12 Śaiva Bhakti—Two Approaches

The literature of Tamil bhakti is an enormous complex of Śaivite and Vaiṣṇavite texts which must be regarded not only as an amazing literary and musical achievement and the embodiment of the religious experience of the entire Tamil nation, but also as a tremendous moving force in the lives of the peoples of Tamilnad. Unlike the pre-bhakti poetry which had to be resuscitated and revitalized and which became only recently the topic of attention and interest, Śaivite and Vaiṣṇavite hymns have played, since the very days they were composed until the present time, an immense, indispensable and often decisive role in the religious, cultural and social life of the entire Tamil people. To a great extent, the contemporary Tamil culture is still based on the bhakti movement, and it is only quite recently and among some strata of the present generation that the Tamils look at once farther back into the past of pre-bhakti days, and into the future, for inspiration and guidance.

It is probably impossible, at the present state of our knowledge, even to touch all aspects, forces, components and features of this vast literature, of this religious, philosophical and social movement. More than one large monograph would be needed to do so. In a series of essays the purpose of which is to introduce the reader to some of the most characteristic and crucial features of Tamil literature and culture, one has strictly to select an approach and to restrict the material rather drastically. If, therefore, the texts to be dealt with are restricted to the Śaiva texts there is absolutely no other reason for this than the present author’s relative ignorance of the works of Vaiṣṇava āḻvārs and the fact that some choice had to be made. Much of what can be said about Śaiva bhakti does apply to the Vaiṣṇava component of the movement; on the other hand, there are some very specific features pertaining to the literature of the āḻvārs; and hopefully it will be dealt with one day by a more competent expert.

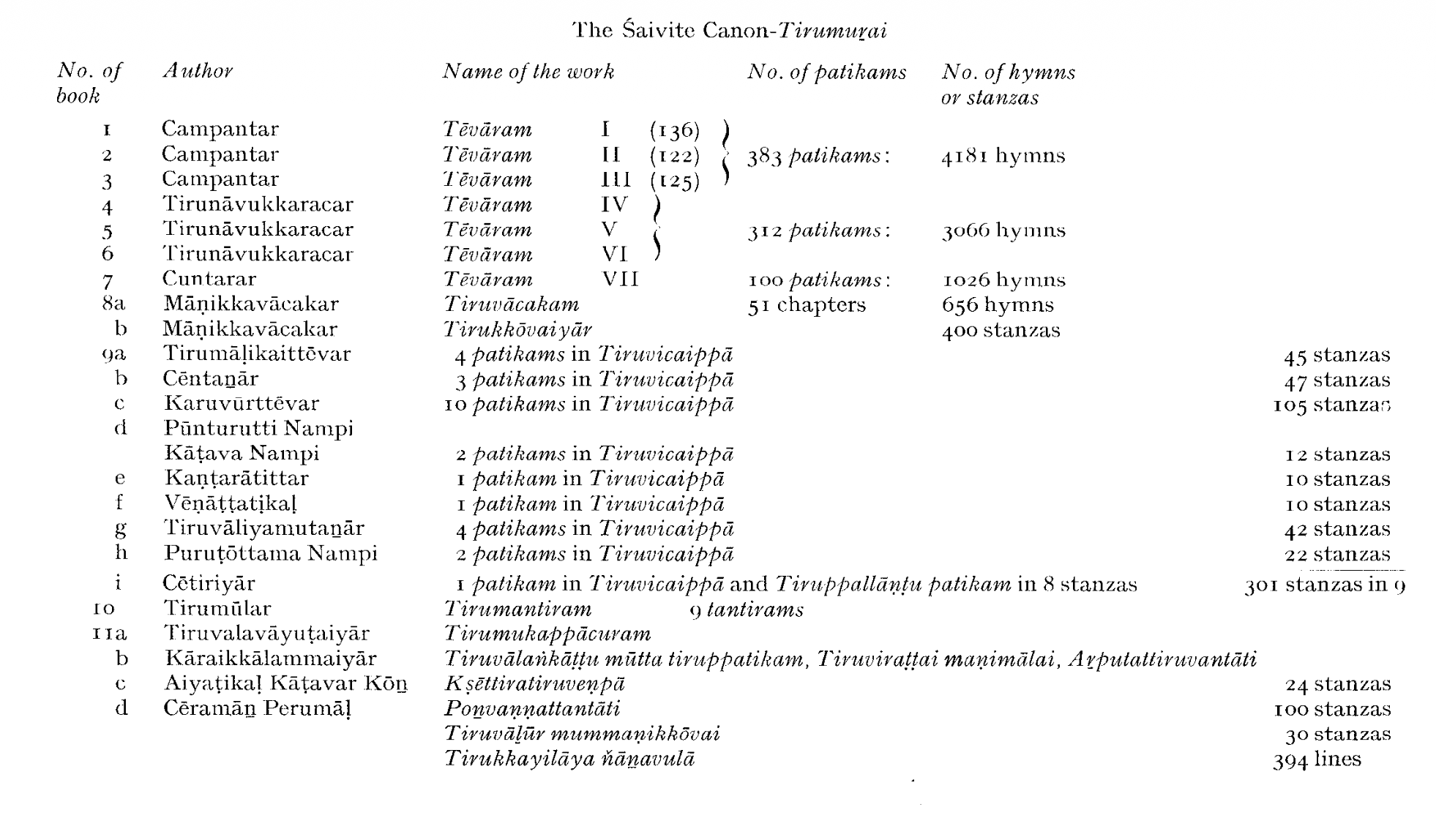

The immense dimensions of the Śaiva bhakti texts may be seen from Figure 12.1 which gives the names of the authors and their works as found in the twelve books of the Śaivite canon called Tirumuṟai. This body of literature includes a great variety of texts, beginning with the mystic hymns of the great trio, Campantar, Appar and Cuntarar, followed by Māṇikkavācakar’s Tiruvācakam and Tirukkōvaiyār, and ending with the “national epos of the Tamils”, the hagiographic Periyapurāṇam of Cēkkiḻār. Thus, the three characteristic features of this body of literature are its enormity, its heterogeneity, and the fact that it covers a period of at least 600 years of religious, philosophical and literary development (the earliest texts being probably the songs of Kāraikkāl Ammaiyār, round about 550 A.D., whereas the date of Cēkkilār is the 12th Century).

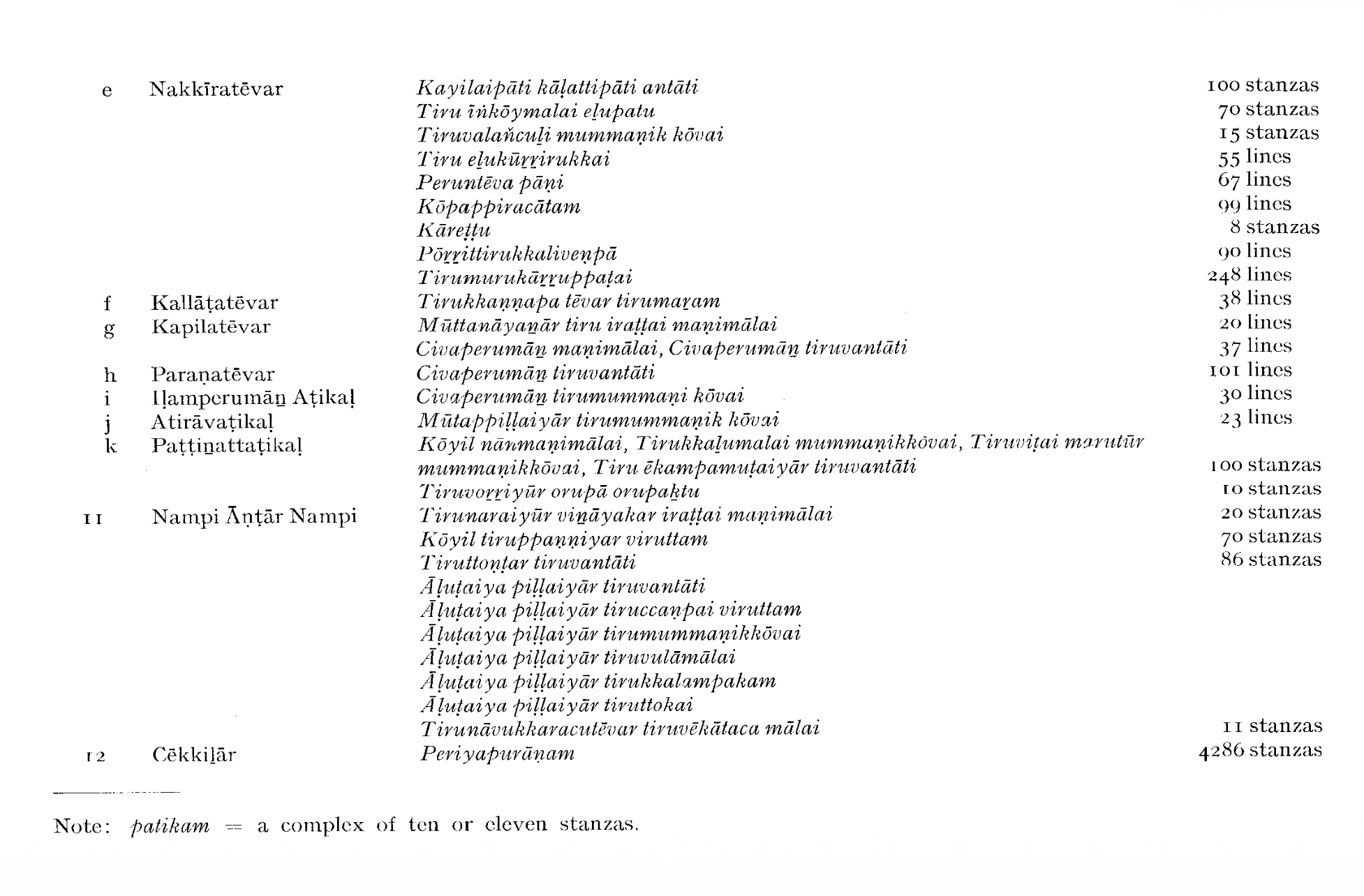

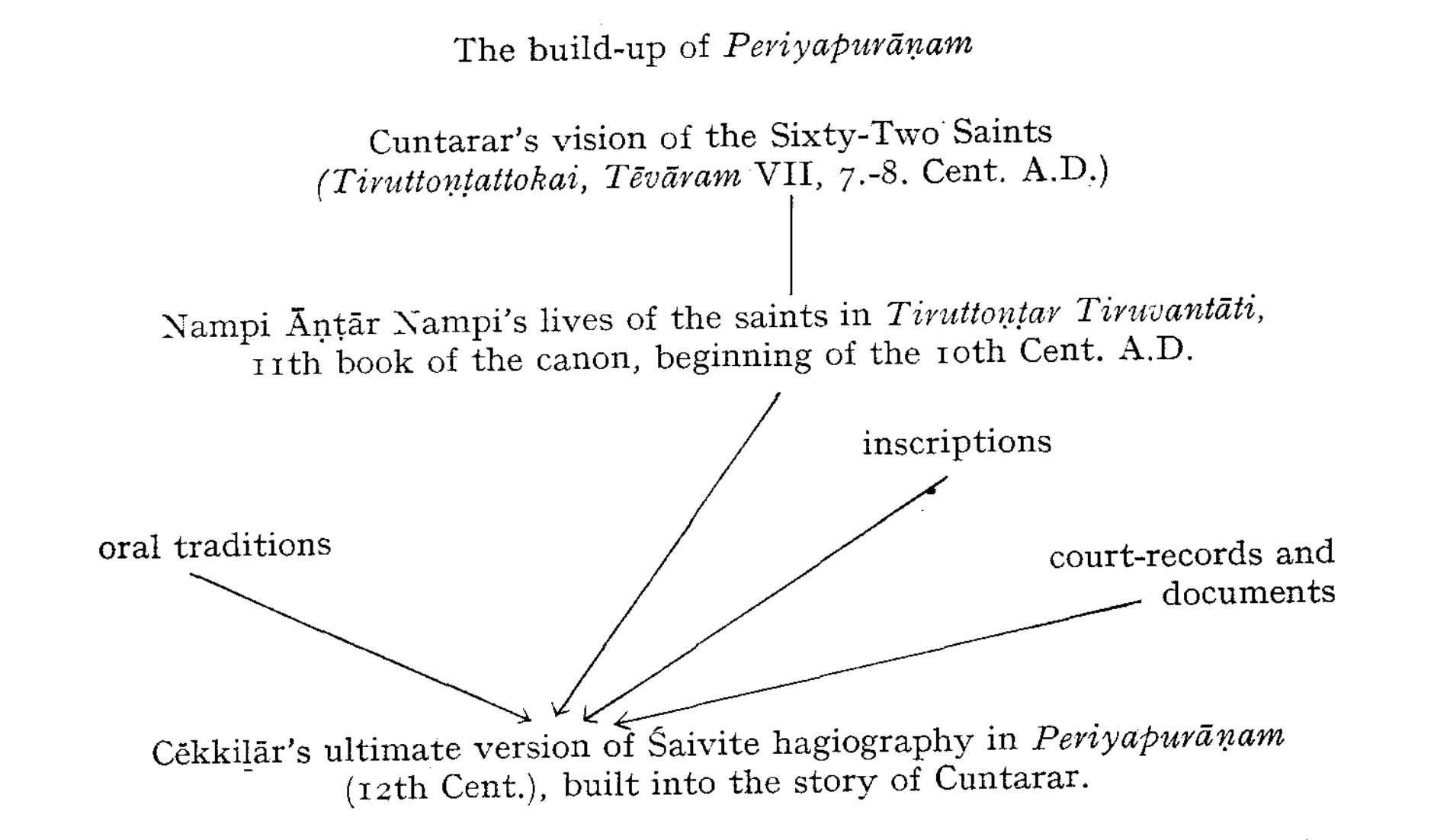

Nampi Āṇṭār Nampi (see 11 on Figure 12.1) is said to be responsible for collecting the Tēvāram hymns (the first 7 books of Tirumuṟai) and classifying them, some time at the beginning of the 10th Cent. A.D., into the seven books (on the basis of musical tunes).1 As the eight book, Māṇikkavācakar’s two great poems were added (they are not musical compositions). The 9th book of the canon consists of Tiruvicaippā or musical compositions sung in the Chola temples in the 10th and 11th Centuries;2 the term patikam (<Sanskrit) means “ten”; it is a form (consisting of 10 or 11 stanzas) which became popular in the bhakti period. The 10th book of the canon is of a very different nature: this is the Tirumantiram of Tirumūlar; his date is a matter of speculation; but since he is mentioned by Cuntarar (7621), he must be earlier than this poet. His work is tantric and yogic in nature, a superb philosophical poem, which becomes the point of departure for the highly interesting, eclectic school of the Siddhars. The 11th book contains works of very different age and character; the period covered by this book may stretch form the 6th to the 10th Centuries. Among the most interesting texts are those composed by Kāraikkāl Ammaiyār, probably the earliest of Tamil Śaiva saints and by Cēramāṉ Perumāḷ a contemporary of Cuntarar, the Tirumurukāṟṟuppaṭai (from Pattuppāṭṭu) by Nakkīratēvar, Paṭṭiṉattār’s stanzas, and the two poems on Saint Kaṇṇappar by Nakkīrar and by Kallāṭar (narrating the well-known story of Kaṇṇappar the hunter who became mad after God at the sight of a lingam, and who, when he saw the eyes of the lingam bleeding, plucked out his own eyes to replace them). Finally, the 12th book is the “Great purāṇam” by Cēkkilār: the crown of Śaivite literature, “the story of a perfect spiritual democracy” (T. P. Meenakshisundaran). The ultimate kernel of this tremendous epic, “national and democratic”, which had a universal appeal and an enormous influence in the Tamil country and outside, is Cuntarar’s vision of the sixty-two saints in his Tiruttoṇṭattokai, sung at Tiruvārūr in the presence of the aṭiyār, “devotees”. He has mentioned their names, sometimes with suggestive epithets, including those of his father and mother. By adding Cuntaramūrtti himself, we get the classic list of 63 Nāyaṉmār. Nampi Āṇṭār Nampi’s work is the next stage in elaborating the hagiographic tradition. Cēkkiḻār, as a minister of state, had probably access to inscriptions, documents, court-records, and in his epic he narrates the individual lives of the saints in separate purāṇas. Their stories are built around Cuntarar’s vision. Cuntarar’s story is in fact the unifying factor and the most general frame for the poem (or rather, chain of poems, since the structure of the epic is very loose). However, the basic unity of the whole epic is not that of form, but that of a message: however poor, insignificant and helpless a human being may be, nothing can prevent him from having an ideal; the meanest of the mean can rise to the highest spiritual level—in the life of service and love. What is important is the fact that, unlike the other epics of the same period, the sources of Periyapurāṇam are purely indigenous, purely Tamil; and that the poem is “national and democratic not only in its theme and its message but also in its language and its rhythm”.3

1 The date of Nampi Āṇṭār Nampi is fortunately rather ’well established. He speaks of the Chola king Ātittaṉ (Aditya) as having brought gold from Koṅkunāṭu and covered the temple hall at Chidambaram with that gold. He also mentions the death of this king. Ātittaṉ indeed conquered the koṅku country; and he ruled between 870-907 A.D. (cf. K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, A History of South India, III ed., 175).

2 T. P. Meenakshisundaran, HTL p. 131.

3 T. P. Meenakshisundaran, HTL p. 125.

The following fourfold approach toward the Tamil bhakti poetry seems to me to be the most fruitful:

the historical and sociological approach to bhakti as a literature of social and spiritual protest;

a synchronic segmental analysis of bhakti texts as religious literature;

a comparative approach to bhakti as mystical poetry, in comparison with other movements of Indian bhakti and mysticism; today, I think, most scholars would agree that bhakti was indeed “born on the banks of the Tamil land” wherefrom it spread to other India;4 in a broader perspective, Tamil bhakti may be profitably compared with other religions of grace (aruḷ), and/or with the mystical poetry of the East and the West (sūfism, Catholic baroque poets such as Juan de la Cruz, or Protestant mystics such as J. Böhme, etc.);

4 Cf. S. K. Iyengar, A History of Early Vaishnavism in South India, Madras University Series No. 4, Oxford Univ. Press, Madras, 1920, p. 10, who quotes a poem which says that bhakti* was born on the banks of the Tamil land, grew into womanhood in the Maharastra and in North India, and became old in Gujarat.

- a structural and structuralistic approach to bhakti texts conceived purely as poetry.

In this essay I shall try to give a brief and simplified outline of the first two approaches—the sociological and historical analysis of the movement, and the synchronic segmental analysis of the texts.

Between 600 A.D. and 900 A.D., Tamilnad was ruled by the Pallavas in the North, and the Pandyas in the South. There was a perpetual strife between the two. To the North of the Pallavas, the mighty Chalukyas of Badami were constant enemies of the Pallava kingdom. These three kingdoms were the first political units possessive of really large territories to have been formed in South India, and, as our data show, highly developed feudal relations prevailed in the social structure of these states.

Constant war or at least unceasing skirmishes among these three big powers, their efforts to enlarge their territories, the struggle against disloyal and disruptive tendencies, and the enormous growth of administration and bureaucracy—all this needed constant influx of money, and the burden of the expenditure had to be borne by the masses of the people.

This ever-growing feudal oppression of the masses aroused a protest, a mass-movement of popular dissatisfaction and opposition, which took the apparel of a religious drive. S. Vaiyapuri Pillai (HTLL, p. 100) speaks of a “bloodless revolution” which took place in Tamil India between the 7th-10th Centuries A.D.

Thus, according to one conception of social history of Tamilnad, the bhakti movement is to be regarded as the ideological reaction against early forms of feudalism and the first establishment and stabilization of class-society in South India; in the North of India, bhakti is regarded, by the same school of thought, as the expression of the struggle against a fully developed and centralized type of feudalism of the 14th-17th Centuries.

Among Tamil scholars, it was probably S. Vaiyapuri Pillai who first formulated a socio-political conception of the Tamil bhakti (HTLL, p. 100 ff; he speaks about “social equality of all” proclaimed by the religious revivalists, about bhakti becoming the “popular movement in the real sense of the word”, about “the language of the masses and their racy idiom” etc.). Needless to say the socioeconomic interpretation was worked out and refined chiefly by Soviet scholars (e.g. by Smirnova, Pyatigorsky) on the one hand, and by Marxist-oriented Tamil scholars and writers on the other hand (e.g. by Cāmi Citamparaṉār, C. Rakunātaṉ and others). In contrast, there are scholars, both Indian and Western, who regard the movement as a purely religious and ideological conflict, mostly as the reaction of a renascent Hinduism against Jainism and Buddhism.

Though I have a number of strong reservations about any vulgar socio-political interpretation of bhakti, it seems to me that its conception as a purely religious conflict is necessarily an oversimplification of the whole matter.

In what follows, the points made in favour of the socio-political interpretation of bhakti, and of the class-struggle-background-conception of the movement will be examined critically one by one.

First, there is the “class-origin” of the poet-saints. It was argued that most of the bhaktas or at least the most important of the earlier bhaktas belonged to the lower or depressed classes and castes of Tamilnad. The greatest number of the bhaktas were said to belong to the Śūdra veḷḷāḷar, and there were practically no Kṣatriyas among them; and, in the hagiographic legends, the Kṣatriyas are said to be usually portrayed in an unflattering light.

Most of these statements, made by some Indian and Soviet scholars, are, however, quite obviously incorrect. A rough investigation of the caste-origin of a number of bhakti poets shows these approximate numbers:

- about 35% of Brahmin origin (e.g. Campantar, Cuntarar, Māṇikkavācakar, Periyāḻvār);

- about 35% of Kṣatriya origin (e.g. Cēramāṉ Perumāḷ, Kulacēkara Āḻvār, Tirumaṅkai Āḻvār);

- about 20% of veḷḷāḷa (Śūdra) origin, e.g. Appar, Nammāḻvār;

- about 5% of low-caste origin, e.g. Tiruppāṇāḻvār;

- about 5% of unknown origin: Aṇṭāḷ was found as a baby in her step-father’s garden.

The argument is rather weak for yet another reason: high or low caste, it did not matter at all; the meaninglessness of caste in the eyes of the Lord is precisely one part of the message of the Nāyaṉmārs and Āḻvārs. In fact, if there is a class-conscious or caste-conscious standpoint discernible in these poems at all, it is (in contrast to the hero, warrior, aristocratic-oriented early bardic poetry) the Brahmins whose importance and excellence becomes progressively clearly underscored, whereas kings and princes appear in an unsympathetic light. And what more, there are some episodes which, quite au contraire to the “egalitarian” and “democratic” spirit discovered by some Marxist-oriented critics in the bhakti movement, show that even some of the most important authors of the movement were very much caste-conscious: according to Nampi Āṇṭār Nampi, an outcaste devotee (Tirunāḷaippōvār) destroys the disgrace of his low birth by entering the fire; according to Cēkkiḻār, God Śiva demands that the poor outcaste enters the fire and is purified before he is admitted to the sacred presence! The poems ignore the masses of peasants and common folk as such. Naturally so; something else was in the centre of their interest: the individual relation of a bhakta to God, and the inner tensions and outer conflicts resulting from this relation.

The second point, one with which we may agree to a great extent, is that Tamil bhakti literature is full of the spirit of social negativism.

A bhakta,5 as we saw, was usually a Brahmin, a Kṣatriya, or at least a veḷḷāḷa (landlord-community); he thus belonged either to the very top, or at least to the upper middle strata of the social hierarchy of medieval Tamilnad. The life of the devotee or toṇṭar was usually portrayed (in the canonical hagiographic literature) in the following way: After a rather stereotyped description of his birth and education, the great moment comes—the dramatic picture of the central episode: the conversion. This is inevitably preceded by a period of inner tension and by a sharp outer conflict. The important thing to note is that the nature of the conflict is usually social; and, invariably, in each episode the saint refuses to yield and becomes victorious (even if in death).6 E.g., when Vātavūrār alias Māṇikkavācakar gets into conflict with the Pandya king whose minister he was, and also with the entire Brahmin community; or when Cuntarar publicly opposes the decision of the caste panchayat. Śiva takes the side of the devotee who protests against society or tradition—frequently, though, in the very last moment, when his future devotee is in danger of annihilation, physical or moral.

5 The equivalent Tamil term is toṇṭaṉ, pl. toṇṭar, “servant” or aṭiyāṉ “slave”. There are two kinds of saints: the “hard” servants (vaṉtoṇṭar), the ones whom ordinary men cannot follow (they are the truly a-social or probably even anti-social ones), and the “soft” servants (meṉtoṇṭar) who became a model for all to follow. A typical vaṉtoṇṭar is, e.g., the hunter Kaṇṇappaṉ.

6 There is, in each episode, a dramatic plot, and an inner, psychological development of the hero: in this respect, the hagiographic stories are better than many modern Tamil short stories.

The victory against society and/or tradition, and the subsequent boon of poetic inspiration granted to the devotee by God as a gift of grace (aruḷ) frequently do not lead to full denial of society, to asceticism and renunciation; there are, of course, vaṉ toṇṭar who sacrifice their families, children, their life, without care and consideration whether their behaviour is just or unjust according to accepted social rules. But they can never be a model to be followed by others. Normally, the devotee goes on living within the society, but on a different, higher level; he is now independent of society, he is free of the society which is represented by two levels, the more general and higher level of the king and his court, and the more specific and lower level of the caste and the devotee’s family. The bhakta does not pay any attention to social matters; only two ties are now important for him: one between God and himself, another between himself and the other bhaktas.

Hence it is doubtful whether we are entitled to speak about the bhakti movement in terms of a positive social protest. Social negativism—yes; but an antisocial movement, or a revolutionary social protest—no.7 The utmost case of social negativism and perhaps the only one carried so far may be seen in the life story of Kāraikkāl Ammaiyār (about 550 A.D.). She breaks step by step all ties with her family, with her caste, with the society as a whole, and ultimately with humanity itself, and identifies herself with the uncanny demons, ghosts, “devils” (pēy) who witness Śiva’s wild dancing in Tiruvālaṅkāṭu.

7 Even this is doubtful in case of some poet-saints; thus e.g. Cuntarar, as T. P. Meenakshisundaran says in op. cit. 74, “was a great political force in his times and sang the praise of the Pallavas”, cf. Tēvāram 8240. His life seems to have been “a divine family life, a divine social and perhaps political life”.

8 Periyāḻvār speaks about the devotees as toṇṭakkulam, “the clan of servants”. For the “servant’s servant”, cf. one of the titles of the Roman pontiff: servus servorum Dei.

The third point made for the socio-political interpretation of bhakti is that the texts disregard, transcend and deny all social privileges and all caste prejudices. This feature was called “democratism” or “egalitarianism”. T. P. Meenakshisundaran speaks about “perfect spiritual democracy” and “a spiritual democracy of love and service”. We may agree with the term as long as it is accompanied by the qualifier “spiritual”. Of social or political democracy, however, there are perhaps no traces in the texts. The equality and freedom refer to the bhaktas, to the devotees, and to them only. Just as there is no real social protest on behalf of the exploited masses of the common people but only individual social conflict of the devotees, there is no fight for freedom and equality on behalf of the oppressed. Only the devotees of Siva are equal. Only they are filled with the feeling of wonderful freedom. They have one master alone—Śiva; they are “slaves” (aṭiyār), “servants” (toṇṭar) but also comrades and companions (tōḻar) of Śiva. In an admirable hymn typical of this feeling of freedom, Appar sings: nāmārkkum kuṭi yalōm namaṉai yañcōm “We are subjects to no one; we do not fear death… It’s joy for us through life, not pain!” Towards each other, they, too, are “slaves” and “servants”: aṭiyārkkum aṭiyēṉ, “I am the servants’ servant”, says Cuntarar. And a similar situation prevails among the Vaiṣṇavites.8

Before a man or woman becomes a devotee of Śiva, he or she has to give up all privileges, based on high social status or wealth. Thus Māṇikkavācakar renounces completely all his worldly ambitions and his wealth, and again and again stresses the necessity of doing so; Cuntarar becomes, immediately before his marriage, the servant (toṇṭar) of God, and after he gives up the privilege of belonging to the highest caste, he becomes the Lord’s comrade (tōlaṉ). However, as already stressed, the spirit of freedom, equality and service pervades only the “brotherhood”, the “clan” of the devotees.

Bhakti is a personal and emotional approach to God; the individual character of such contact with the Divine means that it occurs outside of any corporation which has a specialized and privileged knowledge of sacred texts and ritual.

In Buddhism and Jainism, the liberation of the individual from the fetters of “human bondage” was achieved by total denial and renunciation. In bhakti, it is achieved by total devotion and worship. The liberation of the individual from the grip of social oppression was achieved, in Buddhism and Jainism, by his getting rid of society itself; society as such became an enemy of the individual. And these two religions—at least in their later “degenerate” forms in the South—were indeed strongly antisocial. In spite of the rivalry between each other, they were strong enough to be very probably a powerful antisocial factor in the Tamil society in the middle of the first millennium A.D. That is one of the reasons why, in the second half of the 1st millennium, the society and in particular its rulers turned away from Jainism and Buddhism.

The excesses committed in the name of these religions provoked many individuals and whole social strata to resistance. The early poet-devotees speak about Buddhism and Jainism with genuine hatred, stressing the antisocial behaviour of the Buddhists and Jains.

The opposition towards Jainism is well seen in Appar’s own life story: He had been a Jain himself; he led a life of vain mortification of the body, denying it even the simplest pleasure of a bath, moving around as a naked ascetic. This kind of religion built on a series of negations brought him only an unbearable inner tension (which manifested itself, incidentally, by a chronic stomach-ache). He became a convert to Śaivism, and found the omnipresent, omnipotent Lord, whom he could love and who would never fail him. Or consider Cuntarar’s contempt of the Jains: he sneers at their names, their unclean and antihygienic habits, their ways of eating and living, and even at their shaven heads. According to persistent tradition, Cuntarar was responsible for the annihilation of 8000 Jains in Maturai.9 He went as far as to deny, very unjustly, the Jains their great merit of cultivating Tamil learning. Cuntarar, too, speaks of the Jains and Buddhists with contempt and ridicule: thus, in his hymn 33.9, he mentions the “shameless Jains, jeering at everyone, who recite the (meaningless) sounds ñamaṇa ñānaṇa ñāṇa ñōṇam.” Toṇṭaraṭiyāḻvār, a Vaiṣṇava saint, condemns, too, the Buddhists and Jains and speaks of them as of “untouchables”.10 Even the great Periyāḻvār of whom it was said that “his poems show no hatred of other religions” (M. S. Purnalingam Pillai), cries out: “Snatch the rice from the mouths of these who burden the earth! Stuff them with grass instead!”

9 Nampi Āṇṭār Nampi, Āḷuṭaiya Piḷḷaiyār Tiruvulāmālai, 59 and 74.

10 Tirumālai, 7.

We must of course allow for some amount of exaggeration but it is obvious that, by the middle of the first millennium A.D., Buddhism and Jainism must have lost practically all of their attraction, and the poet-saints became allies of the kings and the princes who, as already said, turned away from Jainism and Buddhism (many of the bhaktas, both Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava, belonged themselves to the ruling classes, e.g. Kulacēkarāḻvār, the king of Kolli, Koṅku, Kūṭal and Kōḻi; or Cēramāṉ Perumāḷ; or Tirumaṅkai Āḻvār, the prince of Maṅkai in Tiruvaḻināṭu, etc.).

Politically, Jainism and Buddhism were, in the middle of the first millennium, connected with foreign, non-Tamil powers, chiefly the Cālūkyas; and this probably induced the Pallava and Pandya kings to reject Jainism and to adopt Śaivism.

Another very powerful factor was language. Though the Jains cultivated arduously literary Tamil since the earliest times, the style of Tamil they fostered became, to a great extent, artificial and very much removed from the idiom of the masses. On the other hand, Buddhism and Jainism were to some extent even linguistically alien. In contrast, the language of the masses reached the innermost texture of the literary idiom of the poet-saints; the masses understood well the new language of bhakti poetry; it sounded to them “at once direct, clear and forceful” (S. Vaiyapuri Pillai). The Sanskritic diction of the ever more influential Brahmins added to the richness of the diction of bhakti poetry; and the melodies of the religious songs were obviously based on popular songs, on folk-tunes.

The anti-Buddhist and anti-Jain bhakti movement coincides in Tamilnad in time and content with the establishment and spread of a strong Tamil national feeling and with the political expression of this fact—the origin and spread of the powerful Tamil kingdom of the Pallavas under Mahendravarman I (580-630 A.D.) and his son Narasimhavarman I (630-668 A.D.). In the second half of the first millennium, Buddhism and Jainism are regarded as something alien, something which is inimical to this national self-identification of the Tamils.

However, the reaction against Buddhism and Jainism had yet deeper roots. The purely intellectual ethical conceptions of the Jains were not and could not be popular among the masses; the Jaina cult was also somewhat too abstract and unattractive; and the excesses of Jaina asceticism were ridiculed by the folk as well as by some intellectuals. Art, literature and music were basically regarded as dangerous by Jains and Buddhists, and their attitude became later openly negative. The whole world was full of temptation and misery; even womanhood, motherhood and childhood lost their charms.

In contrast to this, early Śaivite saints glorified womanhood and motherhood (cf. Campantar, Tēvāram 1425). Nature became a form of śakti; indeed, God has no other form (Appar, Tēvāram 4552, 4560). The whole material world seems to dance and sing and play (viḷaiyāṭu); this is a dance of worship of the Lord (Tēvāram 2703). Art and music became divine in temple worship.

The endless personal loyalty of a bhakta to a personal and very real God11, and love, not suffering and renunciation, are the central motives and features of bhakti: including sexual love and eroticism, which is not a hindrance, but, on the contrary, frequently a precondition to divine love or, at least, its standard symbol. There is in fact a direct connection between the idealized and typified love of the akam genre in the early classical poetry, and the ecstasies of the eternal love between the soul and the Lord. The trend may be followed from the akam pieces through Tiruvaḷḷuvar’s Kāmattuppāl and Tirumūlar’s basic utterances like anpē civam “God is love” to the relation between the human and the Divine as expressed in the great Śaivite and Vaiṣṇavite poet-saints.12

11 This may incidentally be one of the reasons why the Pallava and Pāṇṭiya monarchs were converted to Śaivism. The endless loyalty to a personal God was used as a kind of model and projection for an unconditional loyalty of the subject to the king.

12 It is usually the bhakta who turns into woman craving for the embrace of the Lord; i.e. the human soul is female, God male. Exceptionally, as in Māṇikkavāsakar’s Tirukkōvayār, the soul is the male and the Lord the lady-love. Frequently, the bhakta is a slave, a servant of the God-king; sometimes, he is a child, and God his mother; he is the lotus-flower and God the sun; he is Yacōtai and God her child Kṛṣṇa; a woman devotee is the woman longing passionately for Kṛṣṇa’s embrace; or, as in the case of Kāraikkāl Ammai, she is a mad demon (pēy), and the Lord is the dancing Siva.

The relation to the object of the cult develops individually, but within the community; asceticism is not obligatory; frequently it is missing altogether (cf. the life-story of Cuntarar who married first a temple-girl at Tiruvārūr, Paravai, then a vēḷāḷa girl, Caṅkili, at Tiruvoṟṟiyūr, and these two women occupied a large portion of the life of this “licensed friend” of God). The bhakta brings, to his God, his economic and social position as sacrifice-but this sacrifice does not mean a denial of the society as a whole, only the acquisition of freedom from social ties. The devotee of the Lord remained living within the community and the society, in full enjoyment of all advantages provided by social life, but, at the same time, living on a higher level, ignoring any ties and restrictions which society imposed.

Finally, the cult of sacred places, a feature so typical for both Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava bhakti in the South, which was probably the most “popular” element of the movement, added much to its spread and attraction. The theology of bhakti was realistic to the extent that it did not accept the conception of the phenomenal world as an illusion; it was theistic: God was individualized and made completely real, so to say “solidified” in a very concrete form of the idol worshipped in the temple; at a given moment in time, God was dwelling in a concrete and near place, in a familiar local shrine. And what kind of God! Śiva took on a colourful, vital personality, absorbing much of the local couleur, and the attention of the people; and perhaps even more absorbing became the personality of Viṣṇu—in the role of child, lover, and intimate companion of the devotees. So, in comparison with the decayed, deteriorated Southern Buddhism and Jainism we see in the Tamil Hindu revival the triumph of emotion over intellect, of the concrete over the abstract, of the acceptance of life over its ascetic denial, of something near and homely against something alien and distant, and, above all, the acceptance of positive love against cold morality or intellectually coloured compassion.

It was said at the beginning of this chapter, that there was another productive approach to Tamil bhakti literature—the structural analysis of the texts into segments.13 A few preliminary remarks are necessary.

13 Elaborated in detail by A. M. Pyatigorsky in his book Materialy po istorii indijskoj filosofii (Moscow, 1962), pp. 76-146.

The religiosity of a text includes basically two elements. The first element is that of the function of the cult: the composition, the uttering or chanting of the text, or the acceptance of a given text or its portion is directed to call forth or to sustain the connection with the object of the cult. The second element is that of the information pertinent to the relation of the subject of the cult to its object.

This information is classified into the following segments:

- S1 - the interior state of the subject of the cult;

- S2 - the external actions of the subject of the cult;

- O1 - the respective reaction of the object of the cult in relation to the subject;

- O2 - the state, qualities or actions of the object of the cult irrespective of the given relation to the subject; O2 has usually the form of a synchronic projection of an event in diachrony.

As an example of a stanza which illustrates the complete pattern S1 S2 O1 O2 we may quote one of the earliest Śaiva bhakti poems, ascribed to Kāraikkāl Ammaiyār:

O heart! Praise always in the fullness of love

Him the Bestower of good, the Pure one with falling locks,

Him who likes to give shelter to hissing snakes in his hair,

Him who will redeem us when the day comes.

- S1 = “O heart …. in the fullness of love”;

- S2 = “praise always”;

- O1 = “who will redeem us when the day comes”;

- O2 = the rest.

Indian religious literature may be divided into three kinds of texts: specific religious texts (hymns), narrative religious texts, and religious-philosophical texts. One and the same text may acquire or loose its specific religious function depending on its setting in the space and time coordinates. Reflective-religious, or religious-philosophical literature is that kind of literature in which O2 plays the central part but is removed from its cult-relations and appears in an abstract and categorized shape. In ancient Indo-Aryan literature the first kind of texts is represented by Vedic hymns, the second by the purāṇas, and the third by the upaniṣads, the śāstras and the āgamas.

The function of the text and its content, i.e. the information it gives, are independent of each other. We find e.g. a number of texts in India which give no information related to cult and religion, and yet they have become indispensable for the cult as the texts of the cult, depending upon their diachronic situation.

The segmentation of the information into S1, S2, O1 and O2 enables us to perform a series of internal and external comparisons. When, for instance, we compare the hymns of the Tamil Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava saint-poets of the 7th-10th Cent. A.D. with the Vedic hymns, we may observe a set of common features but also features which are sharply contrastive: one of the most important distinctions is the hypertrophy of S1 in many Tamil hymns, and its almost complete absence in Vedic hymns.

The intimate side of worship is highly developed in the Tamil hymns (contrary to Vedic texts). The most important feature of the Tamil hymns is the relation S2 O1: what does the devotee ask for when addressing God, and what does God grant him.

The analysis of S2 O1 shows that in the Vedic hymns man demands from God material goods for himself, and denial of these goods to his enemies. Such demand is usually accompanied by a ritual in which one brings to the gods in small quantities the same which one wants from them in large amounts.

In the Tamil hymns, the devotee asks God to grant him knowledge of himself and knowledge of God, so that he can see him, love him and become one with him.

Both in Vedic and Tamil hymns we frequently encounter the phenomenon of substitution; the object of the cult is no more God himself but some of his attributes. Sometimes the substitution phenomenon is very simple (e.g. the simple pars pro toto relation); but it may also become more complicated: the devotee addresses a third object, a kind of “duplicate” of the original subject of the cult, which has some unique, specific relation to the sphere of S2 O1 and serves as the ideal mediator between the subject and the object of the cult. In Vedic hymns, such substitute is usually an element of the material rite, e.g. ghĩ; in the Tamil hymns, it may be the heart, the mind, the soul of the bhakta.

The relation of the subject of the cult to its object has predominantly material character in Vedic hymns, and it lies outside the cult; au contraire, in the Tamil medieval hymns, the relation of the subject to the object of the cult remains fully within the sphere of the cult, and has predominantly spiritual and/or emotional character. Vedic hymns are, as to their function, a part of the cult, the part which reflects and assists the material ritual; the Tamil hymns are the centre and the basis of the cult, in relation to which the material ritual is only a facultative component of S2.

There is yet another important difference: the object of the Vedic cult was conceived as existing in nature in general, and, at the same time, at any given place; in other words, the object of the cult was delimited only on the cosmic plane. In the Tamil hymns, however, God—Siva or Viṣṇu—is considered to dwell, at a given moment in time, exclusively at a given place, in one of the great shrines of the South. This “here and now” atrribute of God is part of the phenomenon which has been called henolocotheism.

The segment O2 fills the greater part of Sanskrit purāṇas: the personal story of the object of the cult. The object of the cult received, much later, his “second life” in the South of India. The important changes concerning this “second life” were connected with the cult as such and with its practical part, not with the conception of the object itself beyond the sphere of cult-relations.

In the Tamil hymns, the material of O2 is usually telescoped into the epithets. There are two kinds of epithets in these hymns. One group entered Tamil literature from (or through) Sanskritic literature and has no relation to Tamil ritual practice: e.g. when Kṛṣṇa, as Viṣṇu’s avatār, is described as “the one who had devoured the entire universe”; this is an allusion based on the Bhāgavatapurāṇa; it had lost so to say the temporal coordinates of the puranic episode and was telescoped into the Tamil hymns as a “flattened” synchronic epithet.

Another kind of epithets has the henolocotheistic character; that is, it is connected with the particular place of abode of the deity; or with the intimate sphere of the devotee’s religious experience. This group of epithets has nothing in common with the Sanskritic tradition, it is completely indigenous.

The fact that S1, S2, O1, O2 were posited as segments of the information given in the hymns enables us to compare, from one convenient point of view, the saint-poets with one another. Here I shall give a very brief comparison of the hymns of the four great Śaiva nāyaṉmār, Appar, Campantar, Cuntarar and Māṇikkavācakar.

Campantar’s poems contain all the elements of information which are typical for the whole complex of Śaiva bhakti texts. However, there is in his songs a definite predominance of the segment O2. The content of S2 is mostly Campantar’s struggle with the Jainas. On the other hand, the intimate, lyrical part of religious experience is relatively weakly developed in his work. He is less emotional than the other bhaktas; the greater part of his work is filled with material related to O2, mostly in epithetic form. A favourite substitute for God is, in his poems, tirunīru, “the sacred ash”; and also patam, “the foot”; aṭi, “the footstep” of the Lord. One of the diagnostic features of his poetry is also his preoccupation with Śiva’s abodes.

In his ears, he has the palm-leaf roll;

riding a steer, crowned with the pure white crescent-moon,

besmeared with ashes of the jungle burning ground,

he is the thief who stole away my soul.

He wears a flower-garland, he, who in former days

when praised and worshipped, showered grace

and came to famous Brahmāpuram.

He is our mighty Lord!

In contrast to Campantar, the poems by Appar are almost exclusively emotional. There is rich material connected with the individual acts of worship and with the autobiography of the poet. Therefore, apart from O2 which is also strongly developed in Appar’s poetry, there is a strong element of S1 and S2. One of the important features of Appar’s poetry is his antiritualism; this fact of the worship being fully transferred into the spheres of emotion and vision seems to anticipate the most typical features of the poetry of the Cittar and of Tāyumāṉavar.

One of his best-known poems begins with the line nāmārkum kuṭiyallōm namaṉai yañcōm.14

14 Appar, Tēvāram, Kaḻakam ed., 357.

To none are we subject!

Death we do not fear!

We do not grieve in hell.

We never tremble

and we know no illness.

We do not crouch and crawl.

It’s joy for us through life,

not pain!

In Cuntarar’s poetry, there is again a strong preference for S1, but of a different kind than by Appar. Cuntarar’s poetry is very near to erotic lyrics, the material of his hymns is most intimately connected with his innermost emotions, with the events of his life, and even the epithets, forming the segment O2, are connected with the intimate aspect of worship, with the body of the Beloved.15

15 There is a popular saying in Tamil, attributed to Śiva himself: “My Appan sung of myself, Campantaṉ sung of himself, Cuntaraṉ sung of women”.

I was sold

and bought by you.

I am no loan.

I am your slave

of my own free will!

You made me blind.

Why, Lord,

did you take away

my sight?

You are to blame!

If you will not restore

the sight of my other eye—

well, may you then live long!16

16 Cuntarar, Tēvāram, Pat. 95, 2.

Finally, there is Māṇikkavācakar, whose work is usually considered to be the most typical and the ripest expression of Śaiva bhakti in Tamil literature.

The structure of his Tiruvācakam is rather complex. It has 51 chapters, containing 656 hymns. After the akaval portion, which contains an entire inventory of Śiva’s epithets, and the whole canon of accepted forms of Śaiva worship, follow the patikams, divided usually into quatrains with refrains or catch-words. There is a clear hypertrophy of the segment S1. Religious emotion achieves, in these poems, a strenght and fullness hardly achieved anywhere else. The love of the devotee, which is the central and basic feature of his religio, is responded to by the object of worship with aruḷ, divine grace. The segment S2 is almost entirely suppressed, since everything what happens on the side of the subject of worship happens within his heart and soul. Most of his hymns have the pattern S1 O1 (O2). The central and most important portion of his hymns concerns the relation S1O1.

O kuyil who calls from flower-filled groves

listen

He came as a Brahman and revealed

his lovely rosy feet

He is mine

he said with infinite grace

and made me all his own

The Lord Supreme

Go

All glowing flames his form

Call him once again

—

Tiruvācakam, Kuyiṟpattu 10

(Transl. by S. Kokilam)

Below an analysis is given of two quatrains from his Tiruvācakam (in A. K. Ramanujan’s translation).

I am the very last, but in your mercy you made me your own,

O Lord of the Bull. But, look, now you give me up,

O Lord, dressed in the fierce tiger’s skin, O King everlasting of

Uttarakōcamaṅkai,

O Lord of the matted locks. I faint. Support me, Lord, Our Own.

I refused your grace in my ignorance, O jewel!

You loath me. Look, you give me up. Cut down

this chain of acts and make me yours, O King of Uttarakōcamaṅkai!

Don’t the great ones always bear with the lies of tiny puppies ?

Observe the fact that, in both poems, the segment S2—in contrast to Campantar’s and Cuntarar’s hymns—equals zero; the segment O2 is developed, but not too strongly (in contrast, e.g., to Appar’s or Campantar’s poems). It is the segments S1 and O1 which are filled with material. The second hymn in particular has a neat pattern of S1 O1 (O2).

| S1 | S2 | O1 | O2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Is the very last of Śiva’s devotees | Made him his own through his mercy | Rides the bull / Is clad in tiger-skin | |

| Fears to be forsaken by Śiva | Gives him up | King of Uttarak. | ||

| Is tired and faints. / Prays to be supported by Śiva | (Supports him) | Has matted locks / The Lord | ||

| 2 | Lives in ignorance | Loathes the devotee / Gives him up | Jewel | |

| Refuses the grace | Destroys the devotee’s chain of actions | |||

| Fears to be forsaken by Śiva | Makes him his own | King of Uttarak. | ||

| Considers himself to be a miserable dog | Bears with the devotee’s lies | He who is great |

Another typical feature of Tiruvācakam is the development of the system of the object—an elaboration and “universalization” of the object which results in the fact that the object engulfs as it were the whole phenomenal world including the subject of the cult. Thus, the hymn is, in part at least, transformed into a religious-philosophical treatise, and worship is accompanied by reflection:

He is the Ancient One, who creates the Creator of all;

He is the God, who preserves the Preserver of things created;

He is the God who destroys the Destroyer;

But, thinking without thought, regards the things destroyed.

—

(Transl. G. U. Pope, Tiruvācakam III, 13-16)

The culmination of this development is reached in the Civapurāṇam . According to this poem, the only aim of the poet’s life, of his trials and efforts, is the complete liquidation of karma. To achieve this, one must be born as a human being, after passing through different births not only in the organic but also in the anorganic nature.

This cur

in ugly existence

to praise you

knows no words

As grass as weed

as worm as tree

as carnal beings

as bird and as snake

as rock as man

as devil and as demon

as ascetic

as god

as being and non-being

all creations

I’ve lived and tired

My Lord

My cosmic eye has seen

your golden feet Today

I’ve reached my home

—

Tiruvācakam, Civapurāṇam 24-32

(Transl. by S. Kokilam)

Śiva gives the soul the privilege to be born in human form. Śiva grants the devotee the gift of love and true knowledge; and, finally, Śiva helps to annihilate completely the devotee’s karma. Thus karma has lost its absolute character; it is no more the transcendental and eternal law. It is Śiva, the God, at once transcendental and personal, who is absolute in every sense of the term.

Civapurāṇam has been called “The Tamil Upanisad”. Not only the Civapurāṇam, but the whole of Tiruvācakam is the culmination of Śaiva bhakti hymnic literature, and, at the same time, the beginning of the specific system of Śaiva Siddhānta philosophy. It has always played an enormously influential role in the entire spiritual culture of Tamilnad.