16 The Prose Of The Commentators

“Like the oil pressed out of sesamum-seed, so grammar derives from literature”.

The primacy of literature before grammar was mentioned in our discussion of the Tolkāppiyam. Analogically, before there was a commentary, urai, there must have been the original text, mūlam. Although, according to Pērāciriyar (13th Cent. A.D.), there had been a time when there were no commentaries, and literary works were easily understood by everyone,1 it seems nowadays almost unbelievable that there could have been such a golden age. We can hardly imagine a classical text without a commentary. And there are texts to which the commentaries are considered decidedly more important and relevant than the text itself.2

1 Tolk. Marapiyal ss. 98, 101, Pērāciriyar’s comm.

2 E.g. Nakkīrar’s celebrated commentary to Iṟaiyaṉār Akapporuḷ alias Kaḷaviyal.

3 Cf. Pāratitācan (Bharatidasan) Kavitaikal, 2nd vol., containing a “verse-commentary” on some Kuṟuntokai poems, and Kannadasan’s poetic comments upon Muttoḷḷāyiram.

4 For the etymology of the two basic terms: mūlam < Sanskr. mūla- “root, base, fundament, basic, original text”; urai (Dr. ?) “word, speech; word of praise; comment, commentary; to say, speak, utter, comment”.

Although there exists a limited number of commentaries in verse in Tamil, this is not typical.[^commentaries-in-verse-not-typical] And yet, for the development of Tamil literature, it is important that some modern poets, notably Bharatidasan and Kannadasan, composed a few works as “commentaries” in verse upon ancient classical texts.3 But, generally speaking, it is the prose-commentaries one usually has in mind when discussing the important cultural phenomenon which is called urai.4 s [^commentaries-in-verse-not-typical]: Cf. U. Vē. Cāminātaiyar, Tiruvalluvarum tirukkuralum, 8.

I speak about a ‘cultural phenomenon’ on purpose. The existence of a live commentatorial tradition, and the origin and development of a rich commentatorial literature, presuppose a specific cultural atmosphere and a certain outlook which may be characterized in terms of a number of more or less well-defined, constituent elements like “return to classicism”, “unquestioned authority of the original text”, “initiatory structure of learning”, “urge toward ratiocination, intellection and learned classification for their own sake”, “positive, appreciative criticism”; and, basically, the concept of the division of the totality of recorded literature into underlying texts (mūlam) and comments upon them (urai).5 These conditions were prevalent in a high degree in Tamilnad between the 12th-16th centuries, but especially in the 13th-15th centuries, the “golden age” of the commentators. There was a definite “return to classicism” (to the great classical literature of the “Caṅkam” and post-“Caṅkam” epoch) in the works of such men as Parimēlaḻakar (14th Cent.),6 the authority of the original text went unquestioned, and hence the criticism of the commentator was always positive and appreciative: the commentator paraphrased, analysed, explained the meaning of the original text (quite often misunderstanding the original author), questioning or even refuting the views of other commentators, but never the views of the original author; for the entire recorded literature was divided into the mūlam,* the original texts,”revealed” by sage-poets or by poets revered and respected because they were ancient and aged, and urai,* the prosaic commentaries where disagreement and polemics were quite welcome; finally, there was the tendency to systematize, to be as exhaustive and as explicit as possible; reading became study.

5 It is significant that, in this respect, the bhakti hymns, especially Śaiva bhakti literature, were not considered “literature”: they were not supposed to be commented upon; there was a sort of tabu on any commenting upon these hymns.

6 Cf. S. Vaiyapuri Pillai, Tamiḻc cuṭar maṇikaḷ, p. 198.

The earliest commentaries, however, were obviously brief answers to students’ questions concerning isolated items: obscure, unintelligible words and difficult grammatical forms, technical terms, allusions to historical events, etc. Some of such old commentaries (or fragments of such commentaries) have actually been preserved, and later commentaries, modelled upon these, are in existence. They are characteristic for their brevity, terseness, economy of language and style. Sometimes such commentaries are hardly more than collections of annotations and remarks, as e.g. an old anonymous commentary to 90 poems of Akanāṉūṟu. Such collections of annotations were appended to (and in modern times printed along with) the original text under the term kuṟippurai or “annotations” (lit. “note-commentaries”).

Somewhat more explicit and detailed commentaries (like the old anonymous commentary to Puṟanāṉūṟu or Parimēlaḻakar’s commenry on Paripāṭal) are called poḻippurai or “abstracts”, “summaries”.

In course of time, commentaries became more involved and intricate, their form developed with the growth of ideas and the emergence of critical and polemic approach toward the opinions of former generations of scholars, and finally, after the texts were recorded in writing, much more complicated patterns evolved, including quotations of a number of examples, polemic passages, etc. These detailed, complicated commentaries are termed virivurai or viritturai, “detailed commentaries, dissertations”, and viḷakkurai, viḷakkavurai, “exemplifying commentary”.

There can be hardly any doubt that, originally, commentaries were transmitted orally in the same way as the underlying literary texts. This fact is explicitly mentioned e.g. in the famous commentary of Nakkīrar (8th Cent. A.D.) to Iṟaiyaṉār Akapporuḷ. It says: iṉi urai naṭantu vantavāṟu collutum “Now we shall reveal the way (āṟu) how the commentary came down [to us] (naṭantu vanta)”; and it goes on to report how the commentary passed from Nakkīrar to his son, etc., and how, finally, after having passed through eight generations of scholiasts, it was finally fixed by a Nilakaṇṭan of Muciṟi.

The origin of the commentaries may be sought in discourses between the teachers and the students, in other words, in the initiatory and personal structure of learning. There are many commentaries which still retain the character of viṉāviṭai—“questitions (and) answers”. In most commentaries, statements are interrupted with brief questions like eṉṉai “what?” or atu eṅṅaṉam “How is that?” Many statements are introduced with phrases like aẖtu eṅṅaṉam eṉiṉ, lit. “if you say how is that” or iccūttiram eṉṉutaliṟṟō veṉiṉ “if you ask whether this is what this sūtra says”, which show that such statements are in fact answers to questions. Such phrases became established and recurrent formulae in course of time.

As time went by, the great classical commentaries became in part unintelligible. Thus a need arose to comment upon them, and the super-commentaries or commentaries on commentaries (uraikkurai) were born. A typical case is, e.g., that of the great commentary of Parimēlaḻakar on the “Sacred Kuṟaḷ”. In the 17th Century, T. Irattiņa Kavirāyar composed a commentary to Parimēlaḻakar’s commentary (called Nuṇporuḷ mālai). Another super-commentary was written in 1869, and another in 1885 (by Murugesa Mudaliar). We have, in addition, five other modern commentaries which comment upon Parimēlaḻakar’s classical work.

The function of a commentary should, ideally—according to the traditional view—be,

to split and dissect, analyze and examine the text word by word and to give, in paraphrase, the meaning of each item in the text;

to quote examples and illustrations; and parallel loci from other texts;

to discuss, in form of questions and answers, the merits and demerits of other opinions.

In actual practice, there are not many commentaries which attain such perfection.7 But, according to an old stanza, a commentary should be a tool as useful to the student as “a style is to the goldsmith”, “a rod to the carpenter”; and as sharp as “a diamond needle”.

7 As illustration of a medieval commentary, the Appendix to this chapter gives a very brief segment of Aṭiyārkkunallār’s classical commentary to the Cilappatikāram.

There are many kinds of commentaries, the classification based usually on the exhaustiveness and expliciteness of the commentary, or on the various aspects on which this or that commentary concentrates. It seems that from the earliest times (i.e. from the age of the earliest extant recorded commentary, Nakkīrar on Iṟaiyaṉār Kaḷaviyal, 8th Cent. A.D.), four types of commentaries were distinguished:

- karutturai: should reflect and explain the sense of the text (karuttu = “thought: sense”);

- kanṇaḻitturai: should split the utterances into constituent words and give the gloss for each word (kaṇṇaḻivu is the terminus technicus for the process of “dissolving” the sandhi—the syntactophonemic and morphophonemic rules—and splitting up a stretch of text into isolated words); also termed patavurai, lit. “word-commentary”;

- poḻippurai, the abstract, the summary of the text (poḻippu, “compendium, digest, synopsis”); also termed muṭipu, “summary”);

- akalavurai or akalam: the detailed and elaborate exposition with examples and discussions (akalam, lit. “breadth, width”).

The best commentaries usually combine all these aspects and procedures. Thus e.g. U. V. Cuvāminātaiyar’s Commentary on Kuṟuntokai (1937) proceeds along the following scheme: 1) varia lectiones (textual variations, piratipētam, abbreviation p-m); 2) “word-commentary” (patavurai) ;3) summary (muṭipu); 4) basic sense, basic idea (karuttu); 5) detailed exposition (vicēṭavurai) including parallelisms and concordances.

Later, many sub-types of commentaries were added, so that e.g. the medieval grammar Vīracōliyam (11th Cent. A.D.) enumerates 14 kinds of commentaries.

A special kind of commentary is the arumpatavurai or “glossary (of unusual, rare terms)”.

There is another and very basic classification of the commentaries8 or rather of the entire expository and exegetic literature into

8 Cf. Naṉṉūl, Potuppāyiram 21-22.

kāṇṭikai, which paraphrases the text, explains the meaning of the original (usually in form of questions and answers), and gives illustrations, and

virutti, which, in addition to the functions mentioned above, critically evaluates other commentaries, engages in discussion, and supplements the text with its own data.

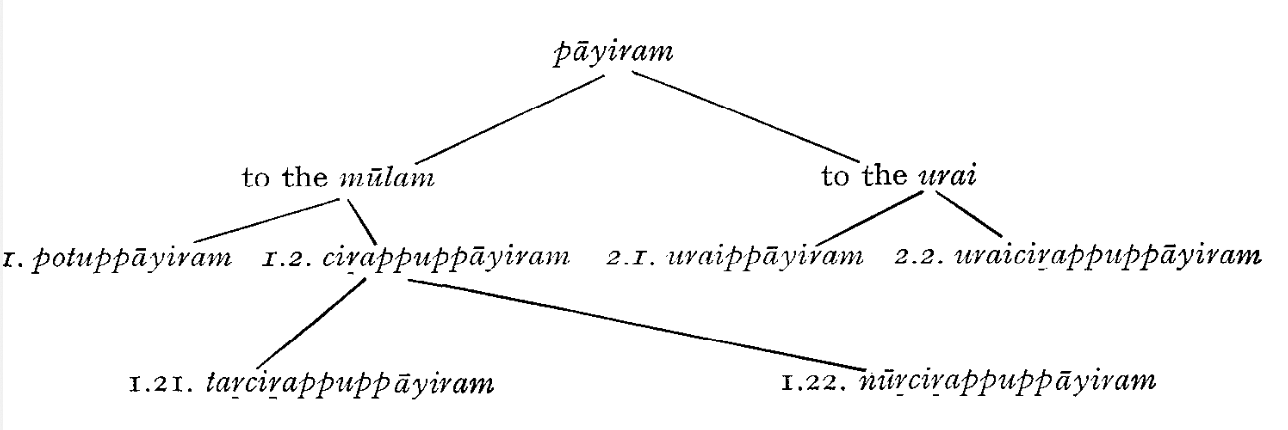

The prefatory verses—pāyiram (or puṟavurai)—to a work can also be considered as a sort of commentary since they provide information (usually embodying current oral tradition) about the author’s name, origin, education and learning, about his patron, etc.9 There are two basic types of prefatory verses: the potu pāyiram, “general preface”, and the ciṟappu pāyiram, “specific preface”. Later, however, there was some development in this genre, too, and the late medieval state of affairs may be symbolized by the following diagram:

9 It should also give the title of the book and explain it. Traditionally, a book should be entitled in either of the following five manners: 1. according to its author, e.g. Akattiyam (written by Agastya); 2. according to its patron (e.g. Iḷantiraiyam); 3. according to its size and/or the number of its parts (e.g. Paṉṉirupaṭalam, lit. “12 chapters”); 4. according to its content and importance (e.g. Kaḷaviyal “The Treatise on Secret Love”); 5. by an “arbitrary” or “primitive” descriptive term (e.g. Nikaṇṭu “Dictionary”).

1.1. —general preface (invocatory verses, in praise of a deity, in praise of Tamil, etc.), not dealing specifically with the work.

1.2. —specific preface concerning the work.

1.21. —subjective assessment of the work; expresses the attitude of the author toward the work and provides information about the author.

1.22. —objective assessment of the work; dealing with the excellence of the work; usually in verse.

2.1. —composed as a preface to the book by the commentator.

2.2. —dealing with the excellence of the commentary and the praise of the commentator; usually in verse.

By the time of the standard medieval Tamil grammar Naṉṉūl (lit. “The Good Book”, beginning of 12th Cent.), a more or less fixed and rather elaborate conception how an expository book (nūl) should look like had developed, and is formulated by the author of the grammar, Pavaṇanti:

It must have two prefaces, the “general preface” and the “specific preface” (aphorisms 1-3).

It must have a place in one of the three orders of a literary work, the primary, original (mutal), the deductive, derived (vaḻi), the supporting or supplemental (puṭai, cārpu) (5-8).

It must be advantageous for the reader in his quest after one or the other of the four grand objects—virtue, wealth, pleasure or deliverance (9).

It must agree with one or more of the 7 principles of authorship (10).

It must avoid the ten basic faults: to say too little, to say too much, tautology, contradiction, employment of inappropriate terms, mystification, to begin with another subject, to introduce another subject, gradual loss of vigour and tone, useless verbosity (11).

It must possess the ten beauties: brevity, elucidative power, sweetness, juncture of well-chosen words, rhythm, comprehensiveness of language, orderly arrangement, congruity, usefullness, clarity (12).

It must possess the 32 niceties (utti) (13).

It must be composed in terms of ōttu (section), paṭalam (chapter) and cuttiram (sūtra, aphorism). An aphorism of expository literature must follow another aphorism in regular and natural order like the flow of a river; it must have “lion’s look” (i.e. “look” forward and backward); it must “leap with ease like a frog”; and it must grasp its subject as a hawk grasps its prey (15-18).

Finally, it is proper that it has commentaries (20-22).

From the point of view of this particular book, the main importance of the commentaries lies in the fact that they represent long stretches of prose-writing, reflecting the evolution of standard literary Tamil prose10 in the course of an entire millennium. However, apart from the tremendous role they played in the origin and devellopment of Tamil prose, the commentaries are of paramount importance in many other ways.

10 Here we should add: of one particular style, the exegetic, expository style.

We know of the existence of a number of Tamil literary works only from the data provided by commentaries. They have preserved names of writers and titles of works which have otherwise got lost. More important than that, the commentators, in giving illustrations and examples, have preserved a number of verses and lines of lost works, or stray individual poems (taṉipāṭal) which would have otherwise never reached us. Of particular interest and import is the fact that they have conserved folklore material (tales, proverbs, even folksongs). A wealth of cultural and sociological material has also been amassed by the commentators.

The commentaries have also great value for the historical linguist, reflecting the development of the language of a particular type— the expository style of Standard Tamil—through almost ten centuries. And there is of course their primary function: to comment upon the original texts.

The prose of the commentators has always been a powerful accumulator which could be utilized and resorted to by the “makers of modern Tamil”. There is, in fact, a direct connection between the great medieval commentators and the makers of modern Tamil. Many of the prose writers of the 18th and 19th Centuries were, at the same time, scholars, editors, and commentators themselves and as direct heirs of the medieval commentatorial and scholastic tradition, they themselves wrote important commentaries: foremost among those who were, on the one hand, responsible for the creation of modern Tamil prose—fiction and non-fiction—and, on the other hand, composed, themselves, valuable commentaries, based in structure, language and style—on the classical medieval works, were Āṟumuka Nāvalar of Jaffna (1822-1876), the great editor Dr. U. V. Cuvāminātaiyar (1855-1942), the great purist Maṟai Malai Aṭikaḷ (1876-1950), and the many-sided Tiru. Vi. Kalyāṇacuntara Mutaliyār (1883-1953).

The first full-fledged commentary which has come down to us is Nakkīrar’s commentary on Iṟaiyaṉār’s Akapporuḷ (alias Kaḷaviyal). It probably belongs to the 8th Cent. A.D., but its final shape may be later.11 It is so very important because it consists of pages and pages of prose, which seems to grow, quite organically, out of the most popular classical Tamil metre, the akaval (āciriyam). “One little verse of the grammarian is dragged out through a wilderness of ornate, at times, poetic prose … Simile and metaphor illuminate his style, but clarity and simplicity, essential features of good prose, are absent”.12

11 According to S. Vaiyapuri Pillai, Kāviyakālam (1957), 215-16, in its present form the work is indebted to Cīvakacintāmaṇi, and hence could not have been prior to the 10th-11th Cent. A.D. The lower limit, in any case, is provided by the fact that the commentary quotes 325 poems from the Pāṇṭikkōvai, a work of probably late 7th Cent. which praises the Pāņṭiya king Neṭumāṟan (640-670 A.D.). Hence, Nakkīrar’s commentary cannot be earlier that the 7th Cent. On the other hand, it is older than Iḷampūraṇar. Late 7th-8th Cent. A.D. seems to be a reasonable estimate for the original text of the commentary, at least as far as our knowledge goes. Later careful investigation of the text can fix a more precise date. The final shape of the commentary may be later: 10th-11th Cent. A.D.

12 C. and J. Jesudasan, History of Tamil Literature, 196-7.

13 He calls it oru ciṟanta urainaṭainūl, “an outstanding prosaic work”. In Niṅkaḷum cuvaiyuṅkaḷ (1954), 195-6.

14 Nakkīrar’s commentary: innūl ceytār yārō eṉiṉ, māl varai puraiyum māṭakkūṭal ālavāyiṟ pal purai pacuṅkatirk kuḻavittiṅkaḷaik kuṟuṅkaṇṇiyāka uṭaiya aḻalavir cōti arumaṟaik kaṭavuḷ eṉpatu (ed. 1939, p. 3).

I am afraid I can hardly agree with this judgement. It is true that Nakkīrar’s prose is ornate, “poetic”, full of similes and metaphors. But it is also very plastic, colourful, lively, and not too involved, really. It is of course full of alliterations and assonances, and T. P. Meenakshisundaran calls it pāṭṭunaṭai “singing, melodic prose”. But this “melodiousness” and “ornateness” constitutes the excellence of the commentary, not its drawback. T. P. Meenakshisundaran obviously considers Nakkīrar’s commentary an admirable piece of prose, and I quite agree with his evaluation.13 It seems that Nakkīrar, while composing his melodious, singing, ornate, alliterative utterances, actually heard the rhythm of akaval (a metre which he must have known extremely well) and listened attentively to the akaval ōcai, the “narrative musical tone” of that metre. For this is precisely the rhythm of his prose. M. V. Aravintan, the author of an excellent book in Tamil called Uraiyāciriyarkaḷ, “Commentators” (Madras, 1968), gives an illustration which shows how very much is, in its structure, Nakkīrar’s prose “akaval-like”.14

One of the great qualities of this commentary is its liveliness, the fact that it is not at all pedantic, not at all dry; we do not find in it those endlessly involved complex sentences where we lose our breath in the search for a finite verb, stumbling across innumerable boulders of absolutives—constructions which are so cherished by some of the medieval commentators. On the contrary: Nakkīrar’s utterances are comparatively short, well-built, balanced; and in a particularly effective way he knows how to use the combination of a finite verb form (at the end of an utterance) and an absolutive or a participle (at the beginning of the next utterance). For all commentators, analogy is the most frequently used weapon. Nakkīrar is no exception; and his prose abounds in similes, some of them striking, some of them extremely pleasing. He is a shrewd observer, he is open-minded; his eyes, too, are open and see clearly and sharply the real world around him. He quotes a number of classical poems, known to us from the anthologies. Sometimes, he quotes poems which we do not know from any other source.

If there is a difference between this commentary and all other later commentaries, it is in the fact that Nakkīrar’s work is not so much a piece of expository and eruditory literature as rather a “poem in prose”. It lacks the deep scholarship, the searching intellectualism, the argumentative, even polemic tone—and also the insolence, pedantism, and errors of later commentaries.

There are a few truly great pages and paragraphs in this commentary. One of them is e.g. in praise of aṉpu, “affection, love”; the loving person’s characteristic features are “to die with the dying, to suffer with the suffering, to give generously, to speak sweet and gentle words, to love ardently in union and to pine anxiously in separation”. The lover should be “wise, faithful, understanding and resolute”; the woman should be “modest, shy, timid and virtuous”. Or consider the following similes: “like the sandal-tree, standing scorched and fading in the summer-heat, when it sprouts again after it received rain” (cūttirai 3); or this striking one: “she became pale and her heart melted and thawed like a wax-figure placed before glowing flame, like a dimmed, blurred reflection when one blows on the surface of a mirror…”.

While the underlying text may be superior to the commentary15 (though I doubt it), I think that Tamil was rather fortunate to have this magnificent piece of prose at the very source of its prosaic literary tradition sometime in the 8th Cent. A.D.

15 C. and H. Jesudasan, op. cit. p. 196.

16 M. V. Aravintan, uraiyāciriyarkaḷ (1968), p. 50.

Iḷampūraṇar wrote a commentary on the Tolkāppiyam some time in the 11th-12th Century. His style was compared to a “quietly flowing deep river”.16 It is clear and simple. The sentences are not too involved, comprising usually one, two, three clauses at most; the choice of words very well-balanced; and though he is not a purist, there are comparatively very few Sanskrit loanwords. If I should point to a model for polished interpretative, expository style in Tamil, Iḷampūraṇar would be undoubtedly the best choice. Cēṉāvaraiyar (13th Cent.), another commentator on the ancient grammar, is more elegant, more descriptive, his syntax is more involved and complicated, and he displays his Sanskrit knowledge.

Pērāciriyar (13th Cent.) is one of the great masters of Tamil prese. According to V. V. S. Aiyar,17 “his style is grammatical, graphic and simple. This is the best specimen of elegant and simple prose”. T. P. Meenakshisundaran finds his style “dignified”. I have to admire, above all, Pērāciriyar’s ability to attune the style of his writing to the diction and style of the mūlam, of the underlying text he was commenting upon. In the commentary to Tolkāppiyam, his style is terse, elegant, sharp, well-chiselled; however, in the commentary to Māṇikkavācakar’s Tirukkōvaiyār, it is mellow, sweet, melodious, and at the same time, admirably simple.

17 Tamil—the Language and Literature, ed. 1950, 4.

Aṭiyārkkunallār’s commentary on the “Lay of the Anklet” is above all a mine of information and data, including some about a number of literary works now lost. However, his sentences are complex, long and broad, epic in character. His style is very high and learned. Occasionally, his commentary reads itself like a learned epic poem.

Parimēlaḻakar (2nd half of the 13th—1st half of the 14th Cent.), a Brahmin of Kāñcipuram, is considered by many the “prince” of Tamil commentators. According to V. V. S. Aiyar (op. cit. 42), “his prose is very terse and in some places too brief to be easily intelligible … Like the style of the great poet whose work he had taken to annotate, his style also is so much compressed in form that no word in a sentence can be removed or substituted without at the same time damaging compactness of the style. Not a single word he uses unnecessarily”. Parimēlaḻakar is, according to my opinion, very much indebted to Sanskrit sources, and sometimes he is entirely under the spell of ‘Sanskritization’ and ‘Brahminization’. I would not go as far as to say that he “twisted the text” “to fit his Brahmin prejudices”, but Brahmanic, Sanskrit sources certainly enriched and influenced his thinking, as well as his vocabulary and style. The one quality which is traditionally attributed to Parimēlaḻakar’s thinking and writing is teḷḷu, teḷivu, teṇmai, i.e. ‘clarity’. This quality gives him a great power of argumentation, one of the characteristic features of his commentaries.

There are, however, students of Tamil who prefer Nacciņārkkiņiyar (14th Cent.), who may probably be considered as the last of the great commentators; and I belong to them. He was accused of being “prone to looking for his own ideas in the verses”.18 This may be true, but it only shows his originality and boldness of thought. The same authors admit that “he does have a keen poetic sense and awareness of word values”. Nacciṉārkkiṉiyar is, above all, a very vivid and vehement author. He is also very learned, sometimes tending to display his great learning, and very sophisticated. I think, though, that he honestly tries to be impartial; that his commentaries show minute and critical observation; a clear mind and a vast erudition. His commentaries may always be classified as viruttis. According to V. V. S. Aiyar (op. cit. p. 41), “it may be said that good prose writing commences with” Nacciṉārkkiṉiyar.

18 C. and H. Jesudasan, op. cit. p. 216.

19 The term means “(white) pearls + (red) coral”; the pearls usually symbolize Sanskrit, the coral Tamil. According to a Malayalam grammar, Līlātilakam, maṇipravāḷa means bhāṣāsamskytayogam, i.e. “the union of the indigenous speech and Sanskrit”.

The so-called maṇipravāḷa19 style was accepted as legitimate by the Sanskrit-oriented Vīracōḻiyam (11th or 12th Cent. A.D.), a very interesting grammar writen by Puttiramittiraṉ, a Buddhist. Though maṇipravāḷam must be evaluated, in an overall estimation and assessment of the history of Tamil language and literature, rather negatively, it was a very picturesque, colourful and plastic style which had its own charm. Characteristic for this hybrid jargon is of course the exceedingly high percentage of Sanskrit loans, between 30-50% of the total vocabulary in a text (according to a count by J. J. Glazov, 1964, the percentage of Sanskrit loans in Tamil varies from 18 to 25%). Commentaries were written in this language mainly on Vaiṣṇava bhakti poems. To give an instance of this diction: in a piece of maṇipravāḷa prose containing approximately 125 words, I counted more than 35 Sanskrit loans including such tatsama (“appropriation” phase) loan-words like prahāsikka, atiprīti, kastūri, etc. Linguistically, there are three basic features of maṇipravāḷa style: 1) high number of Sanskrit loan-words; but this feature alone does not sufficiently characterize maṇipravāḷa; the loans must be, mostly, 2) unadepted to Tamil phonemic system, i.e. must be of the tatsama type; and 3) a great number of structural features of Sanskrit are translocated into Tamil (e.g. Sanskrit compounds are borrowed as such; there are many loan-translations; syntactic features of Sanskrit are found in Tamil constructions, etc.).

The commentatorial tradition has never been quite broken. When we speak about Nacciṉārkkiṉiyar as “the last great commentator” we should add “the last great medieval commentator”. The particular cultural and spiritual atmosphere in which the commentaries thrived and flourished, has never really ceased to exist, not even today, inspite of so many clashes between “tradition” and “modernity”. Above all, the initiatory structure of learning still persists, though in a much lesser degree than previously.20

20 I have had the honour and luck “to sit at the feet of a guru”, Mahavidvan M. V. Venugopala Pillai (born 1896), one of the great teachers of the indigenous Tamil scholastic tradition. He is an outstanding editor and glossator, and and excellent and kind teacher. In this connection, I recall the words of M. Eliade (Yoga: Immortality and Freedom, 2nd ed. 1959, 5):”Strictly speaking, … all traditional disciplines or crafts are, in India, taught by masters and are thus initiations; for millenniums they have been transmitted orally, ’from mouth to ear”. This fact is one of the most important components in the atmosphere which produced commentatorial literature.

In the “period of transition”, when the Tamil country passed gradually into Muslim and then English hands, and when Tamil as a literary language was sadly neglected, the tradition of the commentaries was still kept alive, and the greatest literary personality from the mutts, the monasteries, Civañāṉa Muṉivar († 1785), was a great commentator-probably a greater commentator and prose-writer than a poet. It is especially his monumental commentary on Civañāṉapōtam which contains his best prose-passages.

And so we come to those “makers of modern Tamil”, already mentioned, who were directly indebted, in their prose-writings, to the commentators of past ages. There were many of them, but probably the most important of those who “bridged” medieval and modern prose, was the controversial Āṟumuka Nāvalar (1822-1876). He was a very prolific writer, editor, translator, and commentator. Besides a great number of original prose-works (narrations of purāṇic stories in prose, polemic writings against Christian missionaries) and in addition to some translations (the Bible), he has written a number of commentaries, the chief of them a kāṇṭikai urai to the standard grammar Naṉṉūl, and a commentary to Kōyilpurāṇam. Although today we would probably describe his prose as dry, pedantic and monotonous, colourless and full of restraint, he deserves praise and gratitude for some of the great changes he introduced, and thus paved way for the writers of the “Tamil renaissance”. First of all, he “broke up” and “dissolved” some of the most rigid rules of sandhi; second, he “broke up” long complex sentences into brief, clear and simple sentences with finite verb forms (instead of using in abundance participles and absolutives). However, he was decisively against the use of colloquial, day-to-day forms and lexical items in written prose, and thus he was to a certain extent responsible for the affected, stilted, formal, stiff trends which are characteristic for a kind of Tamil prose even today.

But, in an over-all assessment of his work, one has to agree with the opinion of T. P. Meenakshisundaran who says: “Ārumukanavalar of the nineteenth century is the father of modern literary prose—the simple, elegant but grammatically correct prose”.21

21 C. and H. Jesudasan, op. cit. p. 176.

In the commentaries was thus incorporated a tremendous force of potentialities, a generator of syntactic and stylistic possibilities for a prose-fiction to arise and develop from within. And there is no doubt that modern Tamil prose is the result of a long development which has some of its deep roots in the commentaries.

The basic change leading to the origin of modern prose-fiction occurred in the conceptual sphere: so far, prose was primarily and almost exclusively reserved for eruditory and interpretative purposes (in short, for commentaries). In the 19th Century, under the impact of different forces (probably the most decisive among them Western influences), something else became the subjectmatter of prose-writing. The purpose and the function of prose changed drastically.

16.1 Appendix 1

Cilappatikāram XVIII, 11.51

“‘O, Sun of burning rays! Is my husband a thief?’

’He is not a thief, o woman with black fish-shaped eyes!

Glowing fire will devour this town!’ so said a voice”.

Aṭiyārkkunallār’s commentary on these lines:

“Therefore, o Sun with rays, you must know whether my husband is a thief. So she said, and he declared standing (there) in a bodiless state: Your husband is not a thief, o woman; look (how) this town which proclaimed him a thief, will be devoured by fire.

oḷḷeri = ‘the fire which will listen to your command’; ivvūr ‘this town’ ‘this town which said this’.

unṇumivvūr ‘will-eat this town’ = ivvūraiyuṇṇum ‘will-eat this town-accusative suffix’; a finite verb”.

16.2 Appendix 2

As an example of those medieval invocatory stanzas in praise of god (kaṭavuḷvāḻttu) which usually introduce Tamil poetic works I give a very close translation of Peruntēvaṉār’s introductory poem to Puṟanāṉūṟu. Peruntēvaṉār’s date was probably the 9th Cent.

In praise of God. Sung by Peruntēvaṉār who composed the Pāratam.

The perfect ascetic22

with abundant locks of falling hair

and with a jar which knows not want of water23

He—the protector of all creatures alive

The koṉṟai-flower24 which smells sweet after the rains

his chaplet

The koṉṟai-flower—a wreath of many flowers

on his chest

And the pure white bull25

he rides

The pure white bull

a banner of excellence

Poison26 beautifies his neck

Poison praised by the Veda-chanting Brahmans27

One side of him shaped into a woman28

He will hide and keep within himself

His forehead adorned with crescent moon29

That crescent moon

praised by all

by everyone30

22 Śiva

23 Gaṅgā; Śiva is Ganga-dhara, Bearer-of-the-Gaṅgā;

24 Indian laburnum, Cassia fistula; red I.1., C. marginata (DED 1808)

25 Nandi, the vehicle of Śiva (cf. Mahābhārata 13.6401). The bull also appears on Śiva’s banner as his emblem; Śiva is thus Vṛṣabha-dhvaja, “He whose banner is the bull”

26 Śiva is Nilakantha, “Blue-throated”

27 in Tamil, marainavil antaṇar (cf. DED, DEDS 126, 3897)

28 cf. Manusmṛti 1.32: “He divided his body into halves, one was male, the other female. The male in that female procreates the universe”. Hence he is called Ardhanariśvara, “The Hermaphrodite”

29 Śiva bears on his head as a diadem the crescent of the fifth-day moon

30 i.e. the gods (sura), the antigods (asura), the seers (muni), the heavenly musicians of Kubera (kinnara), the musicians of gods (kimpuruṣa), the half-vulture half-men (garuḍa) the guardians of earthly treasures (yakṣa), the demons (rākṣasa), the celestial musicians (gandharva), the perfect ones (siddha), heavenly panegyrists (cāraṇa), benevolent aerial spirits (vidyādhara), serpents (nāga), ghosts (bhūta), vampires (vetāla), hosts of stars (tārāgaṇa), aerial beings (ākāśavāsi), inhabitants of paradise (bhogabhūmi).

16.3 Appendix 3

As an instance of ciṟappuppāyiram, “The specific preface”, I give here an English rendering of the famous and very important preface to Tolkāppiyam by Paṉampāraṉār.

In the beautiful world

which speaks Tamil

between

Northern Vēṅkaṭam31 and Southern Kumari32

he explored

the sounds, the words, and the things,33

and he has fathomed

both the common speech and poetry,34

and inquired into the ancient books35

in the land stirred with Straight Tamil,36

and he designed a perfect plan

and gathered knowledge as in faultless words37—

he, the ascetic38

established in ample fame,

who revealed his name as Tolkāppiyaṉ39 versed

in aintiram40

surrounded by the surging waves;

and he has shown the system and the order

which starts with sounds

in a clear and unbewildering course;

and he dispelled the doubts

of the Teacher of Ataṅkōṭu,41

ripe in the wisdom of the four Vedas,42

whose tongue resounded with dharma,43

in the assembly of Pāṇṭiyaṉ,44

glorious and land-bestowing.

31 Ta. vaṭavēñkaṭam, i.e. probably the modern Tirupati north of Madras, a place which has been always considered the northern boundary of Tamiḻnāṭu

32 Ta. teṉkumari, prob. Kumarimuṉai, Cape Comorin; but may also refer to the river Kumari

33 Ta. eḻuttu, col, poruḷ, i.e. the three main subjects of the three books (atikāram) of the grammar

34 Ta. vaḻakku, the colloquial, spoken language; ceyyuḷ, the poetry, the language of poetry, the literary language

35 having inquired into (or having observed, having seen to) the ancient book or books; obviously an allusion to the predecessors of Tolkāppiyaṉ in grammatical tradition

36 lit. “in the land stirred (incited, animated) naturally by Straight Tamil”, i.e. centamiḻ “the correct, standard(?), literary(?) Tamil”

37 This is not quite clear; lit. “faultless word(s), speech, utterance”; according to some commentaries, “as in faultless speech, like in faultless utterances” (adverbially); according to Nacciṉārkkiṉiyar, it means “in the utterances (of the grammar, of the book itself) which are faultless”.

38 paṭimaiyōn = (Jain) ascetic

39 Nacciṉārkkiṉiyar uses this occasion to give his account of the legend about Tolkāppiyaṉ = Tiraṇatūmākkiṉi

40 aintiram = the aindra grammatical system; for some “Dravidian”-minded nationalists this sounds too “Aryan”, and so they read it as ain tiṟam, and interpret it as “five-fold skill” (i.e. eḻuttu, col, poruḷ, yāppu, aṇi); amusing but false.

41 Who this was, we do not know; the word ācāṉ is identical in meaning with āciriyaṉ “teacher, preceptor, guru” (epigraphic ācirikar, asiriyka), but also with arukaṉ < Argha-! It occurs frequently in Malayalam names (cf. e.g. the well-known poet from Kerala, Kumāran Ācān). The commentator says Atankōṭṭāciriyar, “The teacher of A.”; this is one of the data which point (vaguely) to a connection between the Tolkāppiyam and South Kerala.

42 nāṇmaṟai

43 aṟam

44 We do not know who this Pāṇṭiyaṉ king was. But it again seems to point to Southern Tamilnad or (today’s) South Kerala.