟaḷ through a translation. Tirukkuṟaḷ must be read and re-read in Tamil. This fact, too, reveals something about the nature and degree of its “poetic excellence”.

10.1 Appendix: The language of Tirukkuṟaḷ

A number of important grammatical innovations occur in the language of this text when compared with the early old Tamil of the classical period: the plural suffix -kaḷ is used with both nouns of the “higher” and “lower” class (cf. 263 maṟṟaiyavarkaḷ, 919 pūriyarkaḷ); the conditional suffix -ēl occurs frequently (368 uṇṭēl, 655 ceyvāṉēl, 556 iṉṟēl etc.); negative forms in -āmal belong to the innovations, too (101, 103 ceyyāmal, 1024 cūḻāmal); there are more of such features which show that, linguistically, the Tirukkuṟaḷ cannot be contemporaneous with (or older than) the “Caṅkam” poems, but later.24

24 For a complete linguistic analysis of the text, cf. J. J. Glazov, Morphemic Analysis of the Language of Tirukkuṟaḷ, in Introduction to the Historical Grammar of the Tamil Language, Moscow, 1967, 113-176.

There is definitely a higher percentage of Sanskrit loanwords in the Tirukkuṟaḷ than in the Tolkāppiyam and in the “Caṅkam” works. A complete list is given in S. Vaiyapuri Pillai’s Tamilccuṭarmaṇikaḷ, pp. 72-3. Since I have a comment to offer on these loans, the list is reproduced here in toto.

- akaram (1)

- aṅkaṇam (720)

- accu (475)

- aṭi (636)

- antam (563)

- amar (814)

- amarar (121)

- amiḻtam (11)

- amaiccu (387)

- araṅku (401)

- aracar (381)

- araṇ (381)

- avam (266)

- avalam (1072)

- avi (259)

- avai (323)

- ākulam (34)

- ācāram (1075)

- ācai (266)

- āṇi (667)

- āti (1)

- āyiram (259)

- icai (231)

- intiraṉ (25)

- imai (775)

- irā (1168)

- ilakkam (627)

- uru (261)

- uruvu (667)

- ulku (756)

- ulakam (11)

- ulaku (1)

- uvamai (7)

- uru (498)

- ēmam (306)

- ēr (14)

- kaẖcu (1037)

- kaṇam (29)

- kaṇicci (1259)

- katam (130)

- kantu (507)

- kaluḻum (1173)

- kavari (969)

- kavuḷ (678)

- kaḻakam (935)

- kaḷam (1224)

- kaḷaṉ (730)

- kaṉam (1081)

- kāmam (360)

- kāmaṉ (1197)

- kāraṇam (270)

- kārikai (571)

- kālam (102)

- kāṉam (772)

- kuṭaṅkar (890)

- kuṭi (171)

- kuṭampam (1029)

- kuṇam (29)

- kulam (956)

- kuvaḷai (1114)

- kūr (599)

- kokku (490)

- koṭi (337)

- kōṭṭam (119)

- kōṭṭi (401)

- camaṉ (118)

- calam (660)

- civikai (37)

- cutai (114)

- cūtar (932)

- cūtu (931)

- takar (486)

- tavam (19)

- tāmarai (1103)

- tiṇmai (54)

- tiru (168)

- tukil (1087)

- tulai (986)

- tūtu (681)

- teyvam (43)

- tēyam (753)

- tēvar (1073)

- toṭi (911)

- tōṭṭi (24)

- tōṇi (1068)

- tōḷ (149)

- nattam (235)

- nayam (860)

- nākam (763)

- nākarikam (580)

- nāmam (360)

- nāvāy (496)

- niccam (532)

- nīr (13)

- nutuppēm (1148)

- pakkam (620)

- pakuti (111)

- paṭam (1087)

- paṭivattar (586)

- paṇṭam (475)

- pakavaṉ (1)

- patam (548)

- payaṉ (2)

- parattaṉ (1311)

- paḷiṅku (706)

- paḷḷi (840)

- pākam

- pākkiyam (1142)

- pāvam (146)

- pīḻikkum (843)

- pīḻai (658)

- puruvam (1086)

- pūcaṉai (18)

- pūtaṅkaḷ (271)

- pēṭi (614)

- pēy (565)

- maṅkalam (60)

- maṭamai (89)

- matalai (449)

- mati (636)

- mantiri (639)

- mayir (964)

- mayil (1081)

- maṉam (7)

- maṇi (1273)

- mā (68)

- māṭu (400)

- māṉam (384)

- mīṉ (931)

- mukam (90)

- yāmam (1136)

- vañcam (271)

- vaṇṇam (561)

- vaḷai (1157)

- vaḷḷi (1304)

- vittakar (235)

- vēlai (1221).

Now from this list we have to exclude a number of items which were considered to be Aryan loanwords by S. Vaiyapuri Pillai, but which have since been proved, mainly by the labours of Burrow and Emeneau, to be of Dravidian origin. The lexis of Tirukkuṟaḷ is thus not so heavily Sanskritized after all. The following items have to be regarded as Dravidian in origin:

- amar (DED 137)

- uru (DED 608)

- ēmam (DED 760)

- ēr (DED 2313)

- kavari (DED 1115)

- kavuḷ (DED 1124)

- kaḻakam (DED 1132)

- kaḷam, kaḷan (DED 116)

- kuṭi (DED 171)

- kūr (1578)

- kōṭṭam (1709)

- takar (2430)

- tiṇmai (2634)

- tukil (2687)

- tōṭṭi (2925)

- tōḷ (2940)

- nayam (2977)

- nir (3057)

- pakuti (3154)

- paṇṭam (3220)

- paḷḷi (3309)

- pēṭi (3631)

- pēy (3635)

- maṭamai (3798)

- mayir (3854)

- mayil (3793)

- mā (3923)

- miṉ (3999)

- mukam (4003)

- vaḷai (4348)

- vaḷḷi (4351)

- vēlai (4555)

Some items are of uncertain etymology; thus e.g. uru, uruvu (DED 566) may or may not be a lw. < Skt. rūpa-.

The Sanskritic vocabulary of Tirukkuṟaḷ shrinks considerably; from 137 items to about 102 items. And if a more intensive etymological work were done, it may still shrink (cf. the uncertain etymology of such items as kuṭaṅkar, kaluḻ, etc., which may ultimately prove to be Dravidian).

A few of the metaphors in the text seem to be loan-translations from Sanskrit, e.g. piṟavip peruṅ kaṭal “the ocean of rebirths”: Sanskrit saṃsārasāgara-. Just as there is a not negligible influence of Sanskrit vocabulary on Tiruvaḷḷuvar’s lexis, the author of the Kuṟaḷ is undoubtedly to some extent indebted to Sanskritic sources like Mānavadharmaśāstra, Kauṭilya’s work etc. Thus Tirukkuṟaḷ 43 is almost a translation of Mānav. III.72, Tirukkuṟaḷ 54 is a vague echo of Manav. IX.12, Tiruk. 58 of Mānav. v. 155, Tiruk. 396 about learning has a parallel in Mānav. II.212, Tiruk. 501 (the method of testing candidates for ministerial office) is based undoubtedly on Kauṭilya I.10 (upadhā- “the moral test”), Tiruk. 385 mentions the same four kinds of acts of a kind as those stated in Mānav. VII.99, 100 and Kāmāndaka I.20., etc. However, this is, in itself, of no great importance; it would be foolish to deny that Tiruvaḷḷuvar, a mind so universal, cultured, learned and eclectic, knew these basic Sanskrit sources on dharma and niti. He was without doubt a part of one great Indian ethical, didactic tradition. It is more important that he was also a very integral part of the non-Sanskritic and pre-Sanskritic Tamil tradition; this fact is seen not only from his conception of “pleasure” which is so typically a reflexion of the akam genre, but also from the all-pervading pragmatic, this-wordly, empirical and, to a great extent, humanistic and universalistic character of his particular conception of dharma and nīti.