20 The “New Poetry”

The term New Poetry is used here in a limited and technical sense of the Tamil expression putuk kavitai or putiyak kavitai, i.e. for the works of a particular group of “new poets” who made their appearance approximately after 1958-59, and whose poems were collectively published for the first time in October 1962 in a slender yet path-breaking volume entitled Putukkuralkaḷ “New Voices”. It is therefore not used for post-Bharati Tamil poetry, not even for post-Bharatidasan Tamil poetry. I do not deal in this chapter with such influential modern poets as S. D. S. Yogi, not even with some “young” contemporary poets like the “people’s bard” Paṭṭukkōṭṭai Kalyāṇacuntaram, or like the very popular Kaṇṇatācaṉ. All these are modern poets, but not “new” poets in the sense of the term mentioned above. These modern poets may indulge in vers libre, or be fiercefully politically oriented and proclaim themselves as ultra-red revolutionaries, but, in fact, there is nothing basically new, creative, and “revolutionary” about their writing. Their poetry is a sort of anaemic imitation of either Bharati or Bharatidasan or S. D. S. Yogi.

What is meant by the term “new poetry” here is different both from the moribund orthodox pandit-like versification as well as from the sentimentally romantic outpourings of the hosts of “modern” but not “new” poets.

The “new poets” have, in fact, general features in common which distinguish their work from the rest.

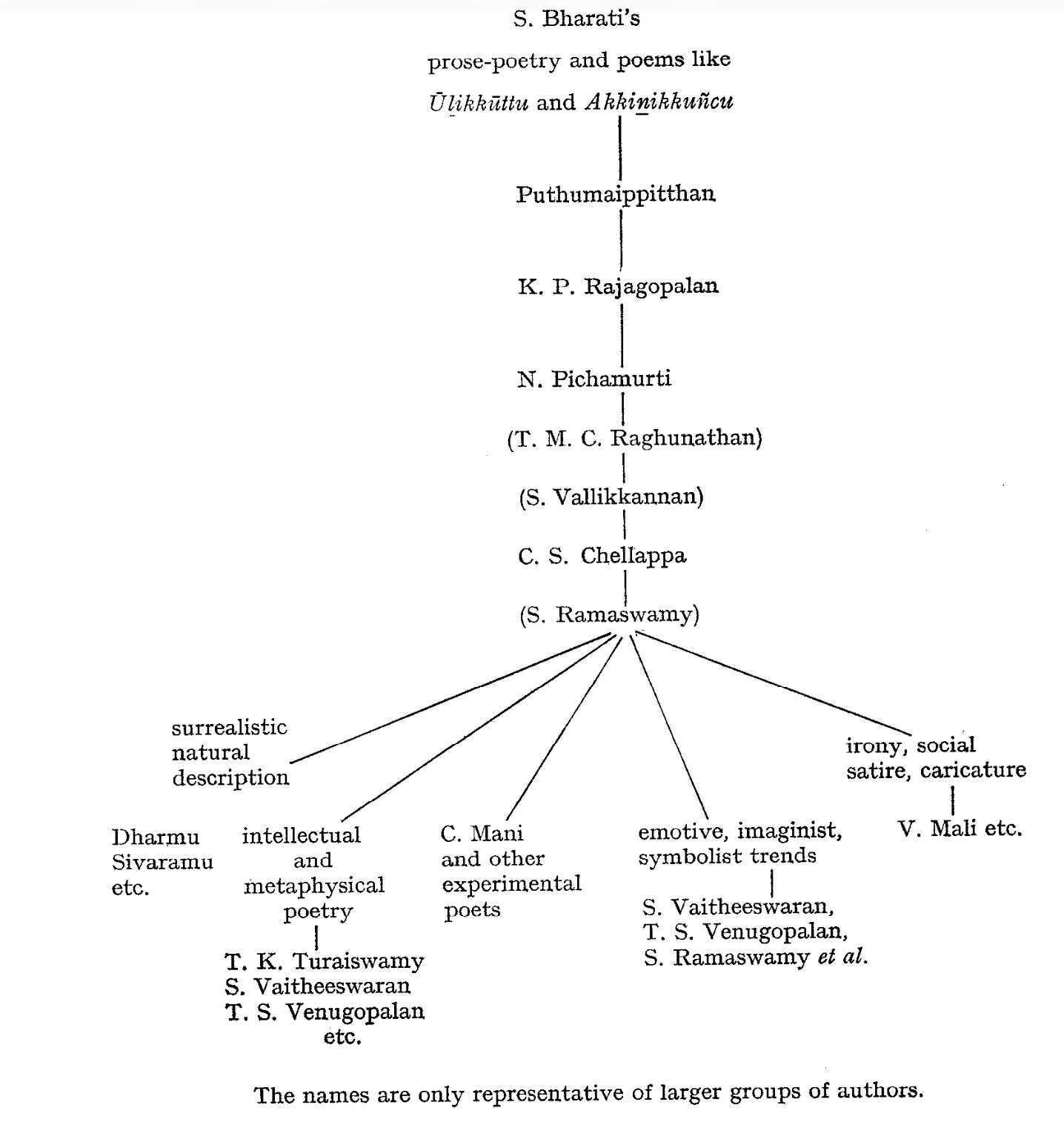

Historically speaking, the “new poets” have a very definite line of descent which is indicated in the chart appended to this chapter (Figure 20.1) and which includes, in succession, the four great names of S. Bharati, Puthumaippitthan, K. P. Rajagopalan and N. Pichamurti. The other features of “new poetry” are:

Radical break with the past and its traditions, though not a negation of the cultural heritage.

Disregard for traditional forms and prosodic structures, and a new utilization of basic prosodic properties of Tamil.

A great amount of experimentation with language and form of poetry, based on intellection, and at least some acquaintance with French, English, American etc. modern poetry.

Preoccupation with very contemporary matters and inclusion hitherto ignored sujets. If traditional subjects are handled, they are treated from a new, non-traditional angle and point of view.

The beginnings of “new poetry”—if we disregard a somewhat similar intellectual and emotional milieu of some of the Siddhar poems—may be found in Subrahmanya Bharati’s (1882-1921) works, in his “prose-poetry” as well as in a few stray poems which are very striking from the point of view of form and content. Incidentally, Bharati considered himself to be a spiritual descendent of the cittar:

“Siddhars many have been ere my time!

I am another come to this land”.

Bharati’s prose-poems and free-verse experiments opened new vistas and tried new techniques in Tamil poetry as early as during the decade of 1910-1920. Consider e.g. lines like these:

Mind is the enemy within

And cuts our roots.

Parasite Mind alone is the enemy.

Let us peck at it.

Let us tear it.

Come, let us hunt it down.1

1 Transl. Prema Nandakumar, Subramania Bharati (1968) 116.

One of the most amazing poems of Bharati is Ūḻikkūttu or “The Dance of Doom” which I quote here in a good though not quite equivalent (partial) translation by Prema Nandakumar (op. cit. 86).

As the worlds mightily clash

And crash in resounding thunder,

As blood-dripping demon-spirits

Sing in glee amid the general ruin,

To the beat and the tune

Leapest thou, Mother, in dance ecstatic

Dread Mahakali!

Chamundi! Gangali!

Mother, Mother,

Thou hast drawn me

To see thee dance!

When the demon-hosts clash

Hitting head against head,

When the knocking and breaking

Beat rhythmic time,

When the sparks from your eyes

Reach the ends of the earth,

Then is the doomed hour

Of universal death!

When Time and the three worlds

Have been cast in a ruinous heap,

When the frenzy has ceased

And a lone splendour has wakened,

Then auspicious Siva appears

To quench thy terrible thirst.

Now thou smilest and treadst with him

The blissful Dance of Life!

After Bharati, it was the versatile Putumaippitan (1906-1948) who deviated from traditional poetry; he did not live long enough to mature into a great poet, and Putumaippittaṉ the short-story writer is no doubt more successful than Putumaippittaṉ the poet. A direct line leads from him to T. M. C. Raghunathan who wrote a few very promising poems, but has been lately rather unproductive. K. P. Rajagopalan (1902-1944) died too young to exert any lasting influence on the present developments. There is, however, one great man who has carried on the fire of the Thirties to the post-war period. This man is N. Pichamurti (Piccamürtti, b. 1900). He admits that he was drawn to modern poetic forms only after reading Walt Whitman. His best-known poem Kāṭṭuvāttu (“Wild duck”) was probably one of the decisive turning-points in the development of modern Tamil poetry.

The year 1959 may be considered as the real critical moment in these developments. In this year, C. S. Chellappa (b. 1912), himself a good prose-writer and poet, and probably the most unorthox and modern-oriented literary critic, founded his review Eḻuttu, “Writing”, which opened its pages for anything new and truly creative. The results of the new ferment were visible in a path-breaking and all-important slender collection entitled Putukkuralkaḷ, “New Voices” (Ezhutthu Prachuram, Madras, 1962) which, besides five poems by Pichamurti and Rajagopalan, contains poems composed only between 1959-1962. This volume—apart from 63 poems by 24 poets (a selection made out of about 200 pieces published on the pages of Eḻuttu)—contained also a very important introduction written by C. S. Chellappa.

In addition to Pichamurti’s “Wild duck”, it is probably his Pettikkatai Naraṇan (“Petty shopkeeper Nāraṇaṉ”) which is Pichamurti’s best-known poem. It is a poem about the fall of modern man about a mock-hero, even an anti-hero—and the disintegration of traditional values.

The stork

inside me

… pecks;

I go

rashly open

a

ration shop.2

…..

What is a ration shop

Set up to

Sell

Rice pure like stars

Like faultless pearls?

A sieve?

A winnowing field?

A rice-mill?

Or the woman

Who levels the floor?

There are

Three hundred people

Waiting

Before I even

Unpack

The sack

Where is the place to sift?

Where is the place to winnow?

Where is the time

To be generous and

Polite?

—

(Transl. K. Zvelebil)

2 Transl. S. Gopalie.

C. S. Chellappa’s anthology contains Pichamurti’s poem Pūkkāri (“The flower-girl”) which shows a mature poet who has got rid of foreign influences. Below are given a few verses from parts 2 and 4 of this beautiful poem:

In the darkness of rain

In the streets

No bird

Not even a fly

flying,

The clouds

Grew heavy,

The fish of rain

Jumped.

Laughing lightning

Set clouds afire.

Beautiful women,

Frightened and trembling,

Assembled near the fire

Embracing its warmth.

The beginning of part 4 is a terrible vision of the modern, war-ridden world:

The trident arose

And the universe shook.

And all the world

Turned

Into a

Tent.

Everywhere in the cities

Poisonous smoke.

And all over the skies

Steel wings of weapons

Everywhere in the streets

Mountains of corpses.

—

(Transl. K. Zvelebil)

The young authors whose poems were published in Chellappa’s anthology wanted to dissociate themselves from the stock phrases and the stock content, as well as from the “formulas” prescribing traditional forms. They refused the explicativeness and verbosity of the old, especially medieval poetry (and in this respect, their “modernity” is a return to the unsurpassed and perfect terseness and brevity of the early classical poetry). Chellappa sees them as bearers of a revolt (puraṭci) of a new, different generation. If there is indeed a break with the past, if there is a clash between “tradition” and “modernity” in contemporary Tamil culture, it takes place in the writings of these “new poets”. The first of the “revolting” poems was probably Sundara Ramaswamy’s The nails of your hand:

Cut and throw off your nails—they gather dirt.

Cut and throw off your nails—they gather dirt.

The whole world outside is a heap of dirt.

Why then should nail-corners be so fit for dirt ?

“I may scratch, say I may,

I may scratch—my enemy?”

You may scratch, you may tear apart

In a soothing embrace

The left arm

Of the lovely-eyed

Will drip

Blood

Cut and throw off the nails of your right hand

Or else

Forget the joys of married life

Blood

oozes out

from the tender thighs

of that darling child

whom you lift and carry

on your hip

Cut and throw off the nails of your left hand

Or else

Don’t ever more carry that child

Cut and throw off your nails-they gather dirt.

Cut and throw off your nails-they gather dirt.

“I may dig out, say I may,

I may dig out the wax from my ears?”

You may dig out the dirt

You may dig out the dirt

There is a place for each and every filth

The place may change

And the filth move to the guts

And go and mix with blood

With your blood

Cut and throw off your nails-they gather dirt.

Cut and throw off your nails-they gather dirt.

—

(Transl. K. Zvelebil)

According to Chellappa (New Voices, Introd. p. 10), the poem caused a furore among the readers. Most of them were shocked and disgusted.

Another important poem is C. Mani’s (Maṇi) Narakam (“Hell”), published first in Eḻuttu 43. It is a true milestone in modern Tamil poetry. The minor theme—of the unfulfilled relationship between man and woman—is set within the major theme of corruption in the city (nakaram). Mani’s imagery is extremely effective; his technique is influenced by T. S. Eliot. Hyperbolic abbreviation and powerful phantasy can do without much rhetoric; raw naturalism and surrealism blend in Mani’s poetry. As Chellappa says, when reading the poem one gets the feeling of witnessing a movie, “a panavision movie with stereophonic sound track”.3 The poem has 334 lines.

3 S. Gopalie, “New bearings in Tamil poetry”, The Overseas Hindustan Times, July 26, 1969.

“Like a dog poisoned by hunger / one roams about through endless streets” of the hellish city. The city of Madras. Mani describes the Marina; there are the women, whose “handfuls of tresses become stars in the southern wind, and the light of the eyes are all rainbows in the skies, and all their open lips become split hearts”. There, “in the sand wounded by feet / and in the minds wounded by eyes / there are many scars …”

Then follows (87-100) the well-known passage of Tamilnad of today:

Tamiḻakam is neither in the East

Nor quite in the West.

She placed the pan on the stove

But she refused to cook.

Famine and loss

Are the result.

She does not move foreward,

She does not go back.

The present is hanging in the middle.

Hardened tradition and

Settled belief

Locked from inside

Refuse to give a hand

To cut the knot.

What should one do?”

—

(Transl. K. Zvelebil)

The poem’s basic note is pessimistic, full of frustration, even cynical (152-161):

“One day:

Unable to bear

Many-coloured sounds

Intonations of old tales

Sweet invitations of darkness

Age?

Twenty seven

Married?

Not yet

Whatever

I would add

Would it be

Any use?”

—

(Transl. K. Zvelebil)

The frustration and the unfulfilled man-woman relationship finds powerful expression in lines 285-300:

“Anger raised at deaf eyes

With the hard pressure

Of a forefinger

He dragged

The weighted cart

Try harder bullock

He said

Stumbling Stuttering

Falling on the bed

When she

Sleep’s beauty

Sulked away.

In the blazing sun

Wriggling boneless

This way and that

Struggling dazed

As all women of the world

Turned witches

Feeding fury

Awakened to life

In the bewildered moment

Spent Arose Alive

Hell

Vast Hell”.

—

(Transl. S. Kokilam)

Dharmu Sivaramu from Ceylon with his surrealistic sensitivity and expression has a strong sense of form and an intimate feeling for nature. His poems are not as direct as Mani’s, but his imagery is rather striking.

Daybreak

On the skin of the Earth

Spreading freckles of beauty

Sun copulated

Spreading sperm

Breaking into beams

Blossoms unfold

Gangrenous worms

Gorge on wings of darkness

Birds bustle

In the wings of light

—

(Transl. K. Zvelebil)

Lightning

The stretching beak

of the bird of skies

A look thrown

on the Earth by the Sun

Streams of nectar

pouring into oceans

Red sceptre

in god’s grip

—

(Transl. K. Zvelebil)

Throwing stones

Why do waves

called yesterday and tomorrow

wallow and swell

in the pond of time?

Because drops of stones called today

are flung at it.

—

(Transl. K. Zvelebil)

Speech

Listen, beauty speaks

Tender fleshed lips

Sparkling of blood

Slyly inviting

Looks

Youth’s freshness like a

Drum

Beats at your eardrums

Against the walls

of flower-petals

Echoes of humming

bees die

Against the curtain of

Kisses

Speech dies

But blood speaks

Silence reverberates

—

(Transl. S. Kokilam)

T. K. Duraiswami (Turaisvāmi) is what Chellappa calles an intellectual poet. Here is one of his prose-poems, entitled ‘There is nobody who would not know’.

“There is no one who would not know the house lizard which, clinging to the wall, like a dead crocodile, clad in dull brownish colour, will suddenly jump from its lurking-place without a sound at its prey.

There is no one who would not know the spider which has made its web from its spittle and, spreading its eight legs, watches motionless in the middle of the cobweb for the unfortunate butterflies and beetles which get entangled in the trap.

There is nobody who would not know that there are flies which swarm and buzz like those prophets of equality, not discriminating between cleanness and filth, like those demons betraying knowledge, with small wings, warm-like bodies, purulent red heads, all covered with eyes.

We also know this heap of big black ants, who organize themselves in multitudes, bearing that preposterous dark red colour, and, like some hideous spreading pools, brush aside and choke those who stand in their way, hastening next minute to death”.

(Transl. K. Zvelebil)

Probably the most talented and, at the same time, the most conscious craftsman of all the “new poets” is T. S. Venugopalan. However, according to some, S. Vaitheeswaran is the best of all the lot.

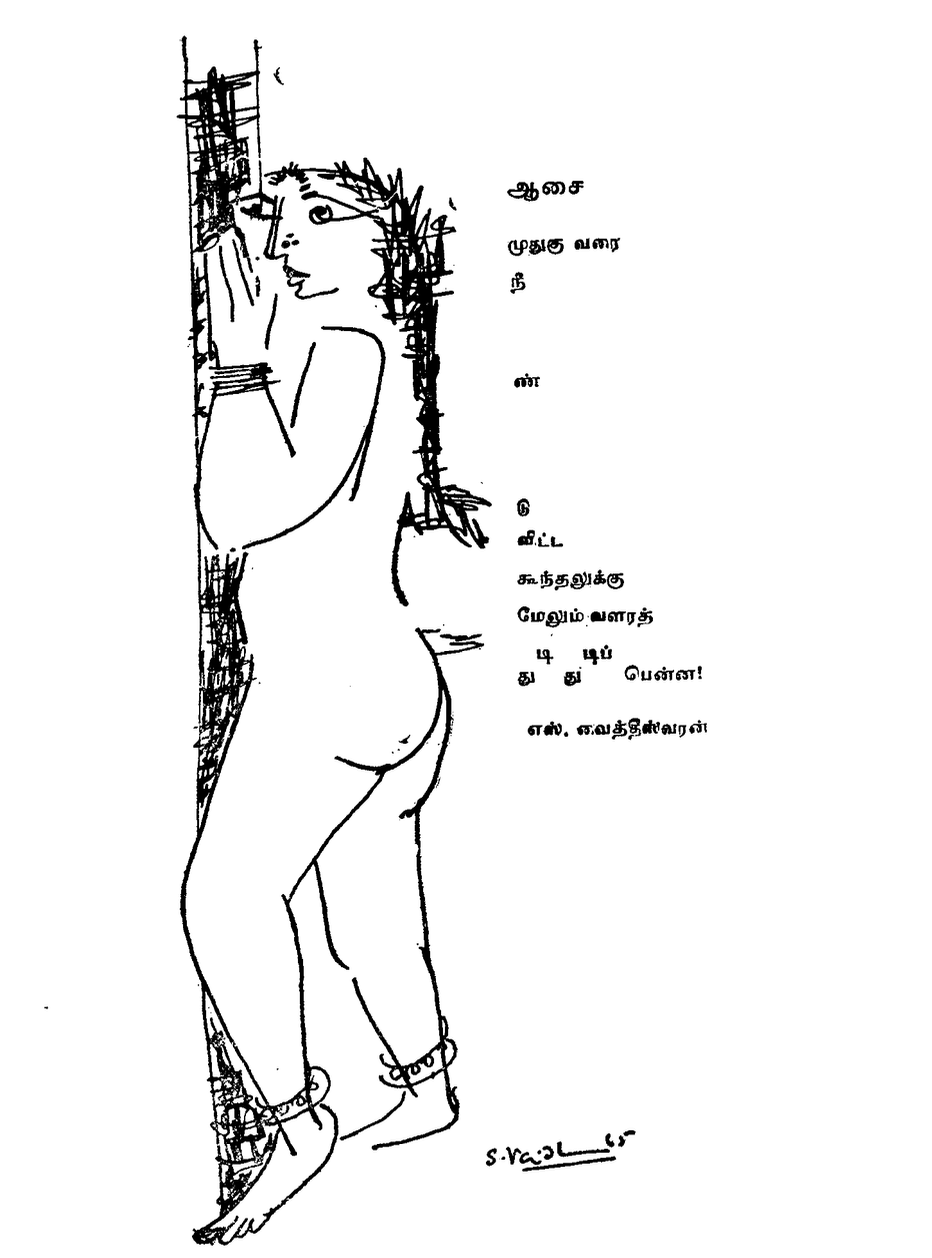

S. Vaitheeswaran’s experimental trifle (published in Naṭai, 1969,4) is reproduced on the following page (Figure 20.2). The text says:

DESIRE

What a throbbing

rising and growing

along the

long

lo

ose

hair

reaching

the rounded back!

What follows is a short random reader of their poetry which hopefully needs no comment.

S. Vaitheeswaran

Fireflies

In every nightly street

sprout trees of lights,

fruits of flames above

shedding milk on the ground.

Furiously flapping

fireflies in futile strain

rise in the air and fail and fall.

In demi-shadows

jasmin-mouths smell and wed,

lightnings of teeth

and women’s hair shine,

and with love’s caprice

many pairs of eyes

barter and clash

and become

fireflies.

(Transl. K. Zvelebil)

The same poet’s “Nature” is, in the original, a very powerful poem; I feel that the translation of this poem in particular is very difficult, and that it does not do justice to the Tamil version.

The Sun reached the sea

but

Time dragged it ashore.

Fragment of a cloud

floated

as it wiped the body;

cold conquered

with spreading body

one eye winking and shut

Fire rained on Earth

as earth’s skin caught

Fire.

“Why a swing

for him who scorches the body?

Why a festival?

Why a golden gown

for him who tortures life?”

cursed the Earth.

Suffering fell the Sun:

“What can I do for nature?”

It trembled

With its hands

tore its heart

Knocked its head

against mountains

Shrieked out:

“If body burns body

must soul hate soul?

If water abates fire

am I the sea’s enemy?

See!” It said

as it dived into the sea:

The sea enwrapped the fire.

—

(Transl. S. Kokilam)

The next poem, one of the best ever written in modern Tamil poetry, was translated very well by S. Gopalie.

Thorn

“Shoe polish … repair”,

shouted the boy.

I flexed my leg

showed him

(the heel);

Scoundrel—He

Cut open my so(u)le

took out the thorn,

took to his heels,

not taking money.

…. now,

my grief keeps raging:

the thorn removed from the heel,

has moved into my soul

for good.

Vaitheeswaran is also capable of very short epigrammatic poetic jokes like the following two pieces:

Flesh-cart

In the flesh-cart

dragged by man

the tugging horse

said: “Hi, hi, hi!”

Fear

In fear of darkness

I closed the door of my eye-lids.

“Nruff!” said the

New darkness inside.

T. S. Venugopalan is considered by some the most original and the most gifted of all ‘new poets’, the one who “has everything in him to become not only a great modern poet but a people’s poet as well”. When reading his poems, one can feel how very carefully he writes—the detachment and impersonality of some of his poems remind the reader of the great achievements of classical Tamil poetry of the ‘Caṅkam’ age. Here is how he sees the Moon, a constant companion of poets in India.

They call her Princess.

I haven’t seen her

For many many days!

Now I met her.

It was

When she fell

Pitifully

Into the well of your house

And you called out

To save her

And stretched out your hand.

Then

Today in the night

In the good water well of my garden

Oh me!

Slipping out of her garments

She bent her body

And lured me

With her winking eyes …

Shshsh …. ocking!

………

Back with your outstretched hand!

Come back!

No … Wait.

Take a stone.

And before Jesus comes

Throw and strike!

Let the hands of waves

Sweep away

That vile vicious glee

Off the Moon’s face.

………

Cut off and throw away

The hands outstretched

To touch her and to lift

Her up

The leprosy of lust

Sticky and glutionous

Will corrupt

Your form!

……..

Shameless harlot

Look at her

The Moon

—

(Transl. K. Zvelebil)

In another poem, he addresses Śiva, the dancer of doom and destruction.

What sense

You burst

With struggling curves

Your belly turns

Folding in

Waves

Why such burning fury?

What silent weight was

Born

In your soul and then

Grew and crushed?

Burning sighs

Leapt across the larynx

And gurgled. Why?

Through the corners of your mouth

Drips

The juice of the betel-leaf

And burns tender shoots

And blackens the earth. Why?

Toothless hag’s abuse

A little child’s hiccups

Why did they become your speech?

A gopuram

And a few palaces

Slid scattered and died:

And you

Though feeling the flow of time

What reason you give

For burning poor huts

Turning them

Into dust?

What sense has

Your

Demoniac dance?

—

(Transl. S. Kokilam)

As an instance of his symbolic, “metaphysical” poetry, here is a piece called Ňāṉam (“Enlightenment, Knowledge, Wisdom”).

The doors of the porch, frame;

Wind breaks.

The dust of the streets

Adheres

To these.

White ants

Build

Sand houses.

That day

I cleaned,

Painted,

A new lock

I fixed.

Ass of time

Turned ant

Even today

In my

hand

A bucket of water,

Pail of paint,

Rags, broomstick;

Work of dharma

Service of charity

Never ends.

If it ends

There is no world!

—

(Transl. S. Kokilam)

Literary experience

Two ways

To be told

With thought

Without thinking!

A swirl or

A blind-fold:

For both

The meaning

Is expressed by the poet!

Pictured by the artist!

The one who gazed

You and I only

(For shame)

Are the readers’ crowd!

—

(Transl. S. Kokilam)

Finally, a poem on sterility, in a very able translation into English by S. Gopalie.

I heard a cry

from the next door.

Sweets followed suit.

The bride

in her maiden

nuptial night

grabbed her

lower abdomen.

Can you conquer time

tearing the calender?

Why wish for ergot

without the wait

and pain attending upon it?

No use moping and mooning,

If you don’t care to see

the genuine from the fake.

Not all that sprouts

is great.

And an epigrammatic poem by T. S. Venugopalan, entitled

Old greatness

Curried mango-seed

Spoke of noble ancestry;

I planted and waited;

The vast tree

and its fruits

turned out a shadow!

Wriggled out

only

a worm!

—

(Transl. S. Kokilam)

While Vaitheeswaran is more emotional, more lyrical, more personal, more traditional, T. S. Venugopalan is more intellectual, more reflexive, impersonal, cooler; while Vaitheeswaran is more colourful, economical and yet rich in words, and more individual and self-centred, Venugopalan is more disciplined, sharper, less individual and more open towards society and contemporary problems. However, it is very difficult really to say—and probably it is quite unnecessary and even naive to try to—who is the better of the two. What is important is the fact that, unlike fifteen or even ten years ago, contemporary Tamil writing has at least two poets who are first-rate and full of growth and promise.

Doing away with traditional poetic forms, and trying their hand at vers libre, “prose-poetry” (vacaṉak kavitai) and other formal experiments was and still is part of the credo of the “new poets”; cf. Eḻuttu 61 where a “new poet” says

“A poem tied by prosody

is like the Kāviri tied by dams”.

However, it seems4 that even the most “rebellious” formal experiments of the “new poets” may somehow and to some extent be reconciled with the literary marapu or tradition: thus, e.g., the so-called centoṭai, i.e. verses without etukai “rhyme (initial)” and mōnai “alliteration”, may be considered a kind of vers libre; or, rather, the free-verse experiments are nothing but a kind of traditional centoṭai. On the other hand, the basic properties of classical and traditional poetry and prosody are used frequently even by the most “rebellious” “new poets” simply because the features are inherently connected with the very structure and nature of Tamil phonology and syllabification, just like the notion of acai “fundamental metric unit” is inherently connected with the very rhythm of Tamil speech. Thus, e.g., if we consider a poem like D. Sivaramu’s Miṉṉal (Lightning) we see a rather firm rhythmic structure in terms of the basic, “traditional” prosodic units, acai and cīr “feet” (the poem being limited to the use of the socalled iyaṟcīr “natural feet” of two acai each). We also unmistakenly hear the initial alliteration (mōnai) of (ka-), placed most regularly at the beginning of each first feet of the four distichs.

4 Cf. a very interesting essay on classical and modern prosody by Selvam (Celvam) in Naṭai, 3, April 1969.

| kakaṉap paṟavai | = - = - |

| nīṭṭum alaku | - - = - |

| katirōṉ nilattil | = - = - |

| eṟiyum pārvai | = - - - |

| kataluḷ vaḻiyum | = - = - |

| amirtat tārai | = - - - |

| kaṭavuḷ uṉṟum | = - - - |

| ceṅkōl | - - |

Even very daring instances like

| ki | in |

| уū | the |

| vi | que |

| lē | ue |

| orē kūṭṭam | one crowd |

| — | |

| (Eḻuttu 91) |

may be reconciled with tradition: according to Mr. Selvam, the author of the cited essay on prosody (see ftn. 1, 331), such formal device was well-known as a kind of cittirakkavi “picture-poem” (cf. taṇṭiyalaṅkāram 68).

We are prepared to agree with this opinion to the extent that the “new poetry” is, indeed, reconcilable with Tamil tradition5 as far as the basic, “low-level” structural elements—i.e. the acai and the cir (foot), partly also the line (aṭi)—are concerned. The traditional stanzaic structures of higher levels (pā, iṉam) are, however, not adhered to by the “new poets”. Indeed, there is one very fundamental ‘high-level’ feature which means a definitive break with tradition as far as the “new poetry” is concerned. Since the early bardic poetry of the classical age up to the poems by Bharati, Tamil poetry has been sung or at least scanned in a sing-song manner. In some epochs and with some kinds of poetic composition, music and literature, singing and poetry became so intimately connected that the one does have hardly any existing without the other (as is the case, e.g., with the patikams of the classical bhakti poets, or with Aruṇakiri’s songs). The “new poetry”, however, is meant to be read and/or recited, but not sung.

5 We should not forget, though, that the striving after reconciliation with tradition (marapu) is a very typical pan-Indian tendency, and has been so for ages.

6 Tamil literature has known empty, unproductive and repetitive formalism for centuries. But perhaps none of the “new poets” is one of the sterile formalists.

Another novelty of this modern and avantgarde poetry lies in the new, surprisingly effective and forcible use of the traditional material; in the new, and hence different, and most powerful, utilization and application of the basic prosodic and formal properties of Tamil poetry, not in denying and destroying them. Finally, the “new poets” strive seriously after an organic and intimate relation between form and meaning, after the unity of meaning (poruḷ) and form (uru, uruvu, uruvam). The “new poets” are in their absolute majority no empty formalists.6 L’art pour l’artism is not their credo, though some of the very contemporary poets, like V. Mali, go rather far in their formal experiments.

To close this chapter, I shall quote a few poems by four very recent young poets, Hari Sreenivasan, Tuṟai Seenisami, V. Mali and Shanmugam Subbiah. The choice is quite casual. The translations are mine. Let us say that these four stand for a number of other equally or probably even more important names, most of which indicate that modern Tamil literature has been finally lashed out of its lethargy, apathy and sterility.

Hari Sreenivasan

Weep

Weep Weep Weep

Only if you weep you’ll get milk

But

Don’t forget

There’s salt in tears

Beware

The milk

Will curdle

Turai Seenisami

Unquenchable hunger

Like bodiless souls

Moving about

The overwhelming peace

Of pitch darkness

Makes me dazed

There is no moon

Upon the blue cake

Dots of stars are

Suger-coated drops

I became hungry

Opening the mouth of sight

I gorged the whole night

But I am still hungry

V. Mali

Question. Answer?

For many days one could watch

hips and shins dancing.

Everyone admired it with respect.

One day one could see

thighs and nipples dance.

Everyone rose in boiling wrath.

She asked:

How is it

that this

is

more obscene than

that?

Mini Age

Mini age is

born.

Big

man’s

might vanished.

NOW it is

mini peoples’ time.

Man I forgot

minimen’s deeds praised. Hear

my crooked speech.

My! When you ask how I k

NOW I am a

mini poet.

How’s…?

Two sadhus were

talking.

My god is a treasure!

He loves the poor and the rich alike.

How’s your god?

My god?

He is the Lord God of the Ecran7

Who loves the screen-stars.

—

(Transl. K. Zvelebil)

7 A fine pun in the original: tirainaṭ cattiraṅkaḷ virumpum / tiraippatik kaṭavuḷ tān.

Sh. Subbiah

To Westerners

We are not like you

on the one hand

who

wield a way to live

and on the other

dig out a grave to die.

But we

we do not long for life

we do not dare to die.

We are not

like you.

We are we—

lifelessly alive,

dying undying.

—

(Transl. K. Zvelebil)

Lullaby

Why do you weep

when no one beat you?

Is it

because you hate me

that I tried

hard

that you should not be born?

Why do you laugh

when no one made you?

Is it

because you deceived me

by the joke of being born

forlorn?

—

(Transl. K. Zvelebil)

It is a decade now since the “new poets” began their conscious attempts to evolve a new Tamil idiom, to write, uninhibitedly, about unconventional or even prohibitive themes, to get rid of fashionable foreign influences and to create a truly modern Tamil poetry. They have not made any impact on the general public. They are almost unnoticed by the common reader; they are almost hated by the orthodox traditionalists; they are entirely ignored by most professors of Tamil and Tamil literature. And yet, as S. Gopalie rightly says,8 “compared to the growth in other branches in Tamil literature, modern Tamil poetry has taken giant strides in recent years and has come to stay.”

8 S. Gopalie, “New bearings in Tamil poetry”, The Overseas Hindustan Times, July 26, 1969.