6 The Theory Of “Interior Landscape”

In this chapter I shall deal in detail and in a more formalized manner with the remarkable and to a very great extent independent and original theory of literature, worked out some time at the beginning of our era and systematized and codified some time in the early half of the first millennium A.D. The pertinent material to be discussed is presented in form of charts and diagrams, and the text is a kind of commentary on these.

First, however, it is necessary to say a few words about the sources of this theory.

There are three basic theoretical works in classical Tamil which deal with the earliest conventions of Tamil literature: Iṟaiyaṉār’s Akapporuḷ (IA) or Kaḷaviyaḷ, the third part of Tolkāppiyam called Poruḷatikāram (TP), and Aiyaṉār Itaṉār’s Puṟapporuḷ veṇpā mālai (PVM). These texts will be now discussed one by one, in their probable chronological order.

Today, Iṟaiyaṉār Akapporuḷ and its commentary by Nakkīrar form an integral text, and for most Tamil scholiasts, the commentary is more important than the underlying book. However, there is probably a wide gap of time between the two. It seems that Iṟaiyaṉār’s Akapporuḷ is the first “grammar of love” in Tamil culture, older than TP, that it is the earliest attempt to systematize, classify and explain the bardic poetry and its conventions, themes and subject-matter as a “classical”, that is a “closed”, “frozen”, “traditional” body of texts which ceased to be alive.1 Reasons:

1 Some authors maintained that the rigid adherence to the conventions “crushed poetic freedom and originality” (M. S. Purnalingam Pillai, op. cit. p. 18). Some other authors would see in the classification, codification and explanation of the traditional conventions, given in the grammars, notably in TP, almost a whim of the grammarians and scholiasts, and they took a very negative stand towards such procedures (S. Vaiyapuri Pillai, HTLL: he speaks about “the utterly artificial, or at best conventional character of the treatment”, of “artificialities” which “had never any influence on the development of Tamil literature”, which “today have no meaning except for the antiquarian”, op. cit. pp. 69-70). For some critics, applying neo-romantic literary criteria to ancient oral and post-oral literature of the classical age, imitation is unbecoming of poets; imitative verses are necessarily of inferior quality (M. Varadarajan, The Treatment of Nature …, pp. 412 and elsewhere, Raja Manickam, op. cit. 204 ff.). These critics are indeed very incorrect in their conclusions. First of all, no so-called creative act is entirely free (even a titanic artist like Michelangelo was necessarily limited, e.g. by the demands of Pope Julius and the extent of the space in the Sistine Chapel). Old Tamil poets did emphatically not sing “like birds” (as e.g. P. T. S. Iyengar says). On the contrary, the classical Tamil poet is, first of all, par excellence an “objective” type (in R. Wellek’s sense of the term), open to the world, obliterating his concrete personality, with a very weak or almost nonexistent element of personal expression, like the poet of the Renaissance age, like the bard of chivalric romances. The poetry of the classical Tamil age is a sophisticated poetry, full of conventional formulae, based on traditional subject-matter, fed on traditional similes, metaphors, allusions and suggestions. The material which was codified, classified and interpreted in the grammars was not a late ex-post ratiocination, or an anthology of the grammarian’s whims, but, originally, while the bardic tradition was still alive, these were the useful guidelines for instruction and aid how to compose poetry; later, after the live bardic tradition died and became part of a classical past, these sūtras came to be regarded as useful guidelines for the reader. They were based on actual usage of the poet for whom they had once formed a framework of references and limitations within which he was “free to sing”, or rather free to prove how good his power of improvisation was. The original framework, the ancient prototypes of the formulae and themata, the basic original conventions must have been based ultimately upon reality. This was true of both genres: the conventions built up around love-poetry were ultimately based on real life, on erotic experience of the people living in the hills and forests, in the fields and on the seashore; allusions to heroic deeds which later became symbolic, allegoric, and part of the technique of suggestion, were based on actual historical events preserved in the memory of generations. That and only that had been the period when the first poets (not yet bards or minstrels of any status, but a kind of folksingers) sang “like birds”. But of this period we have absolutely no direct testimony. Of this “primeval”, simple, “folk” poetry of the ancient Tamils nothing whatsoever has survived. What has survived, is a highly developed bardic poetry, composed in accordance with the rules and limitations imposed by tradition and formalized by the first theoreticians.

2 The episode is blended with myth and fiction, but may contain a grain of truth: Once upon a time a severe famine occurred in the Pandya land. Many people had to leave, and among them were bards and scholars patronized by the king. Many years later they returned, the king convened the bards and discovered that there was no book on poetics and rhetoric (poruḷatikāram), but only the two books on “letters” (eḻuttatikāram) and “words” (collatikāram). Since the king and the members of the “Academy” had no “grammar of the Matter” (poruḷilakkaṇam peṟātu, ed. 1939, p. 14), god Śiva (= Iṟaiyaṉār) himself intervened and composed the Akapporuḷ. Hence, Iṟaiyaṉār Akapporuḷ is sometimes translated as “The Lord’s Grammar of Love”.

3 The age was now very different from the “bardic” age—Tamilnad went through a strong impact of Jaina and Buddhist moralizing, pessimistic trends, reflected in the didactic literature, and subsequently through the first impact of neo-Brahmanism reflected in early bhakti texts like the Tirumurukāṟṟuppaṭai and Kāraikkāl Ammaiyār’s poems.

4 Cf. such passages as e.g. on s. 2: ivaḷum uṭan piṟantu uṭaṉ vaḷarntu nīr uṭaṉ āṭi cīr uṭaṉ peruki ōl uṭaṉāṭṭup pāl uṭaṉuṇṭu pal uṭaṉeḻuntu col uṭaṉ kaṟṟu paḻamaiyum payiṟciym paṇpum naṇpum … etc. This is very much the style of a late Tamil poet rather than of a medieval scholiast who tended to be more simple and less verbose (cf. Iḷampūraṇar’s style, who was, in “time-depth”, the very next commentator). The number of similes is staggering.

First, the fact that, in IA, the literary theory, the poetics and rhetoric is much less elaborate and much more roughly and less delicately presented than in Tolk. Poruḷ. Second, the commentary says explicitly, that IA is the first book (mutanúl) on akam.2 The name of the author is Iṟaiyaṉār, and this has been explained by the commentary and by the tradition as “God”, i.e. Siva himself. There is a poem in Kur. (No. 2) ascribed to one Iṟaiyaṉār. There is nothing to refute the hypothesis that the author of the late bardic poem and the author of the theoretical work were one and the same man. The commentary also says that the book was composed at the time of the third Caṅkam, during the reign of Ukkirap Peruvaḻuti. The legend referred to in ftn. 1, p. 86 may indicate (although it is rather vague speculation) that at the time when IA was composed, the TP was not yet in existence. On the other hand, there is much in the body of the aphorisms (sūtras) that shows a relatively late origin of the book. The very first sūtra which gives the definition of kaḷavu or premarital love shows that the Brahminic influence (which has by that time surpassed the Jaina and Buddhist impact) was fully established: it says that kaḷavu is called that type of marriage among the eight (described by) the Vedic tradition of the Brahmins (antaṇar arumaṟai) which has been called the gandharva type (kantaruva) by the wise. Or, cf. s. 36, where it is maintained that for the “high-class people (uyarntōrkku)” two kinds of occupation are suitable: ōtal (“reciting of the Vedas”) and kāval (“protection”). The commentary quite rightly explains uyarntōr as Brahmins and kings or kṣatriyas. This again shows a firmly established Sanskritization and Brahminization of Tamilnad. However, quite naturally, the text contains much very ancient material, classified and described in the sūtras which are based, after all, on the early classical poetic texts, and on the tradition of bardic “handbooks”. It seems therefore that IA is the first treatise on the conventions of the earliest bardic poetry of the akam genre written down at a time when the live bardic oral tradition of that poetry was already moribund: approximately between the 4th-6th Century A.D.3 The text of the sūtras is lucid, continuous and brief. There are two parts in the grammar, one on kaḷavu (premarital or clandestine love), the other on kaṟpu (conjugal love). There are 33 sūtras in the first portion and 27 in the second. More prominence is given to kaḷavu, and hence the work has also been called Kaḷaviyal. The entire text has thus 60 sūtras. The commentary is ascribed to Nakkīrar, the son of the accountant of Maturai (Maturai kaṇakkāyaṉār makaṉār Nakkīrar). It is the first and earliest of the great prose commentaries which occupy so prominent a place in the development of Tamil scholarship and prose. It begins with a lengthy and detailed account of the legend of the three Caṅkams, the story about Uruttira Caṉmaṉ, and how the only true commentary to Iṟaiyaṉār’s book was that of Nakkīrar. It then relates how this urai was transmitted from Nakkīraṉār to his son Kiraṅkoṟṟaṉār etc. etc., until the ninth recipient of this oral transmission, a certain Muciṟi Āciriyar Nīlakaṇṭaṉār, put it into writing (iṅṅaṉam varukiṉṟatu urai). It would be very difficult, but probably possible to prove, that this Nakkīrar and the Nakkīrar who composed the very late lay “Guide to Lord Muruku”, were one and the same person. This hypothesis is supported by the analysis of the diction and style of this commentary; the prose is highly ornate and poetic, full of alliterations, similes and metaphors.4 The commentary contains many love poems (e.g. urai to ss. 7, 9, 12) which it quotes as specimen, which have not survived in the anthologies. Both the text and the commentary contain an abundance of interesting sociological, psychological and physiological data (e.g. s. 43, where the menstruation-pūppu-practices are discussed).

There are a number of Skt. loans in the commentary (e.g. vārttai, pirāmaṇaṉ, cuvarkkam, caṉam, kumāracuvāmi, vācakam, kāraṇikaṉ etc.). Important is that the commentary quotes extensively (325 out of 350 stanzas) from a Pāṇṭikkōvai (author unknown), whose hero is Pāṇṭiyan Māṟaṉ (640-670 A.D.). These stanzas belong to the 7th-8th Cent., which shows that the lower limit for Nakkīrar’s commentary is roughly 700 A.D. The upper limit would be perhaps 750-800. This does not refute the speculation that Nakkīrar of TMK and Nakkīrar the author of the commentary are identical.

Probably only slightly later than Iṟaiyaṉār, the author of Kaḷaviyal, was the man responsible for the final version and redaction of the Tolkāppiyam (we very much doubt that it was “Tolkāppiyaṉār” himself). It seems that the final and definitive version of the Tolkāppiyam Poruḷatikāram occurred sometime during the second half of the 5th—first half of the 6th Century A.D.

The Poruḷatikāram deals with different literary compositions, their subject-matter and the conventions to be observed. The sūtras which form the basis of our present definitive text of the TP may have had once the function of a bardic grammar, “an aid to the instruction of young bards” (Kailasapathy), when bardic art was still alive. Later, when the bardic art was dead and became part of the classical heritage, Tolkāppiyam became the ultimate and essential authority since it “drew freely upon many predecessors whose works were probably widely in currency, and appears as a fully developed and definitive treatise” (Kailasapathy 49), different, in this respect, from the probably slightly earlier IA.

There are indications that the core-sutras of the grammar were indeed intended for bardic instruction. So, e.g., the author refers to ten kinds of forbidden faults in literary compositions (TP 653 ff.). The very fact that TP contains material which at first sight might seem irrelevant to poetry (data on cosmology, nature, flora, fauna etc., cf. with data on physiology, hygiene etc. in Iṟaiyaṉār’s text), seems again to prove that the tradition contained in these sūtras was a teaching tradition: bardic training stresses general knowledge, and has encyclopaedic character (Kailasapathy 51, Chadwick, Poetry and Prophecy, 31-48). The classification and arrangement of the many poetic themes of love and heroism manifest unity and harmony, and in spite of some schematism, the author does not lose sight of the realities outside literature. This holds good even more of the Akapporuḷ ascribed to Iṟaiyaṉār.

Puṟapporuḷ veņpā mālai, “The garland of veṇpā (stanzas) on the subject-matter of heroism”, is a grammatical treatise of uncertain date but obviously later than TP. It seems to be a derived work, probably an abridgement of the lost grammar called Paṉṉirupaṭalam “The Book of Twelve Chapters”. It is of utmost importance for the study of heroic poetry. It also seems to have preserved a tradition to some extant different from Tolkāppiyam. According to Kailasapathy (op. cit. p. 53) it may reflect older traditions, going back to the time of the TP itself. It provides poems illustrating each theme, composed probably ad hoc for the treatise, but embodying early material. From this point of view, PVM is in some respects a literary work. Kailasapathy (op. cit. 53) quotes a few parallelisms between the illustrative stanzas in PVM and Puṟanāṉūṟu (Pur. 290 = PVM v. 19, Puṟ. 292 PVM v. 32). The authorship is ascribed to Aiyaṉār Itaṉār of the royal Cēral family.

In conclusion it may be said that all the three works discussed are later than the erotic and heroic poems themselves, and evidently contain interpolations and later additions. However, “because they were committed to writing at relatively early date, and were perpetuated by a line of scholiasts who were also in possession of oral traditional material, they more often than not provide invaluable elucidations on the bardic poems, and have become in the course of time, part and parcel of the corpus itself” (Kailasapathy, op. cit. 54). It is especially the Tolkāppiyam which has become a kind of “universal grammar” for Tamil literature of all ages. The whole problem of Tolkāppiyam, its date, its structure etc. will be discussed in detail later (cf. Chapter 9).

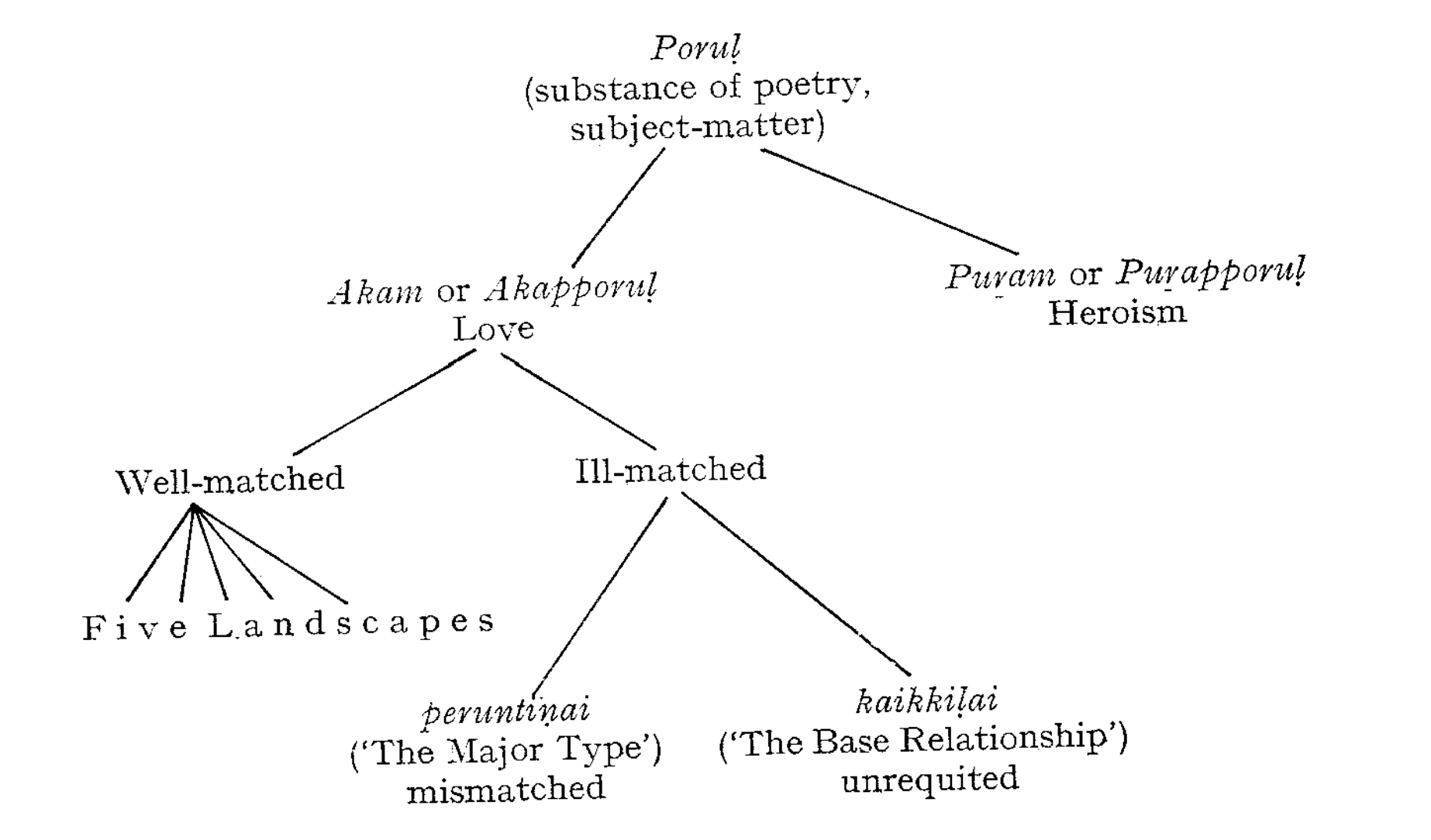

Now to the theory of literature as such. Figure 6.1 shows the basic division of the substance (poruḷ) or subject-matter, of the content of poetry.

The entire subject-matter of poetry may be divided into two main genres: akam or akapporuḷ, and puṟam or puṟapporuḷ.

- akam

- the meanings given in DED 8 are “inside, house, place, agricultural tract, breast, mind”; it occurs in all SDr languages + Tuļu and Telugu. This in itself should be rather relevant. In the cultural and literary spheres, it also means “inner life”, “private life” and, more specifically, “all aspects of love”, i.e. premarital, marital and extramarital love.

- puṟam

- in DED 3554 we read “outside, exterior, that, which is foreign”; again, the conceit occurs in all SDr languages + Tulu and Telugu. In reference to literature it means “outward life, public life, political life” and more specifically “heroism, war”.

The fundamental features of the akam genre: highly conventional poetry; the heroes should be and are fully anonymous5 and typified; their number is limited to the hero, the heroine, the hero’s friend, usually his charioteer, the heroine’s friend, usually her foster-sister and/or maid, the heroine’s mother. Under akam in its two basic divisions of kaḷavu (pre-marital love) and kaṟpu (wedded and extramarital love), the classical Tamil poet succeeded to describe the total erotic experience and the total story of love of man as such.

5 According to TP, ss. 54-5, in the five phases of akam, “no names of persons should be mentioned. Particular names are appropriate only in puṟam poetry”. In this connection, cf. W. H. Hudson, An Introduction to the Study of Literature, 2nd ed., London, 1946, p. 97: “The majority of world’s great lyrics owe their place in literature very largely to the fact that they embody what is typically human rather than what is merely individual and particular”. In this sense (and in a number of other features, e.g. the strict adherence to form, the elaborate system of conventions, the respect paid to the authority of literary precedent, etc.), “Caṅkam” poetry is directly opposed to Western romanticism, and should be rather judged and compared with the European Renaissance and the neo-classic (classicist) ages. Cf. M. Manuel, “The Use of Literary Conventions in Tamil Classical Poetry”, Proc. of the I International Conference Seminar of Tamil Studies, Vol. II, 1969, 63-69.

In contrast, the heroes of the puṟam genre are frequently individualized as concrete, historical persons (kings, chieftains, the poet himself); the drama described is based often on a single, historical event. However, there is strict conventional framework for the heroic poems, too.

From the total corpus of classical Tamil poetry, about a quarter may be ascribed to puṟam, and about three quarters to the akam genre.

Love may be well-matched or ill-matched. Well-matched love is treated in poems describing a man’s and woman’s love-experience against the background of the five basic physiographic regions; the story of human love takes part in one of the five landscapes, known technically as aim “five” + tiṇai “landscape” or aintiṇai. To each of these landscapes corresponds a particular phase of love.

Ill-matched love is again of two basic kinds: unequal, inappropriate or mismatched love or passion, technically known as peruntiṇai or “The Major Type” (is it irony?). E.g. the poems under this head deal with a man’s passion which has grown out of proportion; or with a young man’s passion for a woman much older; or with forced union due to unrestricted passion. It is the forced, loveless relationship; partners come together for duty, convenience or lust.

The other major type of ill-matched love is one-sided, unreciprocated passion, known as kaikkiḷai, i.e. “The Base Relationship”. E.g. love between a man and a maid who, being too young and unripe, does not know how to react to his feelings; his love becomes unrequited.

These two types are common, vulgar, undignified or perverted (though J. R. Marr thinks that these two aspects of love are put on one side by the theorists “cavalierly”; op. cit. 1969); they are fit only for servants. According to TP 25-26, and Ilampūraṇar’s commentary, only free men can lead a happy life. Servants and workmen are outside the five akam-types, for they cannot attain wealth, virtue and happiness; they do not have the necessary strength of character; they are moved only by passion and impulses. Only the cultured and well-matched pair is capable of the full range of love: union before and after marriage, separation, anxiety and patience, betrayal and forgiveness. The lovers should be well-matched in lineage, conduct, will, age, beauty (or figure), passion, humility, benevolence, intelligence, and wealth (TP 273).

The attitude of the theoreticians towards different types and phases of love is neither purely descriptive nor fully normative (prescriptive). It may be perhaps called “evaluative”.

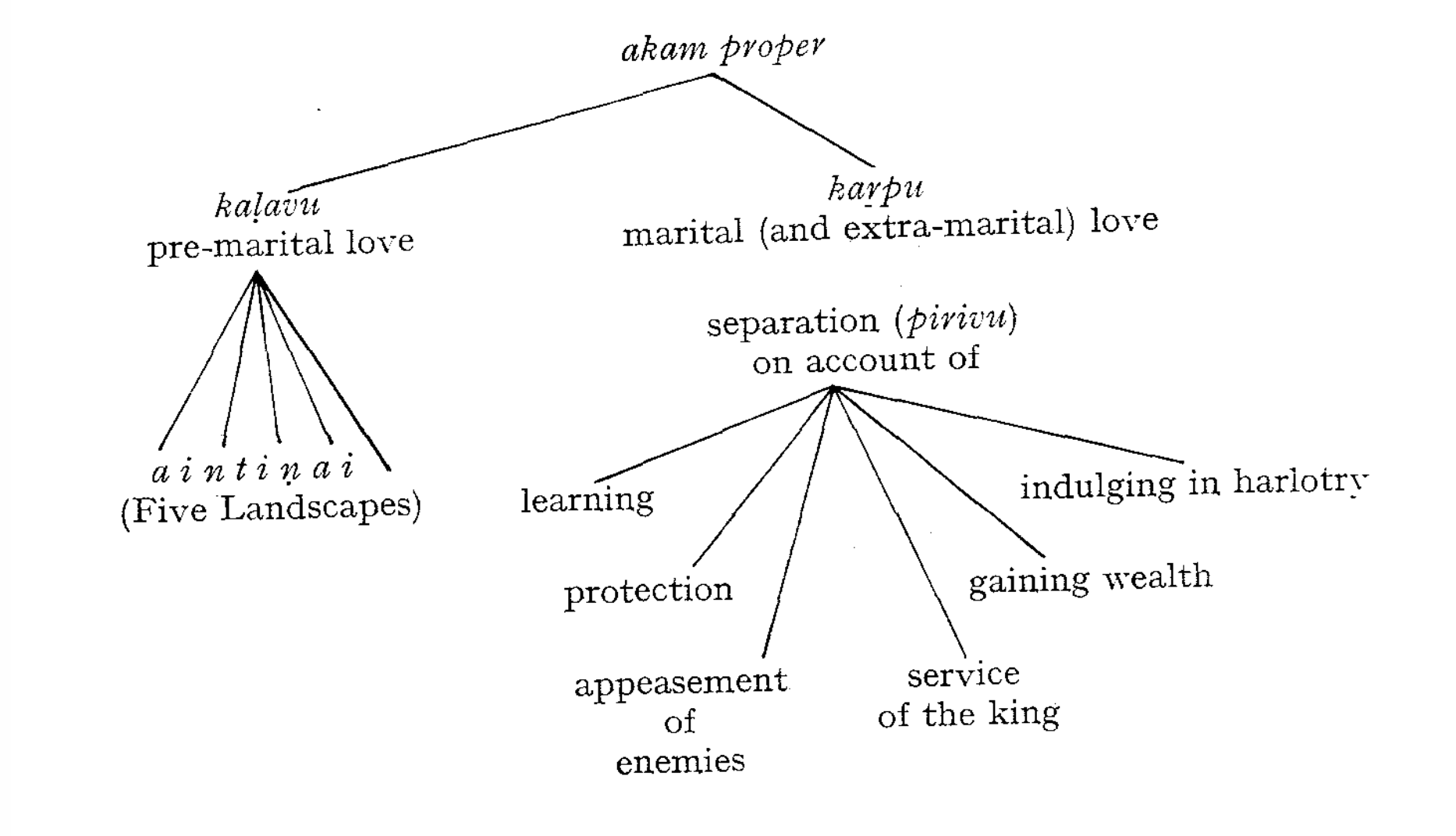

According to some theoreticians, akam proper is divided along a basic dichotomy between pre-marital union of lovers, termed kaḷavu, lit. “stealing, deceit”, and wedded, marital love, called kaṟpu, lit. “chastity” (Figure 6.2). This binary division has been elaborated especially in Iṟaiyaṉār’s Akapporuḷ. Kaḷavu, pre-wedded love, is treated in terms of the five landscapes; while the poems coming under kaṟpu describe marital and extramarital love, including the separation (pirivu) of the husband and wife on account of six different reasons: pursuit of learning, pursuit of wealth, service of the king, being engaged in the protection of the country, being engaged in the diplomatic mission, especially in the appeasement of two inimical kings, and, finally, on account of indulging in harlotry. The author of Akapporuḷ shows keen observation of human behaviour when describing what sort of men do leave their wedded wives: thus e.g. it is proper for the high-class men (according to the commentator, for the Brahmins and kṣatriyas) to leave their wives because of the pursuit of learning (ōtal, learning and reciting the Vedas) and protecting the land (kāval); to serve the king and to gain wealth is proper for the merchants and peasants (vēḷāḷar); but to leave (temporarily of course) one’s wife in order to indulge in harlotry is appropirate to all classes of men (IA s. 40). Observe the fact that visiting harlots (parattai) comes only under the edivision of kaṟpu or wedded love.

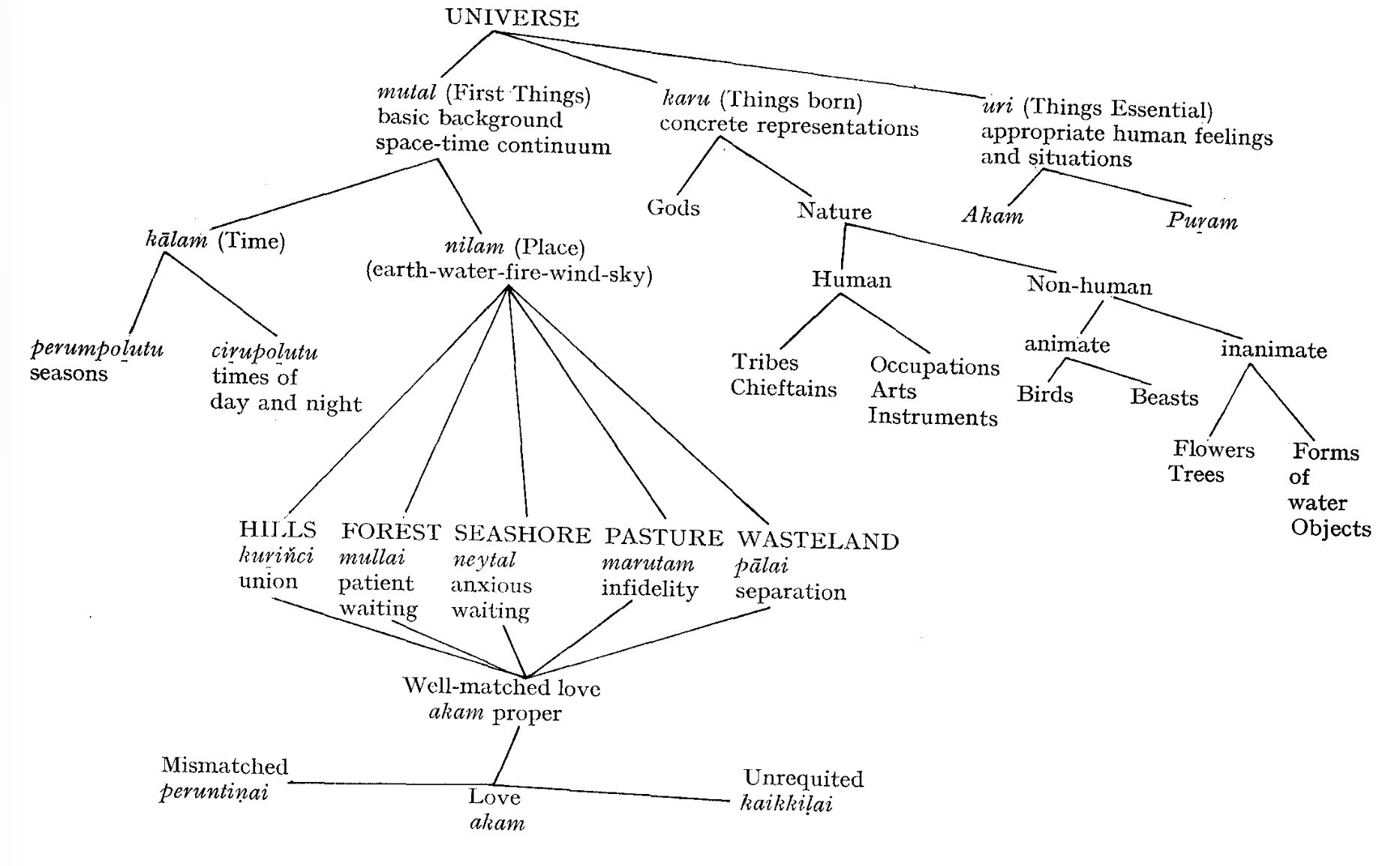

As Figure 6.3 shows, the universe is perceived (kāṭci) and conceived (karuttu) in terms of three basic categories: a space-time continuum which provides the basic background, the space and time coordinates of an event; this is termed mutal, lit. “first, basic things”, fundamental aspect, the basic stratum. The time continuum is divided into perumpoḻutu or the major seasons of the year, and ciṟupoḻutu, lit. “small time” i.e. the minor times of day and night. The space continuum, comprising the “five elements” of Indian philosophy (earth, water, fire, wind and sky), is divided into the five physiographic regions, the five major landscapes in which the drama of love takes place. Each one of these landscapes corresponds to a phase of love: the hills are a proper setting for the union of lovers; the forest corresponds to patient waiting; the seashore to long and anxious waiting; the pasture lands provide a setting for treatment of infidelity; and the wasteland for a long separation.

The second major category is termed karu, lit. “things born” or “native”; this provides a framework in terms of concrete representations of the five major themes (phases of love, physiographic regions). There is, first, the basic division into Gods and Nature. Nature is subdivided into Human and Non-human nature. Under human beings, the tribes and their chieftains are treated, and also the occupations, arts, ways of life, customs, musical instruments etc. Non-human nature is animate and inanimate: the two main representatives of animate nature are birds and beasts; while under inanimate nature are described the typical trees, flowers, objects, forms of water (whether a mountain-rivulet, a broad river, the sea, ponds, waterfalls) etc.

Finally, the third major category is termed uri, lit. the “proper, specific” aspect, that is the essence of poetry; this deals with the innermost psychological events, with the drama of human souls and hearts; this is the inner and external life, the behaviour of the heroes, their feelings, deeds and situations.

We will deal in some detail with the three categories of mutal, karu and uri. The first division of the space-time continuum, as just indicated, concerns the appropriate time of an event. There are six seasons, six major times of the year:

- kār or the rainy season (approx. August-September);

- kūtir or Winter (October-November);

- muṉpaṉi or “early dew”; (December-January);

- piṉpaṉi or “late dew”; (February-March);

- iḷavēṉil or the season of “young warmth” (April-May);

- mutirvēṉil or the season of “ripe heat” (June-July).

There are also six minor times of day and night (six by four hours): dawn, sunrise, midday, sunset, nightfall, dead of night. These categories provide for the space-time coordinates of an event of love.

Table 6.1 gives the phases of love corresponding to the six types of landscape: union of lovers and immediate consummation corresponds to the hills; domestic life and patient waiting of the wife is described under mullai or forest (and pastures); anxiety and impatient waiting under neytal or seashore; infidelity of the man under marutam or agricultural tracts; and elopement and separation under pālai or wasteland.

Phases of love in correspondence to the landscapes

| Phase of love | Landscape |

|---|---|

| Union of lovers | Kuṟiñci - hills |

| Domesticity Patient waiting |

Mullai - Forests |

| Lover’s infdelity Sulking scenes |

Marutam - Cultivated Fields |

| Separation Anxious waiting |

Neytal - Sea-coast |

| Elopement Hardships Separation from lover or parents |

Pālai - Wasteland |

As we may see, considering both kaḷavu and kaṟpu, pre-marital and wedded (plus extramarital) love, and both well-matched and ill-matched union, the theory provides for a minute description of the entire gamut of human erotic experience, for the total love-experience of man and woman. This I think is very unique and extremely interesting. A pertinent question may be asked at this point: what about the corpus of the texts themselves? Did they really describe all these situations? The answer—probably surprisingly—is positive. Indeed they did. There was probably an evolution in this literature: it seems that the oldest poems could be classed under kuṟiñci and pālai, i.e. dealing with the immediate erotic union and with the elopement of the girl; while the two tiṇais dealing with ill-matched union seem to be later additions: not additions of the theoreticians, though, in search of pedantic completion, but the texts themselves, dealing with these aspects of human love, seem to be later, as we shall see.

The earliest, most comprehensive and elegant description of these concrete representations of the five tiṇais is given by Nakkīrar in his Commentary on just two words of the 1st sūtram of Iṟaiyaṉār’s Akapporuḷ (aṉpiṉ aintiṇai “the five situations of love”). He bases his exposé on tradition and on the TP which he quotes whenever necessary. After an engaging and charming discussion of what is aṉpu “love” (ed. 1939, pp. 18-20), Nakkīrar asks: “What does aintiṇai mean?” And his answer to this question is a brilliant treatment of the theory of the five physiographic regions and the five basic love-situations.

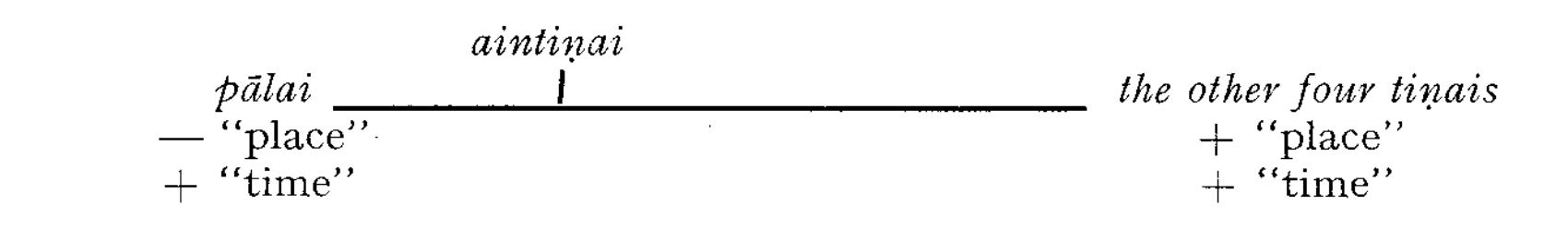

First he gives the five terms in the order kuṟiñci, neytal, pālai, mullai, marutam (quoting TP 3); he adds at once that these five are discussed in terms of mutal, karu and uri. Mutaṟporuḷ is of two kinds: place and time (TP 4). According to Nakkīrar, however, pālai or the “separation” situation has no proper place (nilam) corresponding to it. Presenting the mutal once more schematically and in accordance with Nakkīrar, we get the following charts:

| tiṇai (“situation”) | place | time |

|---|---|---|

| pālai | noon; hot season; also “late dew” | |

| kuṟiñci | mountainous region | dead of night; cold season; also “early dew” |

| neytal | sea-shore | sunrise |

| mullai | forest | rainy season; evening |

| marutam | cultivated fields | dawn |

For confirmation, Nakkīrar quotes TP 5-10 and adds that all the six seasons of the year must be appropriate to marutam and neytal, since no particular seasons are mentioned.

Nakkīrar gives then a detailed list of concrete natural representations (karu). Karu, he says (quoting TP 18 as authority), is “god, food, beast, tree, bird, drum, occupation, lyre and other items”.

Ideally, the kuṟiñci or mountainous region has Murukavēḷ as its god, its food is the five varieties of paddy and millet, the beasts are the tiger (panther), wild hog and elephant; the trees: eagle-wood, ebony, Pterocarpus marsupium, teak and the kino tree; typical birds are the parrot and the peacock; drums of three kinds: veṟiyāṭṭuppaṟai (drums used by Murukaṉ‘s priests), large drums (toṇṭakam) and kuravai (hunters’ drums). Typical activity of the inhabitants: gathering honey, digging up edible roots, dancing and/or wandering about the hills, and driving away parrots from millet-fields. The particular lyre (or harp), yāl, is called “mountain-lyre”. Under “other items”, Nakkīrar understands the name of the hero,6 in our case cilampaṉ, veṟpaṉ, poruppaṉ;7 the name of the heroine, koṭicci or kuṟatti;8 the typical waters—water-falls and mountain springs; human settlements: small hamlets and kuṟicci (“village”, DED 1534). Flowers: conehead (kuriñci, Strobilanthes), glory lily (Gloriosa superba), kino (Terminalia tomentosa) and water-lily (Pontederia); and, finally, the name of the people is kuṟavar, iṟavuḷar, kuṉṟavar.9

6 The literary hero is called kiḻavōṉ, lit. “old man” (DED 1315), also “headman, chief” or talaivaṉ (DED 2529) “chief, headman, lord”; the heroine kiḻavi, kiḻavōḷ or talaivi.

7 cilampan (?< Skt. or Pkt.) “hillman; chief of the hill tribe”; poruppaṉ “chief of the hill-tribe”; veṟpaṉ “id.”.

8 koṭicci (? DED 1704) “woman of the hill-tribe”; kuṟatti (cf. DED 1530 for Dr. cognates) “woman of the hill-tribe, woman of the Kuṟava tribe”.

9 kuṟavar (DED 1530); kuṉṟavar (DED 1548) “hillmen, mountaineers” iṟavuḷar (DED 442) “hill tribes”.

10 tuṟaivaṉ “he of the harbour; lord of the harbour” (DED 2773); koṇkaṉ lit. “husband, man”, cērppaṉ (cf. cērppu “sea-coast”) “he of the sea-coast; chief of the sea-coast”.

11 nuļai “fishermen-tribe, fishermen-caste”; nuḷaicci “she of the fishermentribe”; paratti “id.”.

12 E.g. Kāvirippaṭṭiṉam, lit. “the harbour-town on the Kaviri”, the famous sea-port of early Cholas. DED 3199.

13 DED 3332 “seaside village, town, village”. Preserved in the modern names of several quarters of Madras (Kīḻpākkam = Kilpauk, Nungambakkam etc.).

14 Cf. DED 3263. ? Skt bharata- “barbarian”. To this day, the fishermen of Madras sea-coast are called Paratavar.

In the sea-shore regions, neytal, Varuņaṉ is the patron-deity; for livelihood, people sell fish and salt; typical beasts are the shark and the crocodile; trees: mast-wood and Cassia sophora; as birds, Nakkīrar gives the swan, the anril (= cakravāka) and makanril (? a water-bird); as drum, “the drum of fish-caught”, and “the boat-drum”. The inhabitants are engaged in selling fish and salt, and in production of salt. The lyre is called viḷari (?“youth”). The names of the hero are tuṟaivaṉ, koṇkaṉ, cērppaṉ;10 of the heroine, nuḷaicci and paratti;11 the characteristic waters are the sand-well and brackish marshes; the flowers: white-petalled fragrant screwpine (Pandanus odoratissimus) and white water-lily (Nymphaea lotus alba); as the typical settlements, the commentary gives paṭṭiṉam12 (“maritime town, harbour-town”) where “ships enter”, small hamlets and pākkam;13 the name of the people is paratar14 (fem. parattiyar) and nuḷaiyar (fem. nuḷaicciyar).

Pālai, “waste-land”: according to Tolk., there is no deity to pālai, “since there is no nilam (pālai is a ‘situation’, not a ‘place’)”; but others give Bhagavatī (Durgā) and Āditya (Sun-god). Food: whatever was gained by high-way robbery and plundering. Beasts: emaciated elephant, panther, wild dog (Canis dukhunensis); trees: mahua (Bassia longifolia) and ōmai “the tooth-brush tree”; birds: vulture, kite and pigeon. Occupation: highway robbery, murder, stealing. Melody type: curam. The term used for the hero: mīḷi “warrior” (lit. “the strong one, the valiant man, the fighter”, used also for the God of Death); viṭalai “young hero” (lit. “young bull”), kālai “warrior” (or “bull, steer”?). The heroine called eyiṟṟi “woman of the Eyiṉar tribe” or pētai “the naive one” (lit. “girl between 5 and 7 years of age”, “simple woman”). Flowers: kurā (Verberia corymbosa), marā (Barringtonia acutangula or Anthocephalus cadamba), trumpet-flower (Stereospermum chelonoides, suaveolens, xylocarpum). Waters: dry wells, dry ponds. The name of the inhabitants is eyiṉar (fem. eyiṟṟiyar) and maṟavar (fem. maṟattiyar).15 The villages are called kolkuṟumpu.16

15 Connected for sure with DED 691 ey “to discharge arrows, n. arrow”; eyiṉar “arrow-men, hunters”. Maṟavar (cf. DED 3900 maṟam “valour, anger, war, killing”) “hunters, people of Marava caste”; they were a rather prominent community in historical times in Tamilnad. The caste exists until today, chiefly in South-East Tamilnad (Ramnad).

16 Connected prob. with DED 1542 “stronghold, fort” or DED 1541 “battle, war”, and with DED 1772 “killing”.

17 iṭai (DED 382) “the herdsmen caste”. āyar: DED* 283; āy “the cowherd caste”, ā “female of ox, sambur and buffalo”.

The god of mullai “forest” is Vāsudeva; the food—common millet (varaku) and cāmai (?); typical beasts—hare and small deer; trees: koṉṟai (Cassia fistula) and kuruntu (wild lime, Atalatia); birds: jungle-fowl, peacock, partridge. Drums: “bull-taking drum” and the muracu. Activities of the people: weeding of millet-fields, harvesting of millet, threshing of millet, grazing of cow-herds, “taking of bulls”. The melody-type: mullai. The name of the hero is the “lord (or inhabitant) of the land of low hills” (kuṟumpoṟainātaṉ). The name of the heroine—kiḻatti (lit. “mistress (of the house)” and maṉaivi “house-wife”. Flower: jasmine (Jasminum sambac, mullai) and Malabar glory lily (Gloriosa superba, tōṉṟi). Waters: forest-river. Settlements: pāṭi “town, city, hamlet, pastoral village” (DED 3347) and cēri “town, village, hamlet” (DED 1669). The name of the people: iṭaiyar (fem. iṭaicciyar) and āyar (fem. āycciyar).17

| Lover’s Union | Patient Waiting | Lover’s Unfaithfulness | Anxiety, Separation | Elopement, Separation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical flower (=name of region and poetic theme) | kuriñci | mullai | marutam | neytal | pālai |

| Landscape | mountains | forest, pasture | cultivated countryside | seashore | wasteland |

| Season | cold season, early frost | rainy season | all seasons | all seasons | summer, late dew |

| Time | night | evening | dawn | sunrise | midday |

| Hero | poruppaṉ, verpaṉ, cilampaṉ, nāṭaṉ | natan, tōṉral | ūran, makiḻnaṉ | cērppaṉ, pulampaṉ | viṭalai, kāḷai, mīḷi |

| Heroine | kuṟatti, koṭicci | maṉaivi, kiḻatti | kiḻatti, maṉaivi | nuḷaicci, paratti | eyiṟṟi |

| People | kuṟavar, kāṉavar | iṭaiyar, āyar | uḻavar, kaṭaiyar | nuḷaiyar, paratar, aḷavar | eyiṉar, maṟavar |

| Occupation | guarding millet fields, honey-gathering | pastoral occupation, fieldwork | agriculture | drying fish, selling salt | wayfarers, robbery, fighting |

| Pastimes | bathing in waterfalls and streams | bull-fight, kuravai dance | bathing in ponds, festivals, arts | bathing | dancing, fighting |

| Settlements | ciṟṟūr, ciṟukuṭi | ciṟṟūr, pāṭi | pērūr, mūtūr | pākkam, paṭṭiṉam | kuṟumpu |

| Waters | water-fall, hill-pond | pond, rivulet | river, pool, well | well, sea, salt-marshes | waterless well, stagnant water |

| Beasts | monkey, tiger, bear, elephant | deer, hare | buffalo, freshwater fish, otter | crocodile, shark | wild dog, tiger, lizard, elephant |

| Birds | peacock, parrot | jungle hen, sparrow | heron, stork, swan | sea-gull, marine crow | dove, eagle, kite, hawk |

| Trees | teak, sandal, bamboo, jack | koṉṟai, waterlily, red kāntaḷ, piṭavam | mango, lotus | puṉṉai, tāḻai-shrub, muṇṭakam, aṭampu | uliñai, ōmai, cactus |

| Food | millet, mountain-rice | varaku, tuvarai | rice | fish | |

| Instrument | toṇṭaka-drum, mountain-lute | ēṟṟu-drum, forest-lute | maṇa-drum, kiṇai, field-lute | pampai-drum, viḷari lute | uḷukkai-drum, desert-lute |

| Melody-type | kuriñcippaṇ | cātāri | marutappaṇ | cevvaḻi | curam |

| God | Murukaṉ | Māyōṉ (Tirumāl) | Intiraṉ | Varuṇaṉ | Koṟṟavai (Kāḷi) |

Note: kuṟiñci: conehead, Strobilanthes; various S. and Barleria species; said to grow at an altitude of 6000 ft. and flower only once in 12 years; flower is bluish. mullai: Jasminum sambac; Arabian jasmine. marutam: Terminalia tomentosa. neytal: white Indian water-lily, Nymphaea lotus alba; blue nelumbo. pālai: silvery-leaved ape-flower, Mimusops kauki; grows in barren tracts; is evergreen; blossoms small, white.

The god of marutam, cultivated fields, is Indra; for food, the people have rice (cultivating paddy of the two varieties, cennel and veṇṇel); typical beasts are the buffalo and the otter; trees: rattan (Calamus rotang), strychnine tree (Strychnos nux vomica) and marutu (Terminalia tomentosa). Birds: duck, heron. Drums are called maṇamuḻavu and nellari kiṇai.18 Occupation of the people: cultivating paddy. The lyre is called simply maruta lyre. The names of the hero are ūraṉ (lit. “villager, inhabitant of village, town”) and makiṇaṉ (“husband; chief of agricultural tract, lord”, DED 3768). The heroine is called kiḻatti or maṉaivi “house-wife”. Flowers: Lotus and red water-lily. Waters: wells in the houses, ponds and rivers. Settlements are termed pērūr, lit. “big village, big town”. The name of the inhabitants: kaṭaiyar (fem. kaṭaicciyar), uḻavar (fem. uḻattiyar).19

18 maṇamuḻavu, lit. “marriage-drum”; nellaṟi kiṇai, lit. prob. “paddyharvesting small drum”.

19 DED 929 kaṭaiyar “men of the lowest caste or status”; uḻavar (DED 592 uḻu “to plough”) “ploughmen, agriculturalists”.

Table 6.2 shows the various representations, the attributes of the five tiṇais, the elements of the karu-strata, how they are usually found in the texts.

Nakkīrar turns then his attention (pp. 24-25 ed. cit.) to the uripporuḷ, and, quoting TP 14, makes the following statement (cf. Table 6.1): sexual union (of lovers), puṇartal, is the kuriñci-phase (situation); separation, pirital, is the pālai-phase; waiting, iruttal, is the mullai-phase; anxiety, iraṅkal, is the neytal-phase; sulking, ūṭal, is the marutam-phase.

At the end of his discussion Nakkīrar refutes the one-sided conception of tiṇai as either “region” (nilam) or “situation” (oḻukkam, lit. “conventional rules of conduct”); tiṇai is not “either or” but “both”; Nakkīrar says it quite explicitly: tiṇai is both region and situation, “like the spot on which the light (cuṭar) of a viḷakku”lamp” falls, is also called viḷakku “light” (cf. DED 4524 viḷakku “lamp; light”).

It is obvious that not all clues of the karu-strata occur in a poem. They never occur in totality, they never could occur. But at least some of these characteristic representations, of these typical, diagnostic attributes do always occur. These clues are sometimes a part of the technique of “suggestion” called iṟaicci, and of the “implied simile” or “implied metaphor”, termed uḷḷuṟai uvamam (cf. TP 242 ff.).

iṟaicci (cf. TP 229), occurring usually, but not always, in the utterances of the heroine and of the heroine’s friend is “suggestion”, “implication” through the description of a natural phenomenon or event. Closely related but not identical is uḷḷurai uvamam or “implied metaphor”: objects of nature and their actions stand for the hero, the heroine and other humans and their actions. Nature is described and the listener (reader) should understand the implications of such natural descriptions: e.g. a buffalo treading on a lotus and feeding on tiny flowers implies the unfaithful lover who leaves the heroine and makes her suffer (“lotus”) while he “feeds” on harlots (“tiny flowers”). A heron eyeing the āral-fish, its prey (Kur. 25), stands for the lover who “takes” the heroine. The strongly erotic, even sexual imagery in Kur. 131 (the impatient hero = ploughman with his single plough “in haste to plough his vast virgin land fresh with the rains”, which symbolizes the woman) is quite obvious. In Kur. 40 there is a sexual image which is a perfect uḷḷurai uvamam: “waters of rain pouring down on red soil” (the hot, parched red soil waiting for rains stands quite obviously for the woman, while pouring rain symbolizes the man).

For iṟaicci or “suggestion” cf. e.g. Akam 360: therein, the hero comes to visit the woman frequently at daytime, and she requests him to come during nights: she describes the front yard of the house, adorned by puṉṉai trees with fragrant blossoms, and by palmyras with the nest of aṉṟil (= cakravāka) birds. The “suggestion” according to the commentary is that at night the aṉṟil birds, being close to the house, keep the woman awake by their heartrending cries, and she longs for her lover’s company; a “secondary” suggestion is involved: the urge on him to marry her as soon as possible.20

20 M. Varadarajan, “Literary Theories in Early Tamil-Eṭṭuttokai”, Proc. of the I Intern. Conf. of Tamil Studies Vol. 2, Kuala Lumpur (1969) 49.

In terms of sociological and psychological observations, one should probably stress the following facts: First of all, the heroes of these love-poems were by no means monogamous. This was almost taken for granted. Harlots, concubines and prostitutes play quite an important part in this literature: the marutam theme abounds in harlotry. Second: it is interesting, that out of the five major themes, actually four deal in this or that form with waiting: the two tiṇais appropriate for waiting par excellence are mullai—patient waiting—and neytal—long and anxious waiting for the hero to return. But pālai, wasteland, also deals with waiting and separation (apart from elopement); and so does marutam: here the wife is waiting till the debauchee returns from the harlot. Finally the kuṟiñci theme might be considered as an echo of the primitive, tribal, pre-nuptial promiscuity.

The second genre—puṟam—has, of course, its conventions, too. It also has its basic division into poetic situation and into themes. In dealing with the akam genre, we discussed the concepts of the poruḷ or poetic content, subject matter, and the tiṇai which may probably be translated best as the poetic situation. In a detailed discussion of the puṟam genre, yet another term must be introduced: tuṟai or theme.

| Akam | Uri | Puṟam | Uri | Features common to both | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | kuṟiñci | (first) union of lovers | veṭci | cattle-lifting, prelude to war | nighttime; hillside; clandestine affair |

| 2 | mullai | separation (patient waiting) | vañci | preparation for war | forest in the rainy season; separation from beloved ones |

| 3 | marutam | infidelity, conflict | uḻinai | siege | fertile area (village, town); at dawn; refusing entry |

| 4 | neytal | separation (anxious waiting) | tumpai | battle | seashore in akam = open battleground in puṟam; no particular season; evening; grief |

| 5 | pālai | elopement; search for eloped girl; search for wealth and fame | vākai | victory; an achievement | praise |

| 6 | peruntiṇai | mismatched love | kāñci | struggle for excellence; endurance | no landscape; struggle, defeat, note of sadness |

| 7 | kaikkiḷai | unrequited love | pāṭāṇ | elegy; asking for gifts; praise | no landscape; one-sided relationship; note of sadness |

It was stressed right at the beginning that all subject-matter of literature dealt either with emotional situations of love or with other situations than those of love, primarily with heroic situations. From Table 6.3 one sees clearly that there is an intimate connection between both genres, akam and puṟam; that, behind both, there is a unified perception and conception of the universe. I cannot agree with J. R. Marr’s (op. cit. p. 44) and Kailasapathy’s criticism (op. cit. p. 189) that the pairing of love and heroic situations appears artificial. Rather I would tend to agree with the medieval commentators like Nacciṉārkkiṉiyar who seem to have intuitively felt that there had existed a basic homogeneous and uniform conceptual pattern behind the classification of human situations into the two basic genres. According to Nacciṉārkkiṉiyar (TP 56), akam and puṟam are like the inner palm of the hand and its back.

The heroic situations are, too, described under 5 tiṇais:

veṭci(ttinai) is the prelude to war: this is the cattle-raid. The features which this situation has in common with its akam-counterpart, kuṟiñci, are the time: night, the place: a mountain-forest; and the fact that it is a clandestine affair, just like puṇartal or sexual union of lovers before marriage.

vañci is the preparation for war and the beginning of the invasion. Common features with its akam-counterpart, mullai: both take place in the rainy season and in the forest; both describe the separation from loved ones, and wifely patience, iruttal.

uḻiñai describes the siege of a settlement or fortress; like marutam, it takes place in an inhabited, fertile area (city etc.) at dawn; the infidelity results in akam in ūṭal, wifely sulking, and —both in love and war—in “refusing entry” (A. K. Ramanujan).

tumpai or pitched battle corresponds to neytal in akam: in both, there is anxiety, separation of wives from the heroes; the akam situation is set on the open sea-shore; the heroic situation, in the open battleground; evening and grief (iraṅkal) are common to both.

vākai describes victory, the ideals of achievement: its counterpart in the akam genre is pālai; both have in common the achievement of the hero: in one, the abduction and possession of the woman, or the search for wealth and fame; in the other, achieving wealth and fame in victory after long separation from the wife (pirital) in war.

In both categories, there are two situations which are not specifically related to any type of landscape; both are not supposed to be ideal topics for poets; both are considered to be so to say “abnormalities” in love-situation as well as in war-situation.

vāñci in the puṟam genre describes struggle for excellence, endurance, but also the feeling of transience of the world and defeat, death; in the akam genre, this corresponds to the peruntiṇai, struggle and defeat in the mismatched love.

pāṭāṇ is praise, or elegy, as well as asking for gifts in the heroic genre; this corresponds to kaikkiḷai, unreciprocated love, in akam; both have in common e.g. a one-sided relationship, a note of sadness etc.

Thus, for the old Tamil classical poet, there were fourteen basic human situations, suitable for poetic treatment, which were based on a unified conception of the universe, which comprised both the “numenon” and the “phenomenon”, and which, using the principle of economy and the technique of concentration, reflected the entire scale and spectre of human experience.

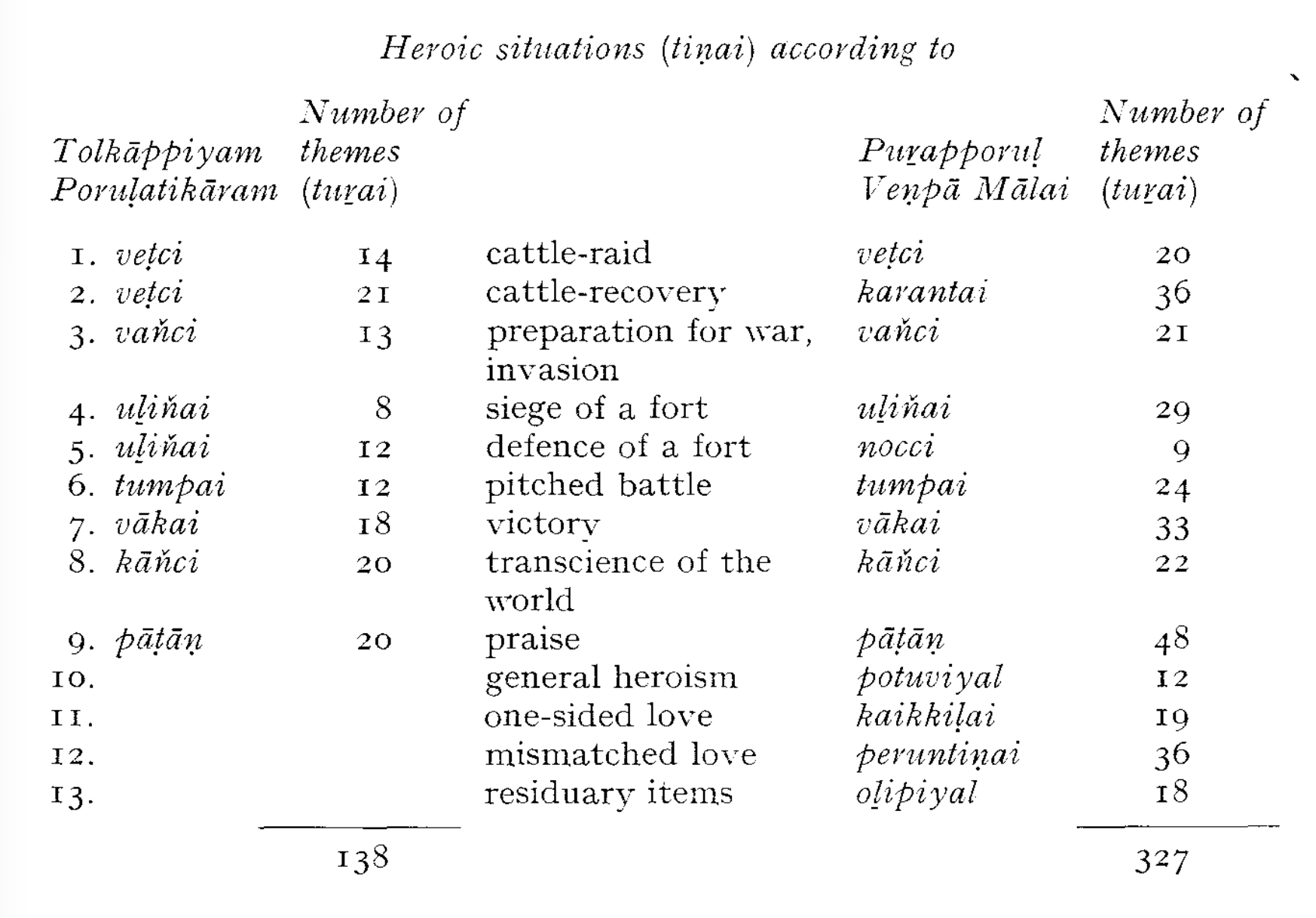

As may be seen from Figure 6.4, the later “grammar of heroic poetry”, Puṟapporuḷveṇpāmālai, follows a different and more elaborate scheme when compared to Tolk. Poruḷ. It enumerates twelve non-love situations in contrast to seven listed in TP. In this list are included the two abnormal love-situations; so that, essentially, there are 10 heroic situations according to PVM. The number of themes is also higher in PVM than in TP, as one would naturally expect.

The word for theme, tuṟai, means lit. “place, location, way, section; seaport, roadstead, frequented place” etc. (DED 2773). According to Pērāciriyar’s commentary, poruḷ or “general subject-matter” includes all subject-matter created by poets while tuṟai has a limited range and scope, being part and a section of poruḷ; according to Iḷampūraṇar, the best commentator on Tolk. (Poruḷ. s. 510), the description in a poem of people, animals, birds, trees, land, water, fire, air etc., that is pertinent to the seven major situations of love (akam tiṇai) and the seven major situations of heroism (puṟam tiṇai) should be in harmony and never contrary to tradition and convention; a clear and excellent exposition of such matters in a poem is called tuṟai. Nacciṉārkkiṉiyar says, using metaphor and analogy, that all sorts of matter become unified in the theme just like men, beasts and other beings drink water together from a river ghat (Tolk. Poruḷ. s. 56). According to Kailasapathy (op. cit. 192), tuṟai is the thematic clarity and unity in a poem: it should be specific and traditional: the definite theme in traditional poetry. And to the bards of the period, “the composition of a poem was equivalent to the composition of a theme” (192).

How does the “theme” work in the corpus of texts?

Let us take, as an example, the very first poem of Puṟanāṉūṟu (designated as Puṟ. 2 since Puṟ. 1 is the invocatory stanza). The colophon says: “tiṇai* (poetic situation): pāṭāṇ:”praise”; tuṟai (theme): ceviyarivuṟūu* “god counsel”; vāḻttiyalumām “or praise of qualities” sung by Muṭinākaṉār of Murañciyūr about Cēral king Utiyaṉ of Grand Feast”. Now in all the collections of bardic heroic poems that have reached us, each poem has a colophon which gives the situation (tiṇai) and theme (tuṟai). The entire corpus of bardic poetry seems to have been composed on the basis of definite themes. From the colophon quoted above we see that the tiṇai, the “situation” gives the more general, the major category, in this case, of pāṭāṇ or “praise”; the tuṟai or “theme” gives the minor, the more specific category: in this case a bard “counselling” a king on good conduct. There are eight poems treating the same tuṟai, theme, by eight bards, in the collection of Puṟam. Poems on love, akam, have, too, colophons with various degree of amount of information. Thus e.g. in Kuṟuntokai: the first poem, which belongs to the kuriñcittiṇai, has the following colophon: “tōḻi kaiyuṟai maṟuttatu, ‘the maid’s rejection of a present’. Tipputtōḷār (name of the poet).” “The maid’s rejection of a present” may be considered a theme, tuṟai.

This is not the place to give an exhaustive catalogue of all puṟam and akam themes. But some of them may be mentioned, to show how variegated and detailed the scale of experience, treated in those poems, indeed was. Here are some puṟam themes:

- nātu vāḻttu

- “blessing the country”: in praise of the wealth and beauty of the land of the hero, e.g. Patiṟṟup. 30.

- tumpaiyaravam

- “bustle of war”: a king distributing rewards to his soldiers after a victorious battle, e.g. Patiṟṟup. 34, 85.

- kāṭci vāḻttu

- “praise of a sight”: describes the reaction of seeing a great hero and a hero-stone (vīrakkal), e.g. Patiṟṟup. 41, 54, 61, 82, 90.

- oḷvāḷmālai

- warriors brandishing swords: the king, swinging shining blade, is joined in dance by warriors wearing anklets, cf. Patiṟṟup. 56.

- kuravai nilai

- kuravai dance of women; women joining warriors, holding hands, celebrating hero’s victory by dance.

- paricilviṭai

- “munificence”: a king bestowing gifts on his bards, e.g. Puṟ. 140, 152, 162, 397, 399.

- neṭumoḻi “vow”

- describes the vow of a warrior, cf. Puṟ. 298.

- āṉantap paiyuḷ

- theme describing the distress of a wife on her husband’s bereavement, e.g. Puṟ. 228-9, 246-7, 280.

Our choice of akam themes must of necessity be equally brief: e.g. “What the heroine said to her heart so that the companion heard it”, e.g. Kur. II.

“What the heroine said to her friend who was distressed thinking that she (the heroine) will be unable to bear it”: e.g. Kur. 12; and its sub-theme:

“What the heroine said to the friend who was in distress thinking that she will not endure the separation” (e.g. Kur. 4, 5).

“The promise of the friend to the heroine broken by the separation” (Kur. 59).

“The speech of the hero to the friend” (e.g. Kur. 136, 250).

“The fear of separation, expressed by the hero after sexual union” (e.g. Kur. 137).

“The friend refuses entry to the hero” (Kur. 258).

“The speech of the mother after the elopement of the daughter” (e.g. Kur. 396).

One concluding remark on the technique of description: The two typical features of the descriptive technique employed by early Tamil classical poets are terseness and concentration. The descriptions are intensive, never extensive; acute, accurate and sharp, never elaborate and full, never “from head to foot”.21 This technique gives no room for exaggeration, so typical of Sanskrit kavya poetry, and of later, medieval Tamil literature. The poets take their inspiration straight from nature and experience; in a way, they creatively copy nature and life. This means that they do not use foreign, borrowed imagery. The matter employed in descriptions is traditional and conventionalized (cf. next chapter for the detailed treatment of this feature). And, finally, there is usually a perfect harmony of content and its formal expression. M. Varadarajan quotes,22 as an example of a typical early classical description, Puṟam 334. 2: a hare is pictured as tūmayirk kuruntā ṇeṭuñcevik kuṟumuyal “small (young) hare with pure fur, short legs and long ears”. The poet (Maturai Tamiḻakkūttaṉār) has succeeded, using three simple adjectives and three simple nouns, to convey the picture of a hare in terms of the animal’s most typical features (so to say the essence and idea of “hareness”); it is simple and perfect, in one word, classical.

21 Cf. the medieval Tamil term kēcāti pāta varuṇaṉai “description from head to foot”.

22 in “Literary Theories in Early Tamil-Ettuttokai”, pp. 52-53.

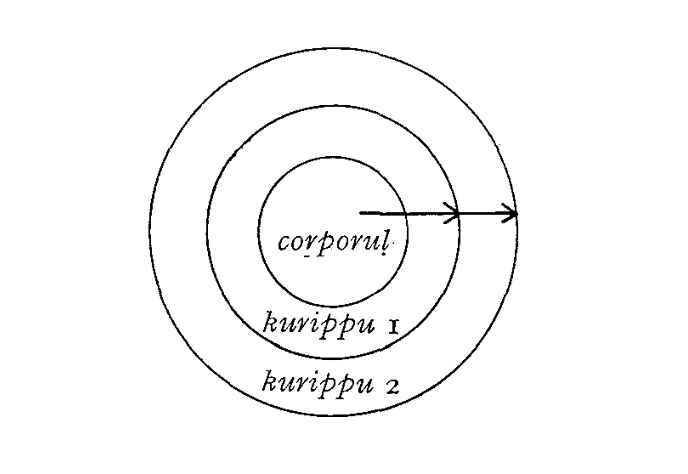

The technique of allegory (uḷḷurai uvamam) and especially the use of suggestion (iṟaicci), comparable to the Skt. vyañjanā, vyaṅgya- and termed uṭaṉuṟai by Tolk. (s. 1188) has reached its perfection in a number of stanzas where in fact at least three layers of meaning may be distinguished by a true connoisseur of sophisticated poetry. Thus a charming and seemingly simple stanza (taṉipāṭal) beginning in Ta. ellā utukkāṇ says:

Look

there

my lord

near that lovely pond

with its broad green lotus leaves

the heron

motionless and without fear

stands shining

like a white and golden

conch.

This stanza, a simple picture of a quiet scene, has three layers of meaning. The first “obvious” meaning “on the surface” (coṟporuḷ) is the one given in the inadequate translation above. However, the meaning of the crucial phrase, “the heron, standing motionless and without fear”, expands and transcends the obvious, because the pivotal expression in the poem, tuḷakkamil, “without agitation, fear and motion”, conveys a suggestion, an implication (kuṟippu) deriving from the “obvious” meaning: “there are no people at that place, it is deserted”. This kuṟippu, however, is the source of yet another expansion, into a further layer of meaning, an inference, a suggestion (kurippu2), a hint to the lover: since the place is quiet and deserted, it is an ideal spot for love-making (puṇarcci); so, let us go and make love. This, at least, is what the commentator and the scholiast has to say about the text, and we are fully entitled to agree that the implication and inference is not “read into” the stanza ex post but fully intended by the poet, since it follows certain patterns of convention, and since there is a unanimous and traditional agreement in its interpretation.